{{currentView.title}}

November 24, 2025

Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in West Africa Interactive Map and Campaign Analysis

Contributor: Christopher Dayton and Olufemi Omotayo

To receive regular analysis of the Salafi-jihadi insurgencies in West Africa, subscribe to the weekly Africa File here. Follow CTP on X, LinkedIn, and BlueSky.

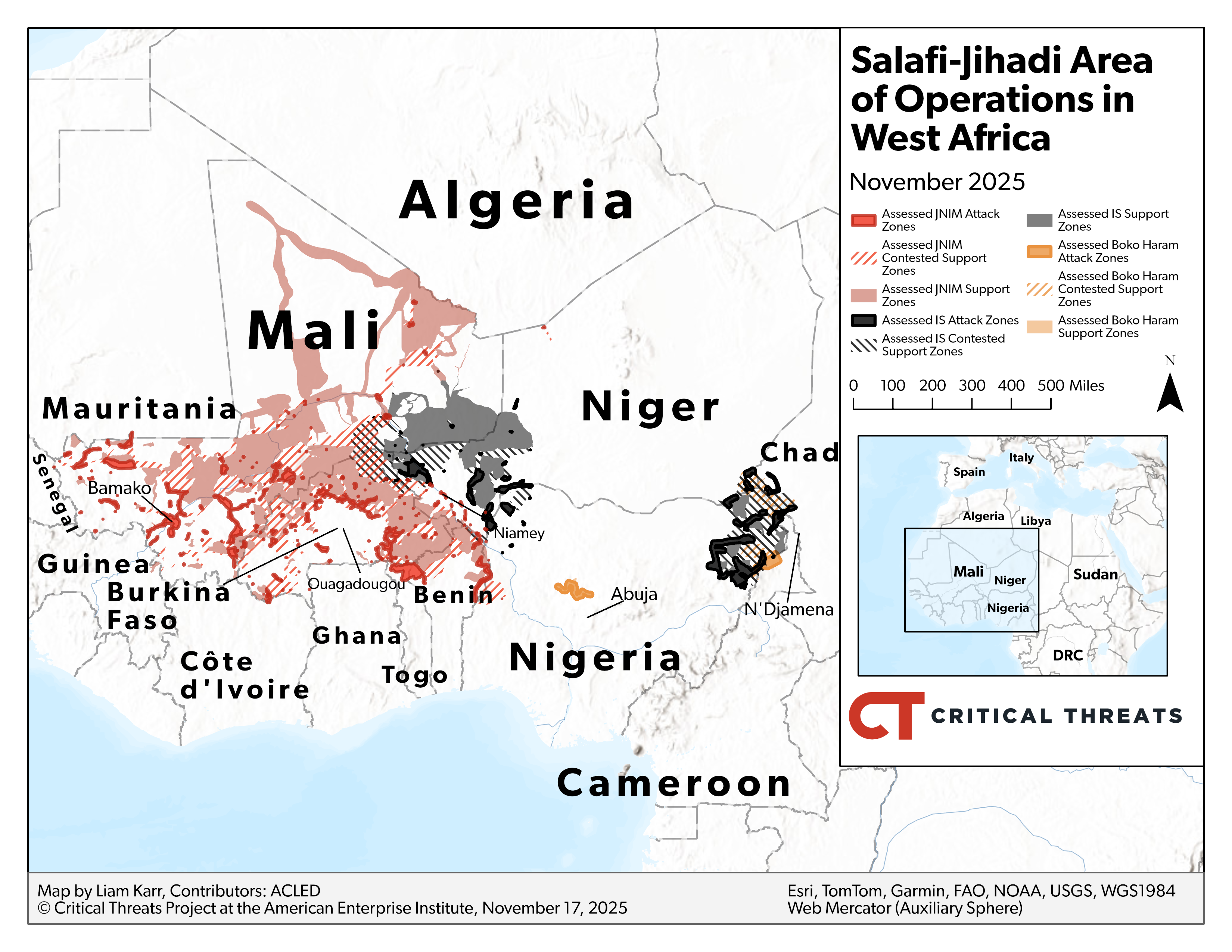

VIEW THE INTERACTIVE VERSION OF THE MAP HERE.

West Africa has become the epicenter of global Salafi-jihadi activity. Four of the top six countries in the Global Terrorism Index are found in the region—with Burkina Faso topping the list and Mali, Niger, and Nigeria in spots four through six, respectively.[1] Al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates are expanding rapidly across the region, taking advantage of long-running grievances, state incapacity, and ineffective counterinsurgency partnerships. In the Sahel in particular, al Qaeda’s affiliate is encircling Mali’s national capital and bringing the insurgency to the country’s most economically and politically sensitive areas, threatening to cripple the national economy and government. The predominant groups in the Sahel are Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), which is an affiliate of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP), previously known as Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. IS West Africa Province (ISWAP) and the infamous Boko Haram, formally called Jama’at Ahl al Sunna lil Da’wa wal Jihad (JAS), are the major players in the Lake Chad Basin.

Long-standing loose ties between the Sahelian-based and Lake Chad–based groups have grown significantly in the last five years. Both JNIM and ISSP have established a foothold in northwestern Nigeria since 2020 and operationalized these cells since 2024. ISSP and ISWAP have increased collaboration through the ISWAP-based IS West Africa regional office, Maktab al Furqan.[2] These ties have resulted in ISWAP sending fuel, weapons, and other equipment, as well as fighters and trainers, to support ISSP activity in Burkina Faso and Mali. IS has also shown a clear intent to use ISSP and its trans-Saharan networks to support attack cells in North Africa and Europe and support the movement of foreign fighters to West Africa.[3]

Table of Contents

Figure 1. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr and Christopher Dayton; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

Map updated November 2025

Attack Zone: An area where units conduct offensive maneuvers.

Contested Support Zone: An area where multiple groups conduct offensive and defensive maneuvers. A group may be able to conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces but has inconsistent access to local populations and key terrain.

Support Zone: An area where a group is not subject to significant enemy action and can conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces.

Control Zone: An area where a group exerts largely uncontested physical or psychological pressure to ensure that individuals or groups respond as directed. Control zones are a subset of support zones.

Methodology Note: The Critical Threats Project adapts its mapping definitions for insurgencies from US military doctrine, including US Army FM 7-100.1 Opposing Force Operations. Our maps are assessments and reflect analysts’ judgment based on current and historical open-source information on security incidents, political and governance activity, and population and geographic factors. Please contact us for more information on specific maps.

Prior Versions

Sahel

Figure 2. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Background: The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Sahel

The Salafi-jihadi movement in the Sahel has roots in the Algerian Salafi-jihadi movement of the early 2000s, from which AQIM emerged. AQIM gained influence in the Sahel throughout the 2000s, eventually infiltrating and co-opting a 2012 rebellion driven by long-running ethnic grievances in partnership with Ansar al Din, which is based in northern Mali.[4] A French-led response rolled back AQIM and its allies’ conquest of northern Mali in 2013.[5] Thousands of French and UN troops remained in the Sahel over the following decade in an effort to stem the resurgence of these insurgents.[6]

Four Salafi-jihadi groups merged to create JNIM in 2017: AQIM’s Sahara Emirate, Ansar al Din, the Macina Liberation Front, and al Murabitoun.[7] A fifth group, based in Burkina Faso, Ansar al Islam, is a de facto member of the group despite not formally being part of the merger.[8] The group maintains a top-down hierarchy that orients its strategy and coordinates between the different subgroups.[9] However, it also gives the subgroups significant operational freedom to best exploit their local contexts—such as appealing to local ethnic constituencies.[10] JNIM has embedded itself in local governance structures and implemented various forms of shadow governance through local agreements across the Sahel.[11] JNIM is most active in Mali and Burkina Faso, though it is present in Niger and expanding into the northern Gulf of Guinea states.

ISSP formed when a faction of an AQIM splinter group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2015.[12] The Islamic State did not recognize ISSP as a formal province until March 2022.[13] ISSP is most active in the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. ISSP and JNIM, unlike other al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates globally, did not initially fight each other.[14] However, the two groups have engaged in phases of conflict since 2020.[15] JNIM and French military pressure substantially weakened ISSP in 2020, but ISSP has significantly strengthened since the departure of French forces in 2022.[16]

JNIM and to a lesser extent ISSP are gradually expanding outward, toward neighboring coastal states.[17] Overlapping issues—including climate change, poor governance, and communal tensions—are enabling the Salafi-jihadi movement to embed in local communities.[18]

Campaign and Map Updates

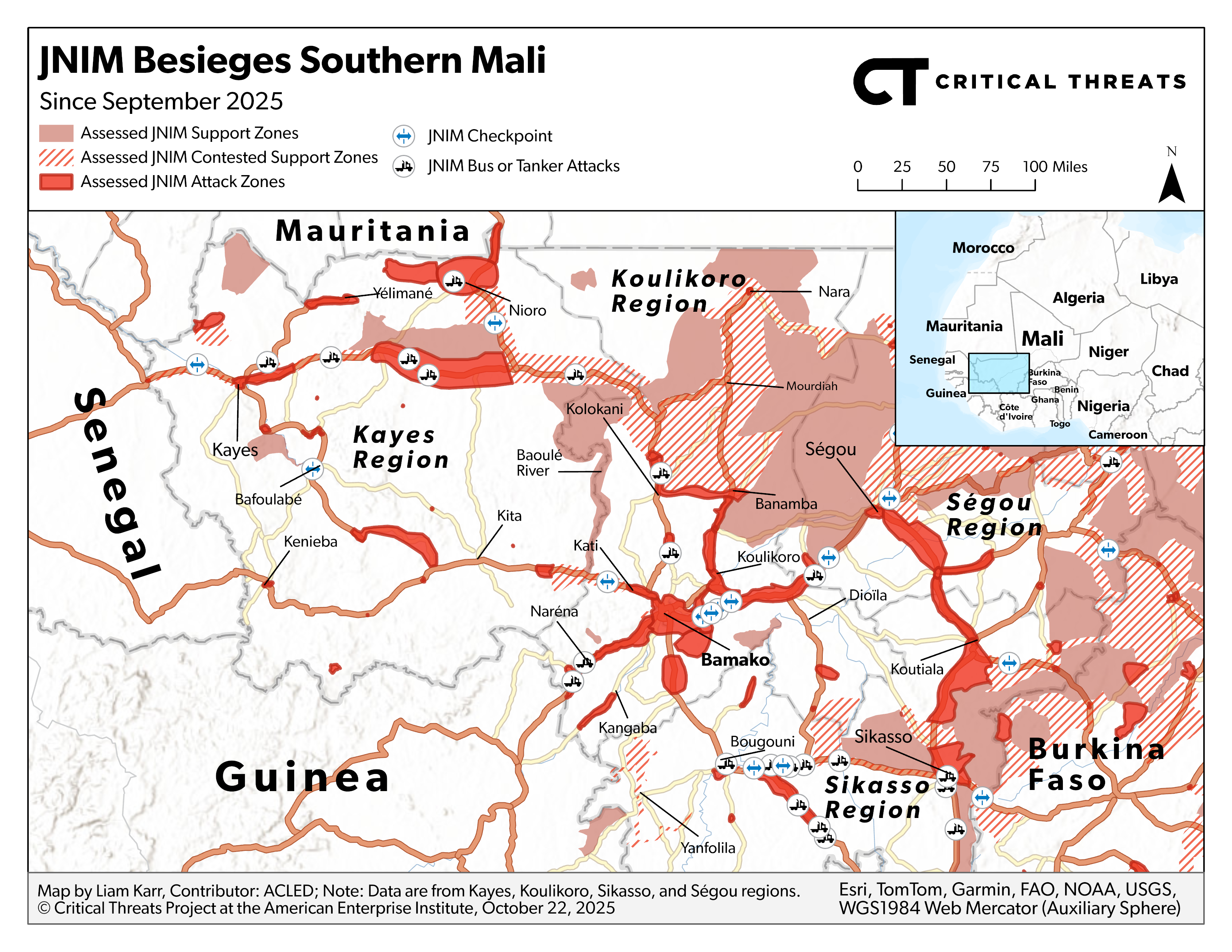

JNIM Blockade

JNIM has imposed a blockade on central and southern Mali. JNIM declared a blockade on Kayes and Nioro—key cities in western Mali—in July and began enforcing its fuel blockade across the southern half of Mali more broadly on September 3.[19] The blockade initially targeted supply corridors from Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, which carry nearly 95 percent of Malian petroleum imports, but was expanded on November 1 to include Bamako’s eastern supply corridor from Niger via central Mali.[20] JNIM has destroyed more than 300 tankers since the start of its blockade.[21]

JNIM initially launched its blockade to coerce the junta into lifting its ban on fuel sales in rural villages across Mali.[22] The fuel smuggling corridors that run through these villages were critical to JNIM’s military operations and efforts to control local economic activity in Mali. The corridors stretch from Mauritania to Nigeria and involve an informal network of independent smugglers.[23] JNIM exploits these networks across the Sahel by taxing smugglers, securing unregulated supply chains, and building legitimacy among the communities in which it operates.[24]

The blockade has begun to cripple the national economy, undermining popular support for the junta, but the junta has gradually adapted to JNIM’s tactics. The fuel shortage has caused fuel prices in some areas to more than double, closed gas stations across Mali, and left citizens waiting for hours in line at the stations still operable.[25] The limited fuel that is safely transported to Bamako is mostly diverted to the Malian army and the state-owned Énergie du Mali, forcing many businesses and institutions to remain closed.[26] The Malian junta closed schools and universities nationwide, from October 27 to November 11, after school faculty could not travel due to fuel shortages.[27] A Malian business owner reported that up to 80 percent of his workforce was absent, causing an 85 percent drop in production.[28] The situation is worse in other parts of the country, with major towns such as Mopti left without power for over a month.[29]

The fuel crisis has eroded relations between the junta and the transportation sector. JNIM has targeted Diarra transport company buses as part of the blockade due to the company frequently transporting Malian security forces.[30] The group explicitly banned the company from operating in a September 3 decree, but lifted the ban on October 17 after the CEO agreed to JNIM’s terms.[31] The Malian army suspended the company’s operations on October 22 due to the agreement, however.[32] Malian officials accused private operators of colluding with JNIM and being responsible for the crisis in mid-October, leading to a brief truckers' union strike before they resumed operations after a public apology from the government on October 20.[33] JNIM said on November 16 that it would consider fuel truck drivers military targets and execute them as part of this effort, threatening to again undermine support for the junta if it is unable to protect Malian truckers.[34]

The junta has begun adapting its convoy protection protocols and fuel procurement strategies to alleviate pressure on the southern half of the country. The junta has successfully transported at least 1,200 tankers to the capital via the Bougouni–Côte d’Ivoire trade corridor and reshuffled the Malian military command since October 27.[35] CTP has previously assessed that increased Malian counterinsurgency pressure and air cover have helped degrade JNIM’s presence along the route. Local media has also reported that Russia agreed to deliver up to 200,000 tons of petroleum and agricultural products to Bamako and is negotiating to provide the junta with technical assistance to secure transport routes.[36]

Figure 3. JNIM Besieges Southern Mali

Note: Data are from Kayes, Koulikoro, Sikasso, and Ségou regions.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

JNIM has leveraged the success of its blockade to opportunistically expand the blockade's objectives to include several shari’a-based governance measures. A JNIM spokesperson announced on October 17 that the blockade on the southern half of Mali would continue until the junta fell or agreed to apply shari’a law nationwide.[37] The declaration accompanied a decree on public transportation requiring women to veil themselves and sit separately from men.[38] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) has since recorded at least six incidents of JNIM militants enforcing this declaration at checkpoints in central and southern Mali.[39]

Western Mali

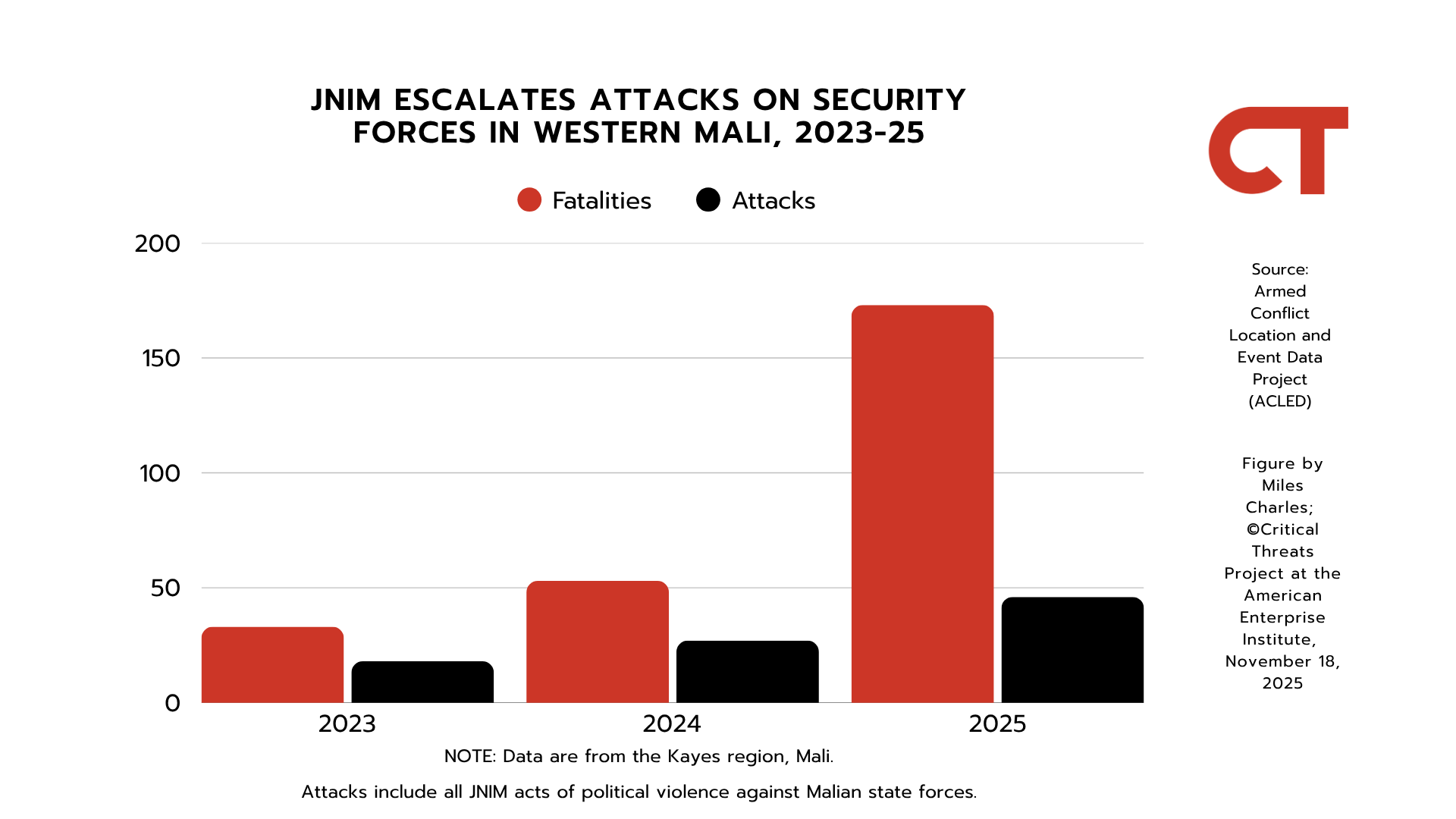

JNIM has expanded the scale and scope of its activity in western Mali, particularly in the second half of 2025, as part of its blockade. JNIM launched a series of attacks targeting eight locations across western Mali on July 1, including Kayes city, the regional capital.[40] JNIM’s assault also targeted border posts along the Senegalese and Mauritanian border.[41] The attacks included the group’s first attack on Kayes city and closest-ever attack to Senegal—less than a mile from the border on the Diboli border post.

JNIM has escalated activity in western Mali in the second half of 2025 more broadly as part of its ongoing blockade. JNIM has attacked security forces in Kayes region more through November 2025 than in the entirety of 2024.[42] More than 70 percent of these attacks occurred after July.[43] JNIM has also escalated attacks on civilians, conducting nearly three times as many attacks on civilians through November 2025 as it did in 2024 and 2023 combined.[44] Roughly 60 percent of these attacks occurred after July.[45]

Figure 4. JNIM Areas of Operation in Western Mali

JNIM could use its growing presence in western Mali to expand rear support zones in Mauritania and Senegal. JNIM activity in the Kayes region has grown more than sevenfold since 2021, and the group has inflicted more than double the number of fatalities through November 2025 than it did from 2023 to 2024 combined.[46] ACLED has recorded a record 10 control indicators across western Mali in 2025, which CTP defines as events that indicate a group is able to exert largely uncontested pressure to ensure individuals or groups respond as directed.[47] The Timbuktu Institute—a Senegalese think tank—reported that the group currently uses supply points in at least four communes and the Baoule forest in Kayes region.[48] The Malian army has already carried out more operations against JNIM in Kayes 2025 than it did in 2023 and 2024 combined, highlighting the seriousness of the threat.[49]

Figure 5. JNIM Escalates Attacks in Western Mali

Note: Data are from Kayes region, Mali. Attacks include all JNIM political violence events against Malian state forces.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data

JNIM may use its strengthened presence to expand rear and cross-border support zones in Mauritania and Senegal. JNIM has already used its presence in Kayes to embed itself in cross-border networks in Mauritania and Senegal.[50] The group is heavily involved in both legal and illicit cross-border economic activity, such as livestock, timber, gold mining, and other smuggling activities.[51] Senegalese forces have already arrested JNIM recruiters attempting to build support cells in Senegal.[52]

Southern Mali

JNIM has expanded and strengthened support zones in the Sikasso region. ACLED recorded a record 45 control and support indicators in Sikasso in 2025, which CTP defines as events that indicate a group is not subject to significant enemy action and can conduct effective logistics and administrative support of forces.[53] The group collected taxes and established checkpoints in 12 key towns and border crossings along the RN7, RN10, RN12, and the Burkina Faso–Mali border in 2025. The group also damaged three separate cell towers 80 miles west of Sikasso, disrupting communication and further isolating rural areas.[54]

Figure 6. JNIM Areas of Operation in Southern Mali

JNIM has likely leveraged these zones to escalate attacks along key roads in the region, supporting its blockade and degrading government control over military ground lines of communication and economic trade arteries. JNIM has attacked within nine miles of the RN7, RN11, and RN12 in more than 90 percent of its attacks. The group has particularly targeted forward operating bases and patrols near these roads, attacking mobile units more often than entrenched positions in 2025.[55] These attacks restrict the movement of troops along the roads, isolating security forces to major towns and enabling the group to strengthen its support zones.

Figure 7. JNIM Escalates Attacks on State Forces in the Sikasso Region, 2023–25

Note: Data are from Sikasso region, Mali. Attacks include all JNIM political violence events against Malian state forces.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

The three roadways are key arteries connecting Bamako to southern Mali, Burkina Faso, and Côte d’Ivoire. JNIM has targeted sections of the roads around Sikasso and Koutiala—the regional capital and a cercle head, respectively—gradually isolating Sikasso from Bamako.[56] The group’s attacks and checkpoints along the Burkinabe-Mali border also influence cross-border commerce between the two countries, an essential economy for border communities.[57] JNIM is known to tax drivers along these border communities and participate in local markets, both buying and stealing goods.[58] The group has separately targeted the trade corridor from Abidjan to Bamako as part of its fuel blockade on the southern half of Mali.[59] The Abijdan–Bamako trade corridor is responsible for more than 10 percent of Malian imports and 57 percent of fuel imports.[60] JNIM has attacked 18 separate fuel tankers or convoys from Côte d’Ivoire.[61]

The group may use strengthened support zones along the border in southern Mali to expand rear support zones in Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea. Al Qaeda–linked militants have attempted to infiltrate Côte d’Ivoire since 2015, and JNIM carried out attacks in northern Côte d’Ivoire in 2020 and 2021.[62] The Ivorian government degraded JNIM’s presence and has so far kept JNIM at bay through a strategy that has combined border security and socioeconomic development, although there are reports that JNIM continues to have some rear support zones along some areas of the Malian border.[63] Côte d’Ivoire is particularly important to the group’s livestock smuggling, serving as a key market.[64] Ivorian police arrested several JNIM militants attempting to set up local cells in 2025, underscoring an effort to expand the group’s presence in the country.[65]

JNIM has also increased its activity along the Mali-Guinea border since 2024. The group recorded its first attack in Mali’s Kenieba and Kangaba cercles near the Guinean border in 2024.[66] CTP assessed in 2024, however, that while northern Guinea could serve as a rear support zone, JNIM would struggle to gain a foothold.[67] Intercommunal tensions that have made communities vulnerable to JNIM recruitment are present in Guinea, but the Fulani community that JNIM has exploited in the Sahel is more politically integrated in Guinea than it is in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.[68]

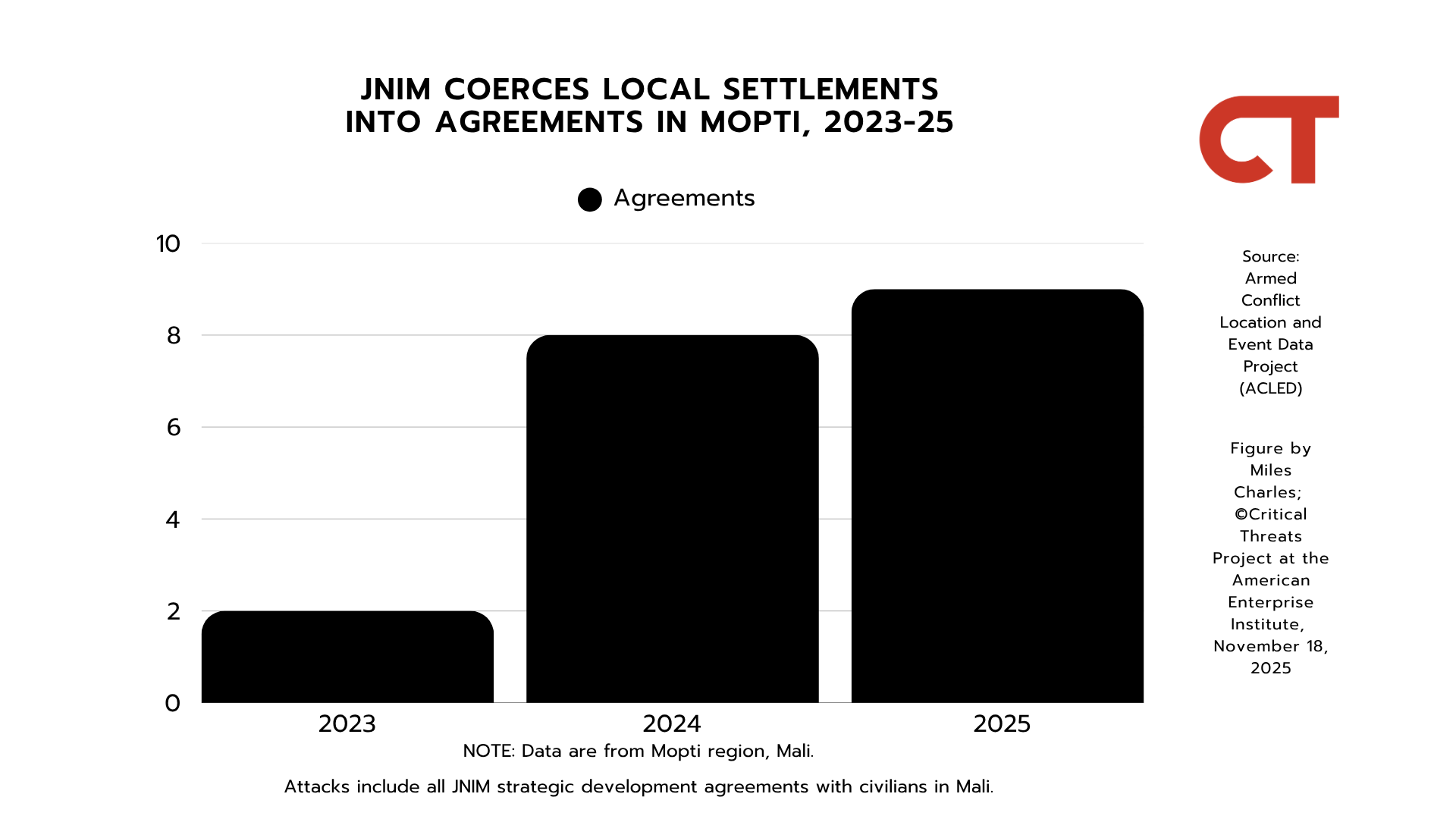

Central Mali

JNIM has conducted fewer attacks in the Mopti region in 2025 as it consolidates control of territory outside government strongholds through local agreements. JNIM reached agreements with several besieged communities in Mopti, with the approval of the Malian junta, in early 2025.[69] JNIM has secured de facto control over several areas through these agreements. The group typically ends its siege in exchange for communities agreeing to pay tax, adhering to JNIM-interpreted shari’ia law, and ceasing support for Malian security forces. The agreements typically involve local militias, which are the main resistance to JNIM in rural areas, but have involved state forces agreeing to confine or reduce their presence in some areas where they remain present.[70]

Figure 8. JNIM Coerces Local Settlements into Agreements in Mopti Region

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

JNIM has leveraged the control it has gained to expand support zones throughout central Mali. JNIM has displaced a record number of villages across central Mali in 2025.[71] The evictions, alongside an increase in Malian air strikes, indicate that the Malian junta is unable to regularly contest ground control in these areas, allowing JNIM to operate without significant enemy action.

Figure 9. JNIM Areas of Operation in Central Mali

JNIM’s growing control in central Mali has strengthened cross-border support zones, which could facilitate subgroup collaboration. JNIM may use strengthened support zones to facilitate cooperation between the Katiba Macina and Ansaroul Islam.[72] Ansaroul Islam operates in the tri-border region of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, while Katiba Macina operates in western Burkina Faso and central, southern, and western Mali. CTP assessed in May that the two affiliates may have collaborated to orchestrate the Djibo attack that killed 200 people.[73] Tuareg fighters, likely from JNIM’s northern Mali–based subgroup Ansar al Din, have been participating in the Katiba Macina–led blockade in southern Mali, indicating that fighters are able to move from northern Mali to southern Mali via the group’s support zones in central Mali.

Tri-Border (Liptako-Gourma) Area

Note: CTP refers to Burkina Faso’s former administrative territories, prior to the Burkinabe government’s administrative reorganization in July 2025, in the following sections. CTP will use Burkina Faso's new administrative territories in future updates as geospatial information of the new territories allows.

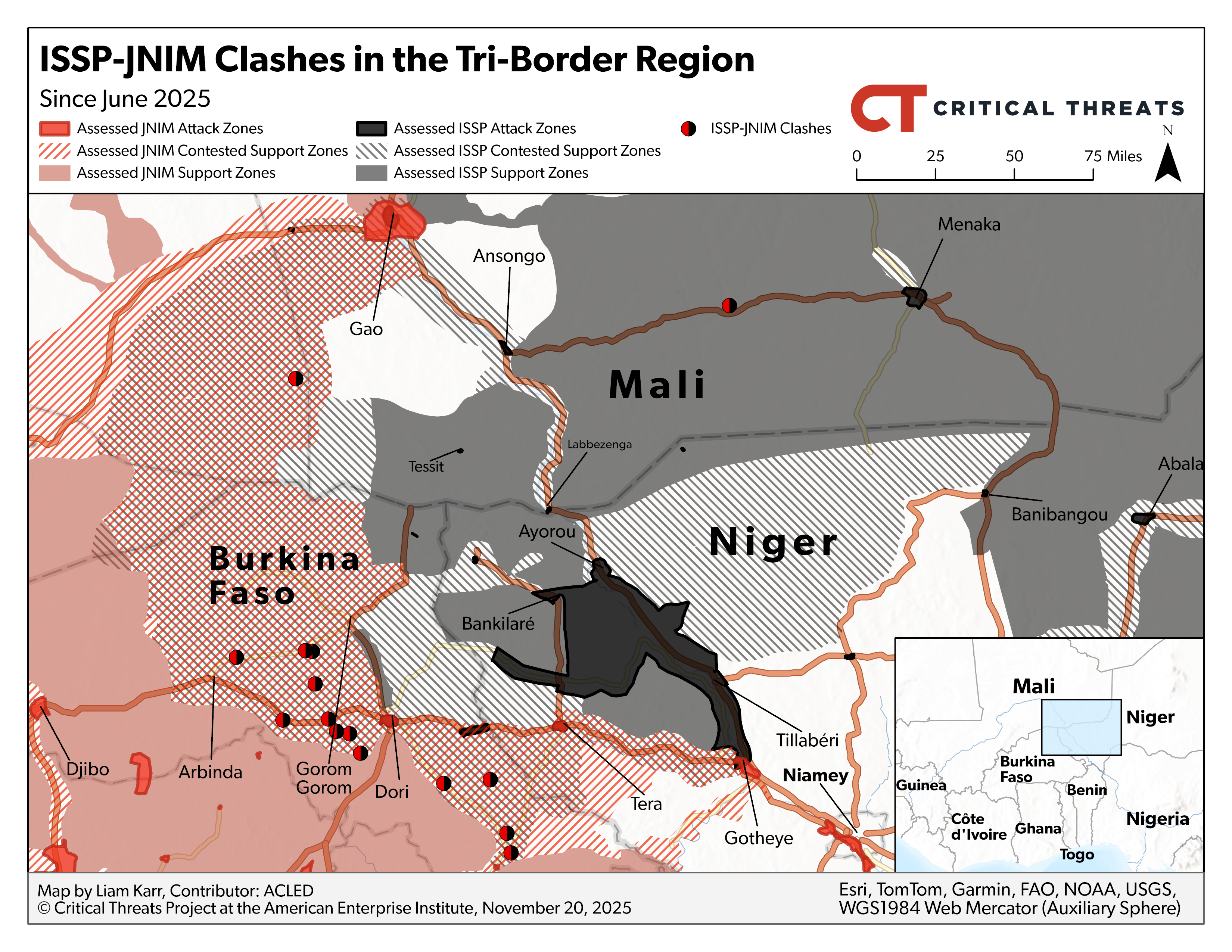

JNIM and ISSP infighting has reached its highest levels since 2023. ISSP killed 46 JNIM militants in clashes throughout northeastern Burkina Faso on November 9 in the deadliest inter-jihadi skirmish since July 2023. The attack was part of an escalation of inter-jihadi infighting in November that collectively killed at least 63 militants.[74]

Both sides reportedly sent hundreds of reinforcements to northeastern Burkina Faso in November. Roughly 500–700 ISSP reinforcements traveled from ISSP strongholds in neighboring Niger to support the offensive.[75] JNIM convened a council meeting on November 10 on how to counter ISSP’s offensive, deciding to send reinforcements from Gossi, Mali, to Arbinda, Burkina Faso.[76] Ousmane Dicko, deputy and younger brother to the leader of JNIM’s Burkina Faso-based Ansaroul Islam affiliate, was reportedly in attendance.[77] Ousmane Dicko released an audio on November 12, threatening to retaliate against ISSP.[78]

The recent spate of attacks is a part of a broader escalation in tensions since June 2025. JNIM and ISSP clashed eight times from June 22 to July 24 in what was the deadliest spate of inter-jihadi clashes since 2022 at that time.[79] ISSP and JNIM claimed to have killed 14 and seven militants, respectively.[80] The groups have collectively clashed more through November 2025 than they did in all of 2024. All but one of the skirmishes took place in Burkina Faso’s Sahel region.

Figure 10. ISSP-JNIM Clashes in the Tri-Border Region

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

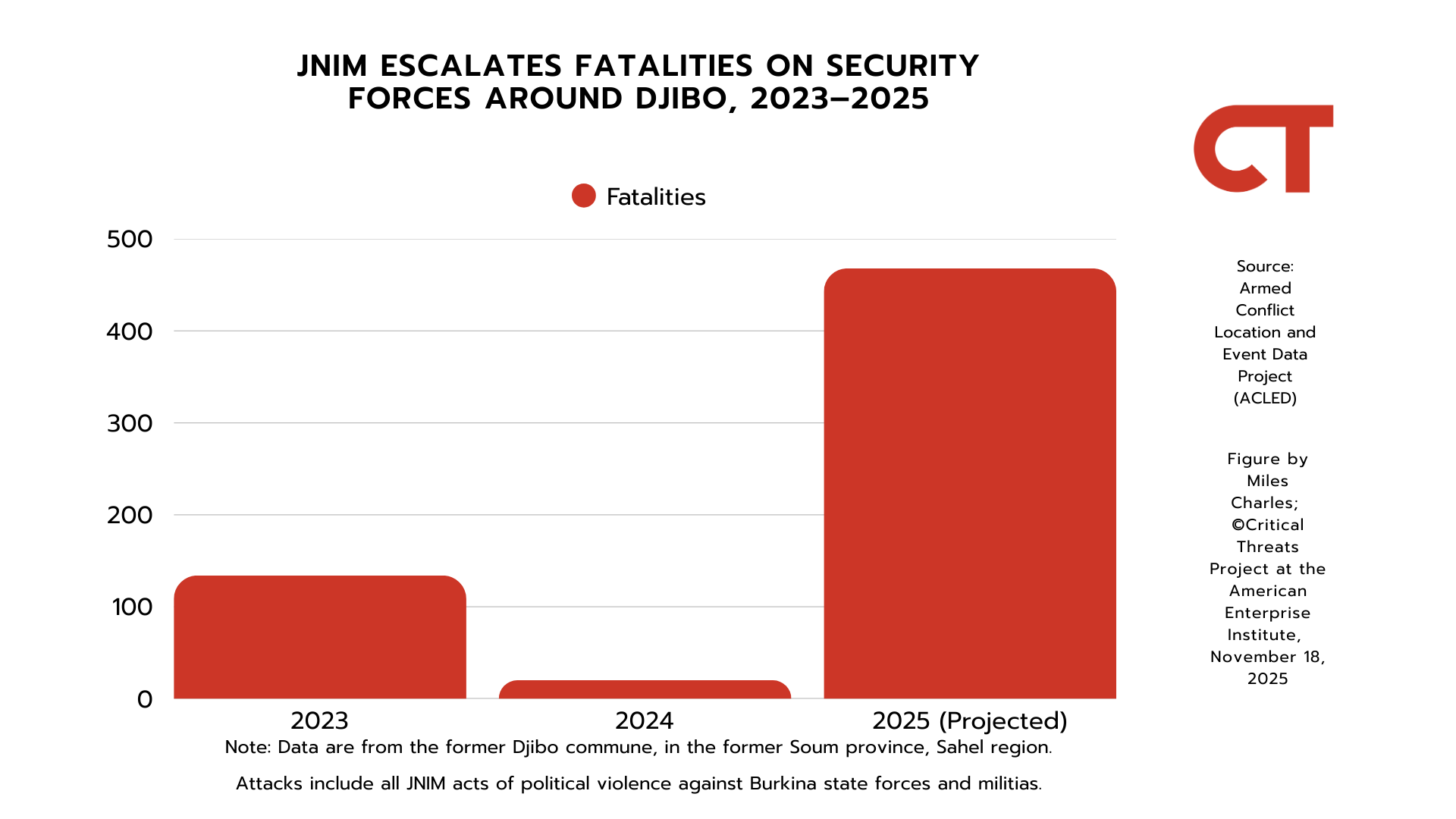

JNIM has escalated the scale of its attacks further west into Burkina Faso and could likely capture Djibo city should it choose to. The group has attacked security forces in the area more frequently in 2025 than in 2024 and has inflicted three times as many fatalities in Djibo commune in 2025 as it did in 2023 and 2024 combined.[81] JNIM has targeted Djibo commune in less than 10 percent of its attacks in 2025, yet those attacks have accounted for nearly half of the fatalities the group has inflicted across the former Soum province and Centre-Nord and Nord regions.[82] The group has conducted three mass fatality attacks on Djibo and its surrounding area in 2025. JNIM has conducted seven such attacks across the entire Sahel.[83] CTP defines a mass fatality attack as an event inflicting 50 or more fatalities.

Figure 11. JNIM Areas of Operation in the Tri-Border Region

JNIM may be targeting Djibo to consolidate cross-border support zones along the Burkina Faso–Mali border. Djibo is the provincial capital of Soum and sits near the Malian border. JNIM has historically maintained support zones in the tri-border area but has more brazenly moved freely through Soum in 2025. ACLED has recorded a record five reports of JNIM militant movements in 2025.[84] JNIM has also increasingly displaced villages across the border in central Mali since 2024.[85] The evictions and an increase in Malian air strikes suggest that the Malian junta is unable to regularly contest ground control of these areas, allowing JNIM to operate without significant enemy action.

Figure 12. JNIM Escalates Fatalities on Security Forces around Djibo, 2023–2025

Note: Data are from the Djibo commune, in the former Soum province, Sahel region. Attacks include all JNIM acts of political violence against Burkinabe state forces and militias.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

JNIM will likely use these support zones to facilitate subgroup cooperation between the Katiba Macina and Ansaoul Islam.[86] Djibo lies near the area of operational overlap between the two JNIM affiliates. CTP assessed in May that the two affiliates may have collaborated to orchestrate the Djibo attack that killed more than 200 people.[87]

Northern Mali

JNIM may have created a vacuum in northern Mali by repositioning forces from the north to reinforce its blockade, which ISSP could exploit to contest areas of northern Mali historically dominated by JNIM. The Malian army killed Ridwan al Ansari, a Tuareg JNIM field commander, during an ambush on a fuel convoy 58 miles west of Bamako on October 28.[90] Videos have since shown other Tuareg JNIM fighters participating in the blockade.[91] The presence of Tuareg fighters suggests that JNIM’s northern Mali–based, predominantly Tuareg subgroup Ansar al Din has redeployed fighters south to support the ongoing blockade on Bamako.[92] The presence of Tuareg fighters in southern Mali is unusual, as Mali’s Tuareg population is concentrated in northern Mali, and JNIM’s franchise model typically keeps fighters near their home regions.

JNIM has decreased its attacks on security forces in northern Mali since the start of its blockade on September 3. ACLED has recorded seven JNIM attacks in northern Mali in the two months since the blockade began at the beginning of September, compared to 26 attacks in the preceding two-month period.[93] Prior to that, JNIM had averaged roughly eight attacks per month in northern Mali in 2025.[94]

ISSP may be exploiting the vacuum to begin contesting JNIM-controlled territory around Kidal. ISSP killed six civilians and kidnapped seventeen others near the Kidal-Gao regional border on October 26.[95] The attack marks ISSP’s first recorded attack in the Kidal region, nearly hundreds of miles north of its main area of operations along the Mali-Niger border.[96] JNIM and Tuareg separatists, with long-standing ties to JNIM, have dominated Kidal and its surrounding area since their emergence in 2012.

Figure 13. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in Northern Mali

Malian Forces and their Russian allies have increased joint engagements in northern Mali. ACLED has recorded nearly double the number of Malian and Russian security-related events in northern Mali since the start of 2025 compared to the entirety of 2023 and 2024 combined.[97] Cooperation notably increased following the Wagner Corps' departure on June 6, with 91 percent of joint Malian-Russian engagements correlated events occurring after the Russian presence in Mali formally transitioned to Africa Corps.[98]

Figure 14. Malian Forces and Russian Mercenaries Increase Joint Engagements in Northern Mali

Note: Data are from Gao, Kidal, Ménaka, and Timbuktu regions, Mali. Engagements include any event with both Malian and Russian forces listed as actors.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data

Northern Sahel

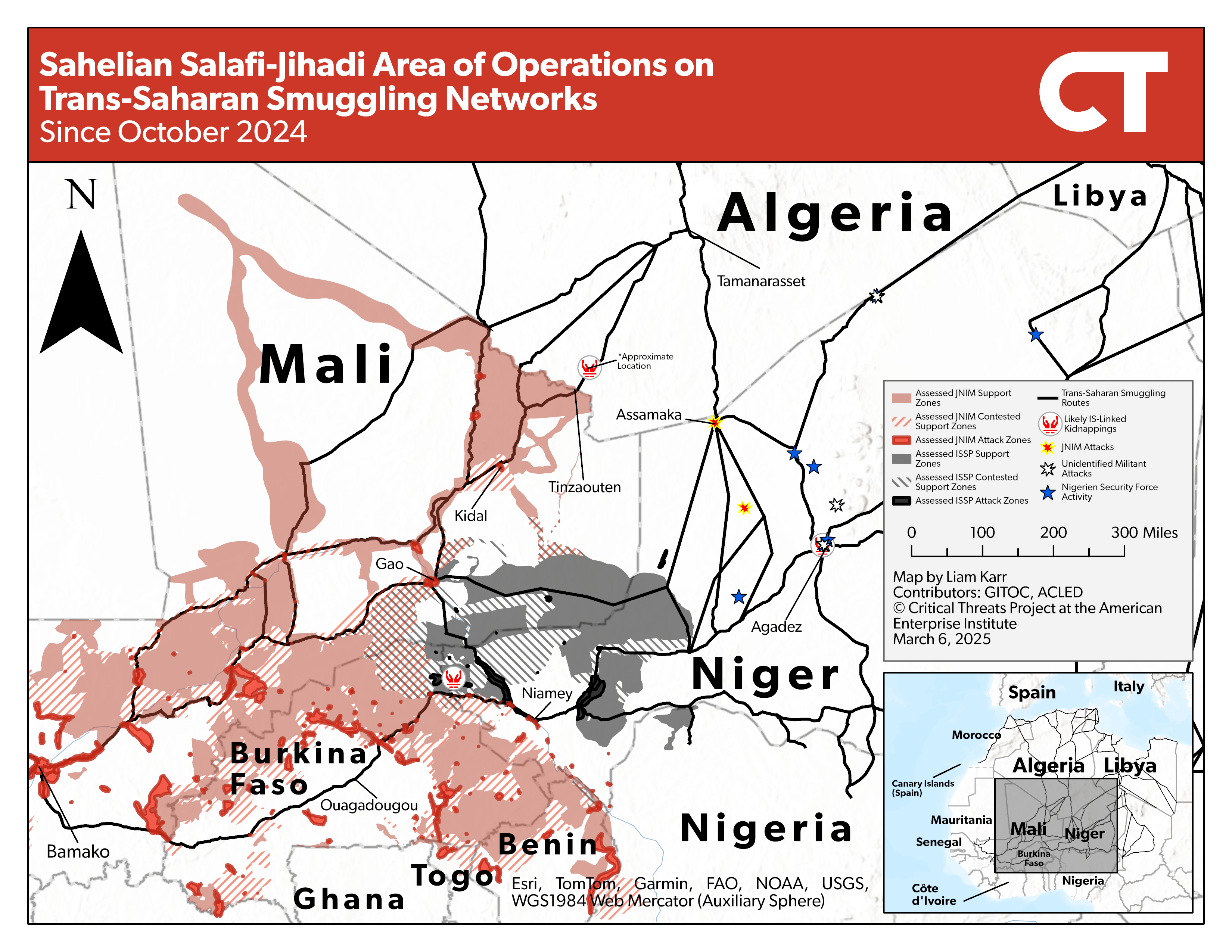

JNIM and ISSP have operationalized their presence along key trans-Saharan smuggling nodes in northern Niger. Both groups collaborate with local criminal groups to reinforce their activity along key trans-Saharan smuggling routes. ISSP coordinated two kidnappings with local bandits in northern Niger in 2025, while JNIM has reportedly worked with local bandits to support attacks on Nigerian forces along key smuggling nodes.[99] JNIM killed at least 11 soldiers in an attack on a security post in Northern Niger on February 28, reportedly to prevent disruptions in trafficking networks.[100] The departure of US and French forces—particularly the US drone base in Agadez—has undermined intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support in these remote areas, creating a vacuum that both groups have exploited.[101]

Figure 15. Sahelian Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation on Trans-Saharan Smuggling Networks

Source: Liam Karr; Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

Greater influence over trans-Saharan networks may expand both groups’ external reach, increasing the threat of external plots in North Africa and Europe. A strengthened presence along trans-Saharan smuggling networks will strengthen connections between the Salafi-jihadi affiliates in the Sahel and facilitation networks in North Africa. The United Nations reported in 2024 that JNIM remains active in North Africa, using it as a transit and logistic corridor to support its activity in West Africa.[102] ISSP has shown a clear intent to use its trans-Saharan networks to support attacks in North Africa and Europe. Moroccan police foiled two IS attack cells with ties to ISSP in January and February 2025.[103] Moroccan forces also disrupted three IS cells facilitating foreign fighters’ travel to ISSP in Mali between October 2023 and February 2024.[104]

Eastern Burkina Faso

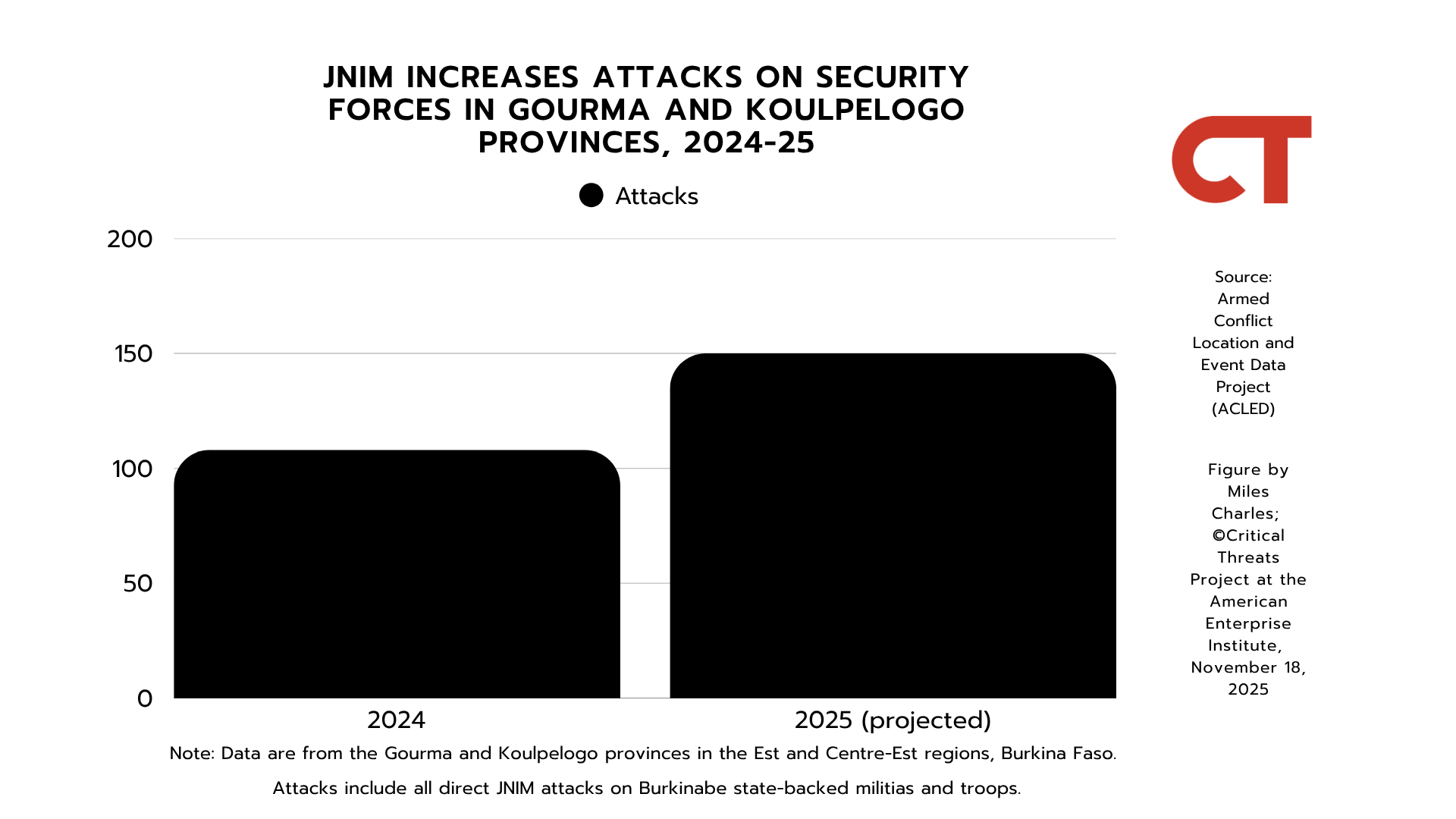

JNIM has escalated the rate of its attacks in eastern Burkina Faso throughout 2025. The group has averaged six more attacks a month on security forces in eastern Burkina Faso in 2025 than in 2024 and has set an all-time high in attacks across the Est and Centre-Est regions.[105] JNIM has notably increased its activity in Gourma and Koulpelogo provinces and is on pace to carry out nearly twice as many attacks in 2025 as in 2024.[106] Burkinabe forces have not matched JNIM’s escalated tempo and are projected to record a 27 percent decrease in counterinsurgency operations in 2025 from 2024.[107]

Figure 16. JNIM Increases Attacks on Security Forces in Gourma and Koulpelogo Provinces

Note: Data are from former Gourma and Koulpélogo provinces in the former Centre-Est and Est regions, Burkina Faso.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

The attacks have targeted key road arteries in the region, degrading state control over military ground lines of communication and economic trade arteries. All of JNIM’s attacks in the Gourma and Koulpelgo provinces have occurred within 12 miles of the N4, N16, N17, and N18 highways.[108] The group is on pace to double the number of attacks against forward operating bases and patrol forces along these roads in 2025 compared to 2024.[109] These attacks restrict the freedom of movement of security forces along these key roads and increase the cost of contesting JNIM, enabling the group to strengthen and expand its support zones.

Figure 17. JNIM Areas of Operation in Eastern Burkina Faso

The attacks risk degrading already volatile trade arteries connecting the landlocked Sahel countries to ports in Togo and Benin. The four roads anchor the Cotonou–Fada N’Gourma–Niamey and Lomé–Ouagadougou–Niamey corridors, responsible for 40 percent and nearly 20 percent of Burkina Faso’s and Niger’s import volume, respectively.[110] The highways are also part of the Trans-Sahelian Highway, connecting the capitals of Senegal, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Niger.[111]

JNIM also exploits smuggling networks along these roadways. The group has taxed independent smugglers along these roads since 2021 while simultaneously using them to smuggle stolen gold and livestock to Burkina Faso, Benin, and Togo.[112] JNIM reportedly makes $42,500 to $50,000 a month from cattle rustling in northeastern Burkina Faso, although there are no concrete figures for areas near the Benin and Togo border.[113]

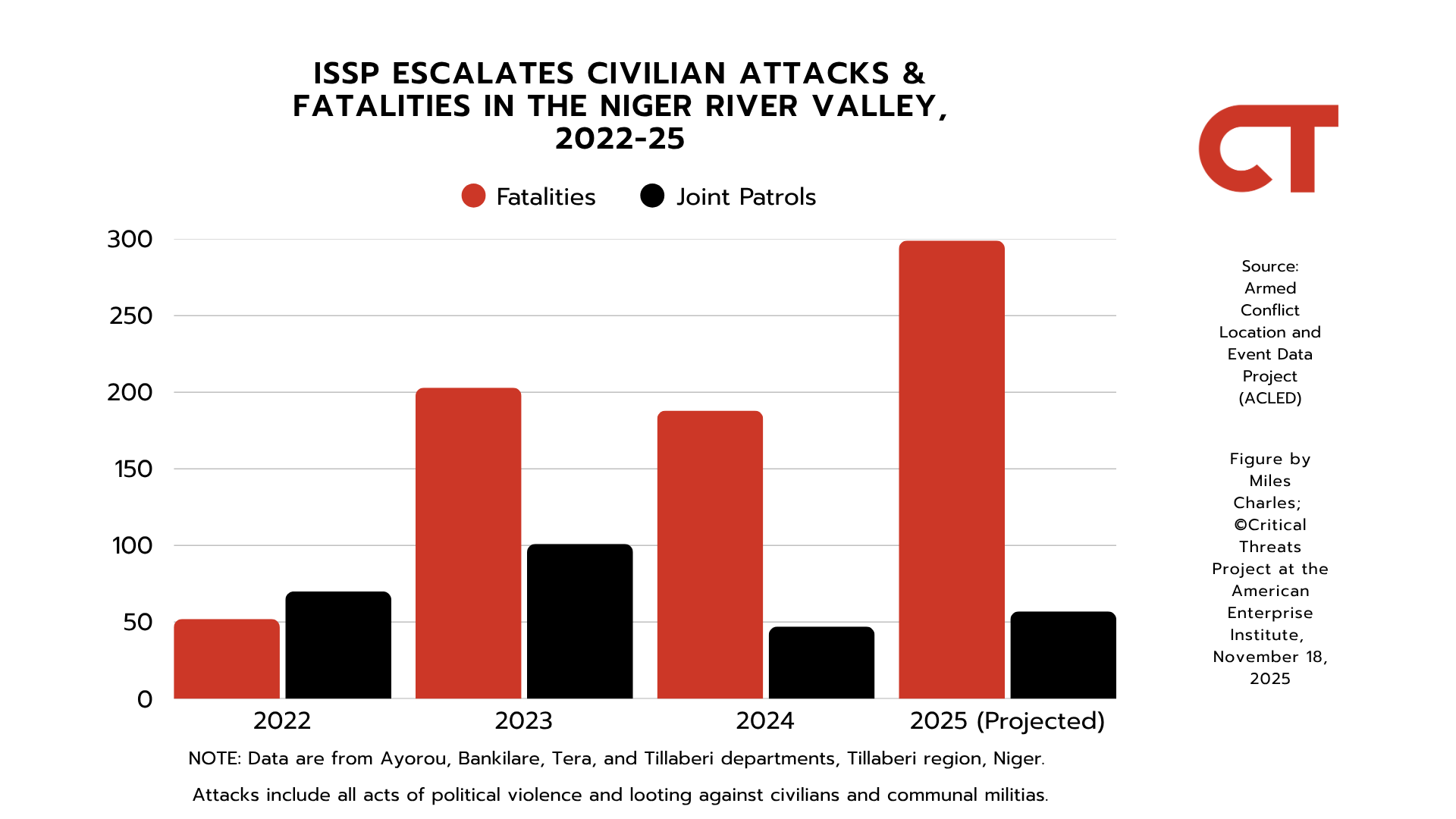

Niger River Valley

ISSP has escalated the severity of attacks against civilians and civilian militias in the Niger River Valley to quash civilian resistance and establish support zones. The group has historically targeted civilians in the Niger River Valley to play on ethnic tensions between the nomadic Fulani and other rival ethnic groups.[114] ISSP has increased the severity of these attacks every year since 2022. ISSP’s attacks on civilians and civilian militias in the Niger River Valley are nearing its 2022 and 2023 baseline, but it is on pace to inflict nearly as many fatalities in 2025 as it did from 2022 to 2024 combined.[115]

Figure 18. ISSP Escalates Civilian Attacks and Fatalities in the Niger River Valley

Note: Data are from Ayorou, Bankilaré, Téra, and Tillabéri departments, Tillabéri region, Niger. Attacks include all acts of political violence and looting against civilians and communal militias.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data

ISSP is particularly targeting areas around the N1 and N23 highways, likely to degrade lines of communication and isolate the region from the capital. ISSP has attacked civilians within 15 miles of the N1 or N23 in 70 percent of its attacks in 2025.[116] The two highways are the road arteries of the Niger River Valley, connecting Ayerou, Tera, and Tillaberi—the three department heads and largest towns in the area—to Niamey. ISSP will be able to further pressure the capital and target hardened security positions along major roadways with greater support zones in the valley.

Figure 19. ISSP Areas of Operation in the Niger River Valley

ISSP is likely using its support zones along the Mali-Niger border to support efforts in the Niger River Valley. ISSP’s rate of engagement along the Mali-Niger border has decreased throughout 2025, but the attacks it has conducted have become deadlier.[117] ACLED has also recorded an increased number of ISSP support activities in the Tillaberi region and continued reports of ISSP control in the Tahoua region, which CTP has assessed collectively form a major ISSP hub.[118] These trends indicate that ISSP is now able to move more freely and stage large-scale attacks along and across the border. The group used these zones to massacre at least 70 civilians in a commune in the Tillaberi department in 2025.[119]

The junta has begun to expand state-sponsored militias in response to ISSP’s escalation. Junta-supported civil society organizations announced in August 2025 plans for a state-supported civilian militia called the Garkouwar Kassa (Shields of the Fatherland).[120] Civilian volunteers will train in Niamey and deploy to conflict zones alongside Nigerien security forces.[121]

The communal mobilization may lead to an increase in communal violence that ISSP has historically capitalized on to recruit. ISSP exploited state-led communal mobilization programs to gain footholds in various parts of the Tillaberi region in the late 2010s.[122] This trend forced the Nigerien government to reduce support for militias and sponsor communal reconciliation programs, which led to a decrease in ISSP activity in northern Tillaberi.[123]

The Garkowar Kassa resemble the Volontaires pour la defense de la patrie (VDP), state-backed civilian militias in Burkina Faso, which have increased counterproductive communal mobilization and violence against civilians. Burkina Faso began formalizing preexisting militias under the VDP in 2020.[124] The junta’s use of the VDP alongside state forces has led to new records for civilian fatalities inflicted every year since 2023.[125] The VDP has disproportionately and indiscriminately targeted Fulani due to their suspected ties to insurgency groups and relative lack of Fulani representation in the militias, reinforcing a self-fulfilling prophecy.[126]

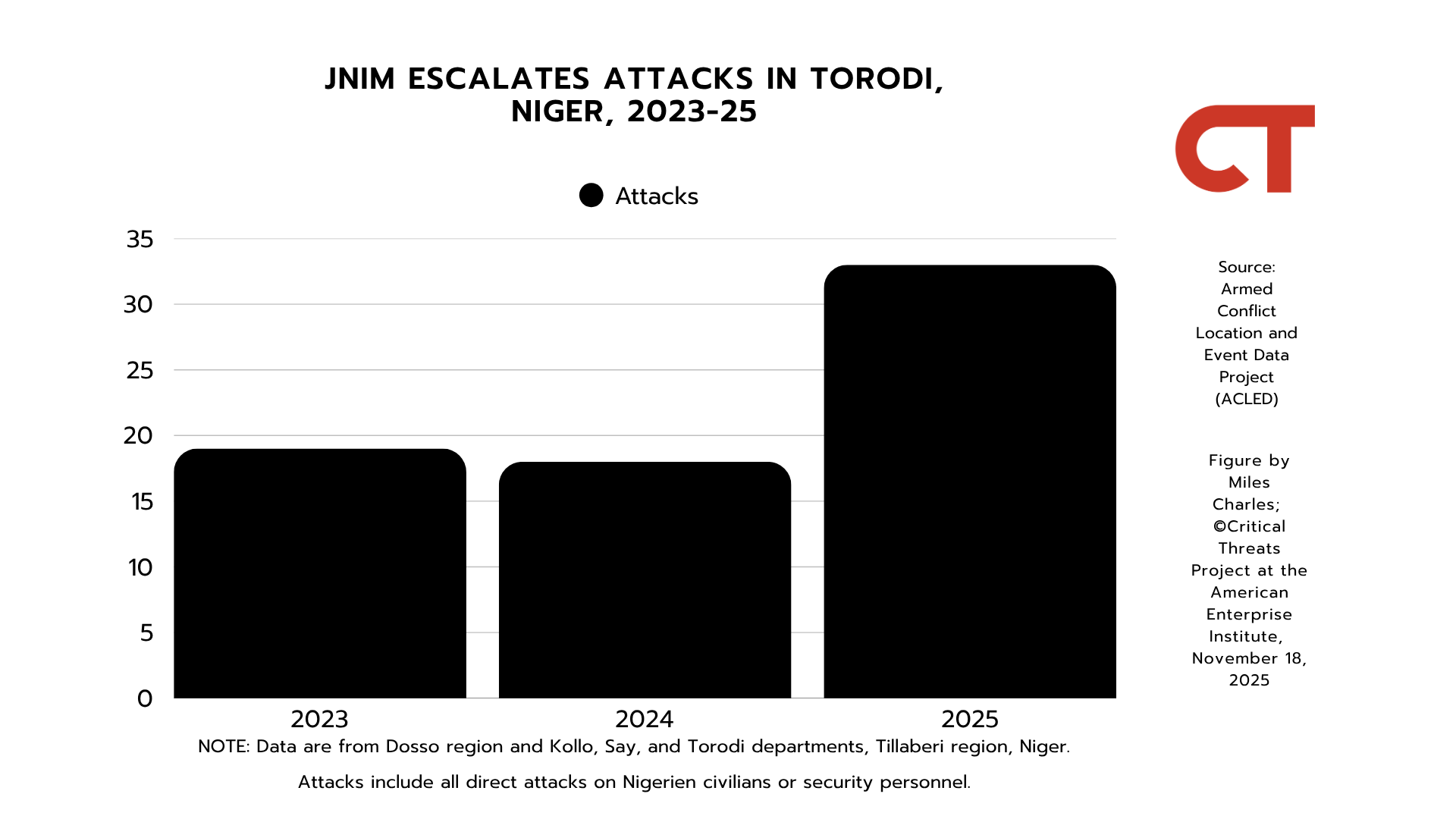

Southwestern Niger

JNIM is attempting to expand support zones in Torodi province, southwestern Niger, which is helping to isolate Niamey. The group is on pace to attack civilians and security personnel in Torodi more in 2025 than in 2024 and 2023 combined.[127] JNIM has particularly targeted security forces, attacking them in 70 percent of its attacks.

Figure 20. JNIM Escalates Attacks in Torodi, Niger

Note: Data are from Dosso region and Kollo, Say, and Torodi departments, Tillabéri region, Niger.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data

JNIM has specifically targeted the N6, the province’s primary road leading to Niamey. The group evicted five villages in Torodi on March 25 to blockade Makalondi, a key town on the N6 about 50 miles southwest of Niamey.[128] JNIM has since restricted the movement of civilian and security forces along the N6 as part of this blockade. The group has attacked civilians along the N6 twice since March 2025 and targeted security personnel with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) 10 times.[129] Security personnel have diffused an additional 11 IEDs in the vicinity of the N6 throughout 2025.[130]

JNIM will draw closer to its regional rival, ISSP, as it expands support zones, risking an escalation in inter-jihadi fighting. Southwestern Niger has become an increasingly important area to both actors, linking ISSP to its subgroup along the Niger-Nigeria border, Lakurawa, while bridging JNIM territory in Burkina Faso and along the Benin-Nigeria border. As both actors expand their territory the risk of zones colliding increases, which could open a new theater of Salafi-jihadi infighting. The two groups have experienced a rise in inter-jihadi skirmishes in northeastern Burkina Faso, an area both groups contest for control.

Southwestern Niger has underlying ethnic tensions between the pastoralist Fulani and the sedentary Hausa and Songhai-Zarma that both actors could exploit. The Fulani compete with their sedentary rivals for grazing land and water while also facing ethnic-based state targeting. Southwestern Niger houses the majority of Niger’s Fulani population, which is concentrated in JNIM’s territory in Tillaberi and along the ISSP-dominated Niger-Nigeria border.[131]

Figure 21. Sahelian Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in Nigeria

Northwestern Nigeria

ISSP has operationalized rear support zones in Nigeria to support activity in southwestern Niger. Lakurawa, an ISSP subgroup, operationalized support zones stretching from the border between Dosso, Tahoua, and Tillaberi in Niger down to Sokoto and Kebbi in Nigeria in 2025. The group has been in the area as a rear support zone linking ISSP and ISWAP since 2018, but likely operationalized in response to increased counterinsurgency pressure in late 2024.[132] The group is now on pace to conduct more attacks in Niger in 2025 than 2022 to 2024 combined.[133] The attacks have allowed ISSP to better disrupt lines of communication on the Nigerien side of the border and assert a degree of control, including taxation, on towns in the Loga and Dogondoutchi departments in 2025.[134]

A consolidated foothold will enable Lakurawa to better pressure Niamey and strengthen ties east with ISSP’s main area of operations and west with ISWAP. The UN has reported since 2024 that ISWAP has established cells in northwestern Nigeria to link ISWAP to Lakurawa support zones in Sokoto, Nigeria.[135] The ISWAP-based West Africa regional IS office—al Furqan—coordinates the cells to facilitate the movement of ISWAP weapons, fuels, equipment, and fighters to support ISSP activity in Burkina Faso and Mali.[136]

JNIM has operationalized rear support networks in Nigeria to support opening a second front in Benin. JNIM attacked a Beninese outpost in Basso, three miles from the Nigerien border in the Borgou department, on June 12.[137] The attack’s proximity to the border and distance from JNIM’s primary area of operations near the Park W complex indicate that the attackers likely came from Nigeria. JNIM militants in Nigeria’s Kainji reserve, which began settling in the area in 2021, likely carried out the attack.[138] JNIM militants released a video along the border with Benin on July 12 stating their intent to increase attacks on Benin, Togo, and Ghana.[139]

JNIM will likely use these zones to escalate its attacks in Nigeria. JNIM claimed to have attacked Nigerian troops in the Kwara state, adjacent to the Kainji reserve, on October 28.[140] This marks the group’s first-ever attack in Nigeria. CTP assessed in June 2025 that JNIM’s presence in the Kainji reserve is an attack risk for Nigeria, especially given the likely fluid relationship among JNIM-linked militants and other, more Nigerian-focused groups in the Kainji area.[141]

JNIM will likely lash out if Nigerian forces increase counterinsurgency pressure, as Salafi-jihadi groups have historically done. JNIM similarly operationalized support cells in Benin and Togo in 2022 when it came under increased counterinsurgency pressure, and ISSP’s Lakurawa did the same in 2025.[142]

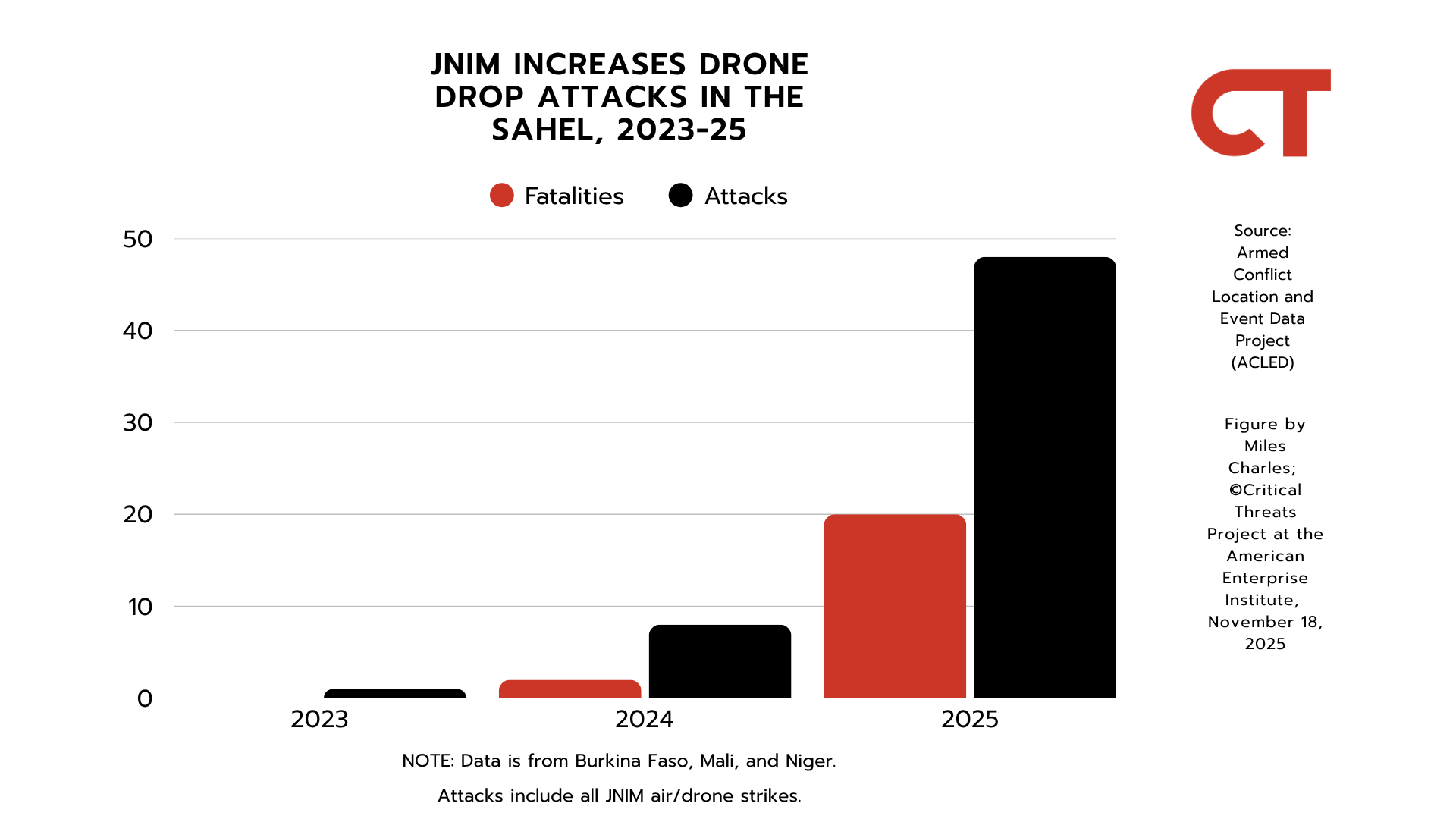

Drone Drops

JNIM has exponentially increased drone drop attacks since first introducing them in 2023. CTP defines “drone drops” as the use of a commercial drone to drop grenades, improvised explosive devices, mortars, or other explosives onto an enemy position. JNIM has conducted five times as many drone drop attacks through November 2025 as it did in 2023 and 2024 combined.[143] Drone drops have supplemented mortar and rocket fire, enabling JNIM to conduct indirect strikes on hardened targets more frequently. The group has averaged six indirect strikes a month in 2025, up from three in 2024.[144] JNIM is the only nonstate actor in the world to sustain this level of drone attacks across multiple countries.[145]

Figure 22. JNIM Increases Drone Drop Attacks in the Sahel

Note: Data are from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

Source: Miles Charles; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data

The growing accessibility of drones has facilitated their integration into the group’s modus operandi. The cost of drones has fallen as low as $450, giving JNIM a cheaper, more precise method of attack than mortars, which must be stolen or bought for $650.[146] The Azawad Liberation Front (FLA), a separatist Tuareg group in northern Mali with informal ties to JNIM, used a fiber optic suicide drone for the first time in the Sahel in 2025.[147]

Large-Scale Attacks

JNIM and ISSP have conducted large-scale attacks more frequently in 2025, signaling an increase in their operational capacity. JNIM and ISSP are on pace to collectively conduct a record number of large-scale attacks—defined as an event inflicting 20 or more fatalities—in 2025. The two actors have averaged five such attacks a month in 2025, up from four in 2024.[148] The severity of these attacks has also increased, with an average of seven more fatalities per attack in 2025 than in 2024.[149] The two groups have notably increased the rate of mass fatality attacks, defined as events inflicting 50 or more fatalities. They have conducted as many such attacks through November 2025 as they did in the entirety of 2024.[150]

Lake Chad

Background: The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in the Lake Chad Basin

The Salafi-jihadi movement in the Lake Chad Basin originated from a religious movement led by Mohamed Yusuf in northeastern Nigeria in the 1990s.[151] Yusuf founded JAS, commonly known as Boko Haram, in 2002. The group turned to open violence in 2009 after police harassed members and the Nigerian military extrajudicially killed Yusuf.[152]

Abubakr Shekau succeeded Yusuf as Boko Haram’s leader in 2010. The group engaged in extreme violence under Shekau’s leadership, massacring thousands of innocent civilians in northeastern Nigeria.[153] Boko Haram rose to international prominence through notorious attacks like the 2014 kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls.[154] The group also operated in the Nigerian capital and south-central Nigeria in the mid-2010s and regularly attacked neighboring countries in the Lake Chad Basin: Cameroon, Chad, and Niger.[155]

Shekau’s radical takfiri ideology, which permitted excessive violence against any Muslim not actively supporting the group, led to the formation of several splinter groups. Some disillusioned members left the group in 2012 and created Jama’atu Ansar al Muslimin fi Bilad al Sudan, widely known as Ansaru, with support from AQIM.[156]

The Islamic State entered the Lake Chad theater when Shekau pledged allegiance to the group’s leader in 2015 and rebranded Boko Haram as ISWAP.[157] Shekau’s leadership continued to cause division, however, and a group of commanders with closer ties to Islamic State leadership ousted him in 2016.[158] Shekau and his remaining followers returned to the group’s original name but continued to claim membership in the Islamic State.

ISWAP and Boko Haram regularly clashed in northeastern Nigeria in the years following the 2016 split, with ISWAP ultimately gaining the upper hand.[159] Shekau killed himself to evade capture by ISWAP fighters in May 2021.[160] Hundreds of Shekau’s followers subsequently defected to ISWAP or surrendered to the Nigerian government.[161] ISWAP is now the dominant group in northeastern Nigeria, although some Boko Haram factions are still active.[162]

The Nigerian counterterrorism strategy has reinforced ISWAP and Boko Haram’s long-standing strength in rural northeastern Nigeria over the last several years. Nigerian security forces shifted strategies to concentrate ground forces in population centers and increase air strikes in rural areas in 2019.[163] This change ceded swaths of rural northeastern Nigeria to Salafi-jihadi groups but decreased attacks on major population centers as militants gathered in smaller numbers to avoid air strikes. Counterterrorism forces launched an offensive into Salafi-jihadi havens in northeastern Nigeria in spring 2022 that has posed the largest challenge to militant control over rural areas since 2015.[164]

Deteriorating security conditions across Nigeria have helped Salafi-jihadi militants expand their areas of operation since 2020.[165] ISWAP took advantage of its improved position and widespread instability in Nigeria to build attack cells across the country in 2022, including in the Nigerian Federal Capital Territory.[166] Boko Haram had been active in some of these areas in the 2010s, raising the possibility of ISWAP using pre-established jihadist networks.[167] Other factions, including Ansaru, Boko Haram, and the Sahelian-based groups have also established themselves in northwestern Nigeria since 2020.[168] This expansion raises the possibility of cross-group collaboration and signals a potent Salafi-jihadi threat outside northeastern Nigeria for the first time since 2017.[169]

Campaign and Map Updates

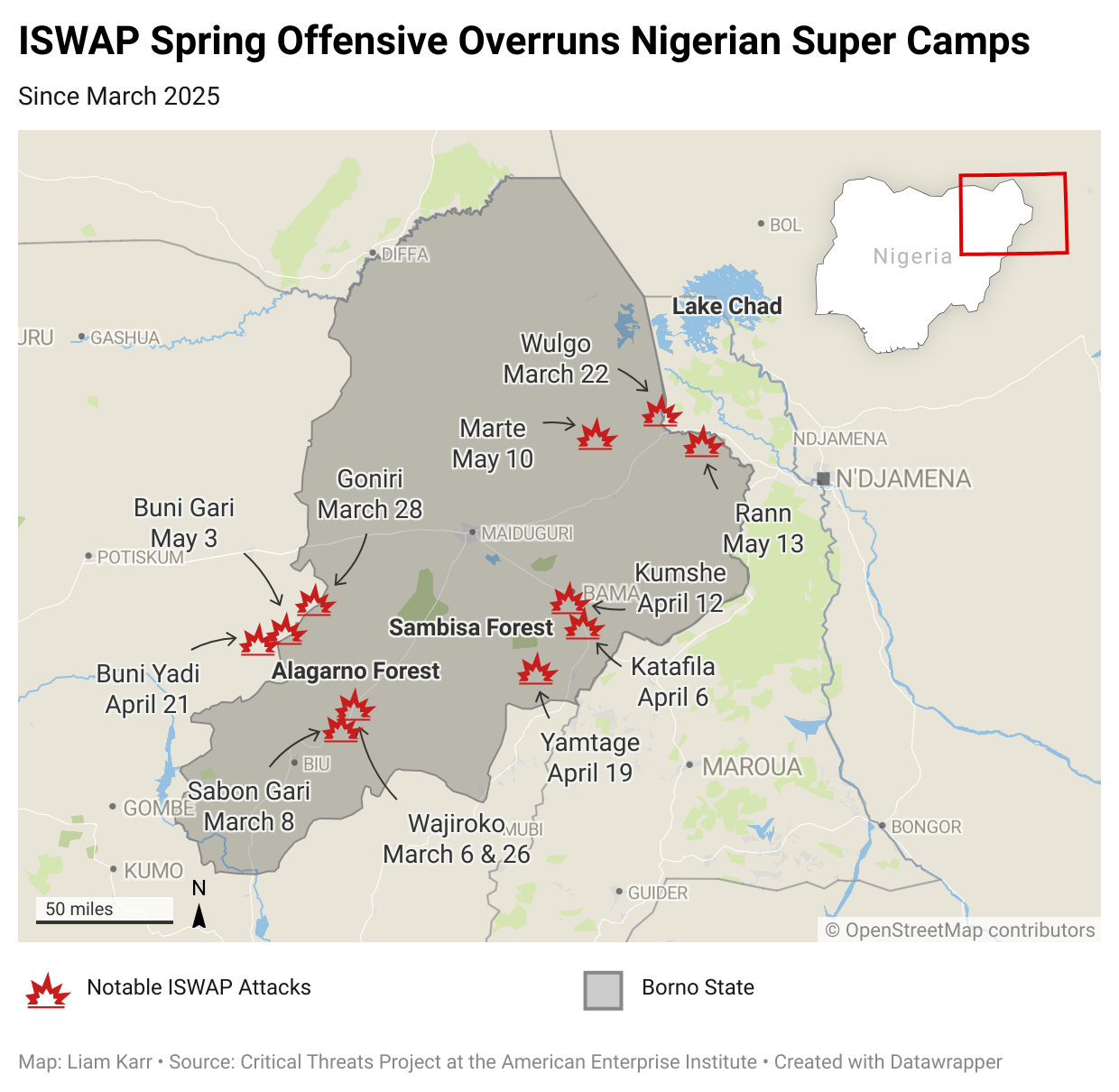

ISWAP

ISWAP has nearly overrun two dozen Nigerian security positions in northeastern Nigeria since March 2025 as a part of its “burn the camps” offensive. ISWAP has overrun Nigerian security positions 23 separate times since March 2025 as part of its offensive.[170] The campaign has spread across ISWAP’s area of operations in northeastern Nigeria, but the group has concentrated attacks near its havens in the Alagarno forest in March, the Sambisa Forest, and the Mandara Mountains in April, and closer to the Lake Chad Basin in May.

Figure 23. ISWAP Spring Offensive Overruns Nigerian Super Camps

Source: Liam Karr.

The offensive shows that ISWAP has adapted to the Nigerian government’s “super camp” and containment strategy. The Nigerian army consolidated its forces in “super camps” based in key population centers beginning in 2019. The strategy intended to concentrate soldiers in heavily fortified positions from which they can respond to insurgent activity but ceded large swaths of rural areas to insurgents as a consequence.[171] ISWAP has had newfound success attacking these super camps in 2025 by launching nighttime raids.[172] Militants have targeted bridges and roads between the camps–and launched diversionary attacks on nearby positions–to prevent reinforcements from reaching targeted bases.[173] ISWAP has also targeted resettled villages near these super camps, further undermining the population-centric component of the super camp strategy.[174]

ISWAP is strengthening as regional counterterrorism in the Lake Chad Basin is decreasing. ISWAP militants have seized weapons, ammunition, and other equipment before burning the bases. These raids have drastically improved ISWAP’s armory.[175] ISWAP in late 2024 began using drones to drop explosives–a tactic that has become common practice in West Africa.[176] ISWAP explicitly declared that it had defeated the super camp strategy after a major attack in January 2025, prior to the latest offensive, and threatened to shift its focus to capturing major population centers in the near future.[177] ISWAP’s growing weapons would help enable such attacks.

The degradation of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) has undermined regional security cooperation. The MNJTF consisted of the four countries bordering Lake Chad—Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria—and Benin. Niger withdrew from the MNJTF in March 2025, however.[178] The MNJTF has been unable to defeat the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in the Lake Chad Basin due to weak structural commands, short-lived operations, and an underfunded civilian oversight committee that cannot exert authority.[179] The force has conducted regular “mowing the grass” offensives, however, which help contain the insurgency, decrease the total number of insurgent attacks, and resettle refugees and businesses.[180]

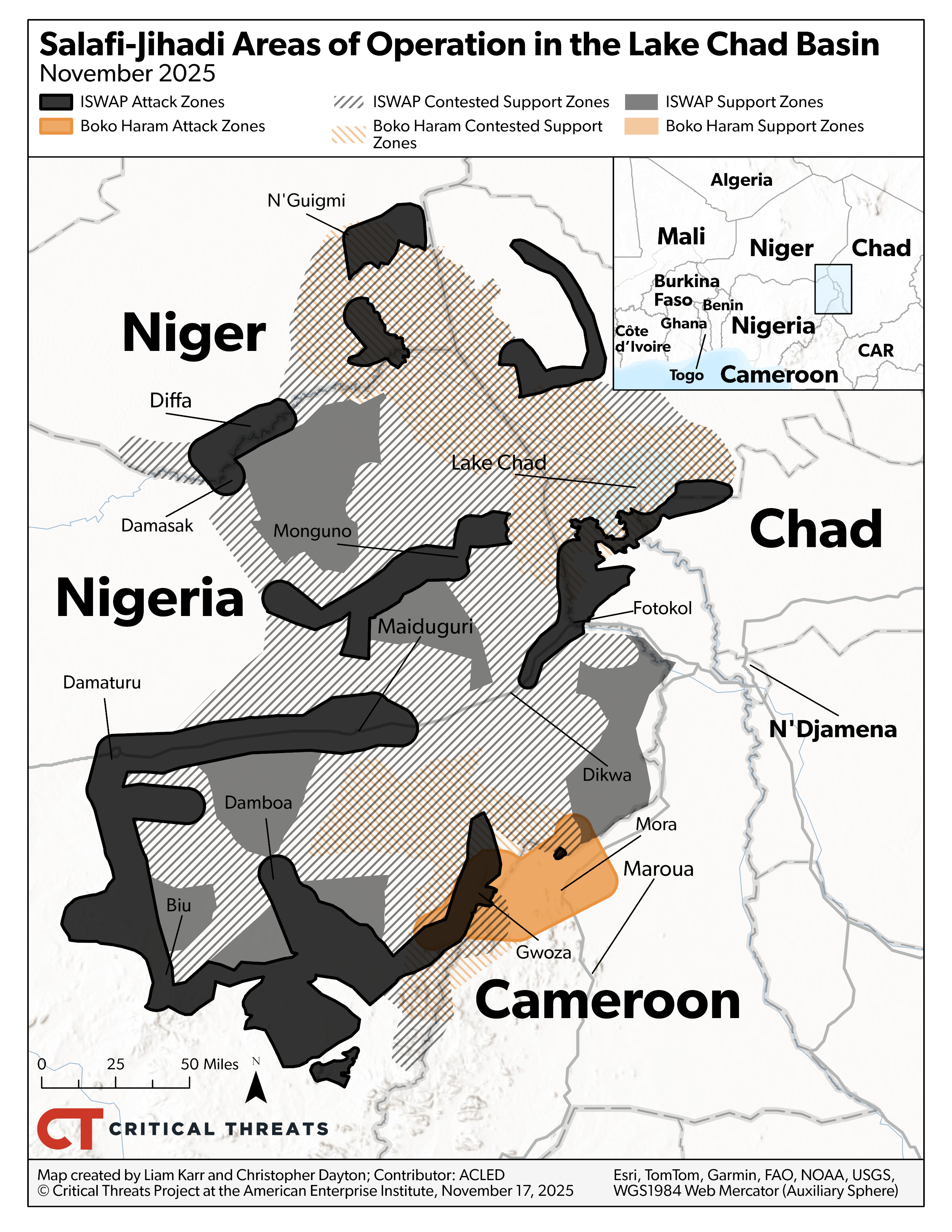

Figure 24. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Lake Chad Basin

Source: Liam Karr and Christopher Dayton.

Boko Haram

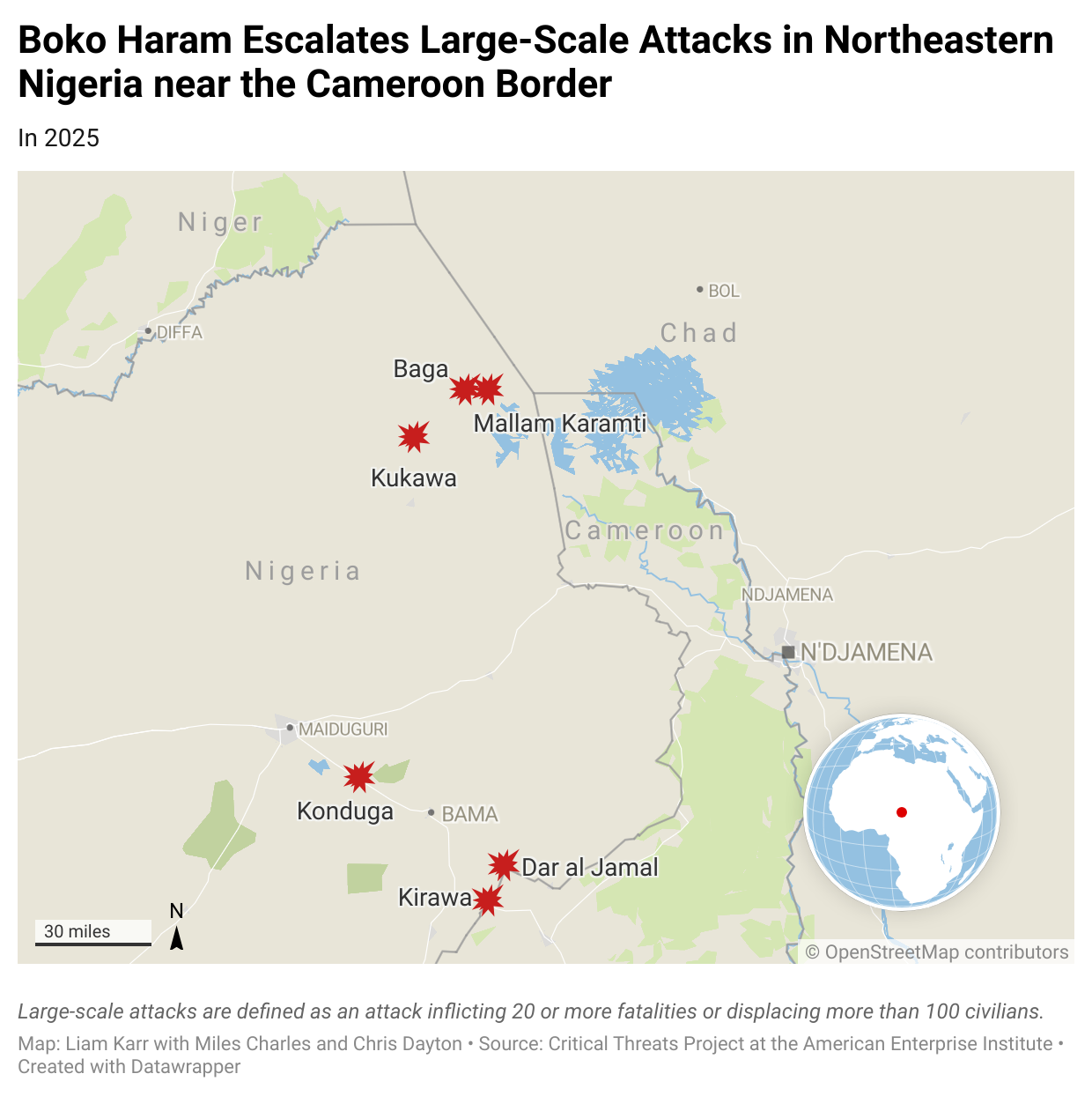

Boko Haram has escalated the scale of its attacks along the Cameroon-Nigeria border throughout 2025. The group has conducted six large-scale attacks along the Cameroon-Nigeria border in 2025, which CTP defines as an attack inflicting 20 or more fatalities or displacing more than 100 civilians–compared to one in 2024.[181] Several of these attacks were retaliatory, likely to coerce local populations into working with the group. Boko Haram massacred 100 civilians, whom it accused of spying for ISWAP in northern Nigeria, along the border, in early 2025.[182] The group killed another 60 civilians, whom it accused of collaborating with the Nigerian military in Dar Jamal, another border town, in September 2025.[183]

Figure 25. Boko Haram Escalates Large-Scale Attacks in Northeastern Nigeria near the Cameroon Border

Source: Liam Karr.

Boko Haram is exploiting the deterioration of military infrastructure along the border. Nigerian and Cameroonian troops have abandoned border posts due to increased attacks, enabling Boko Haram to move more freely along the border.[184] Cameroon and MNJTF soldiers abandoned the town of Kirawa following a Boko Haram attack on August 7.[185] Boko Haram then attacked the town on September 30, displacing 5,000 residents.[186] ISWAP’s “Burn the Camps” offensive has attacked 34 camps in 2025, forcing three to permanently vacate and others temporarily close, further degrading border security.[187] Niger’s withdrawal from the MNJTF in March 2025 further degraded border security cooperation, allowing Boko Haram to strengthen its logistic corridors.[188]

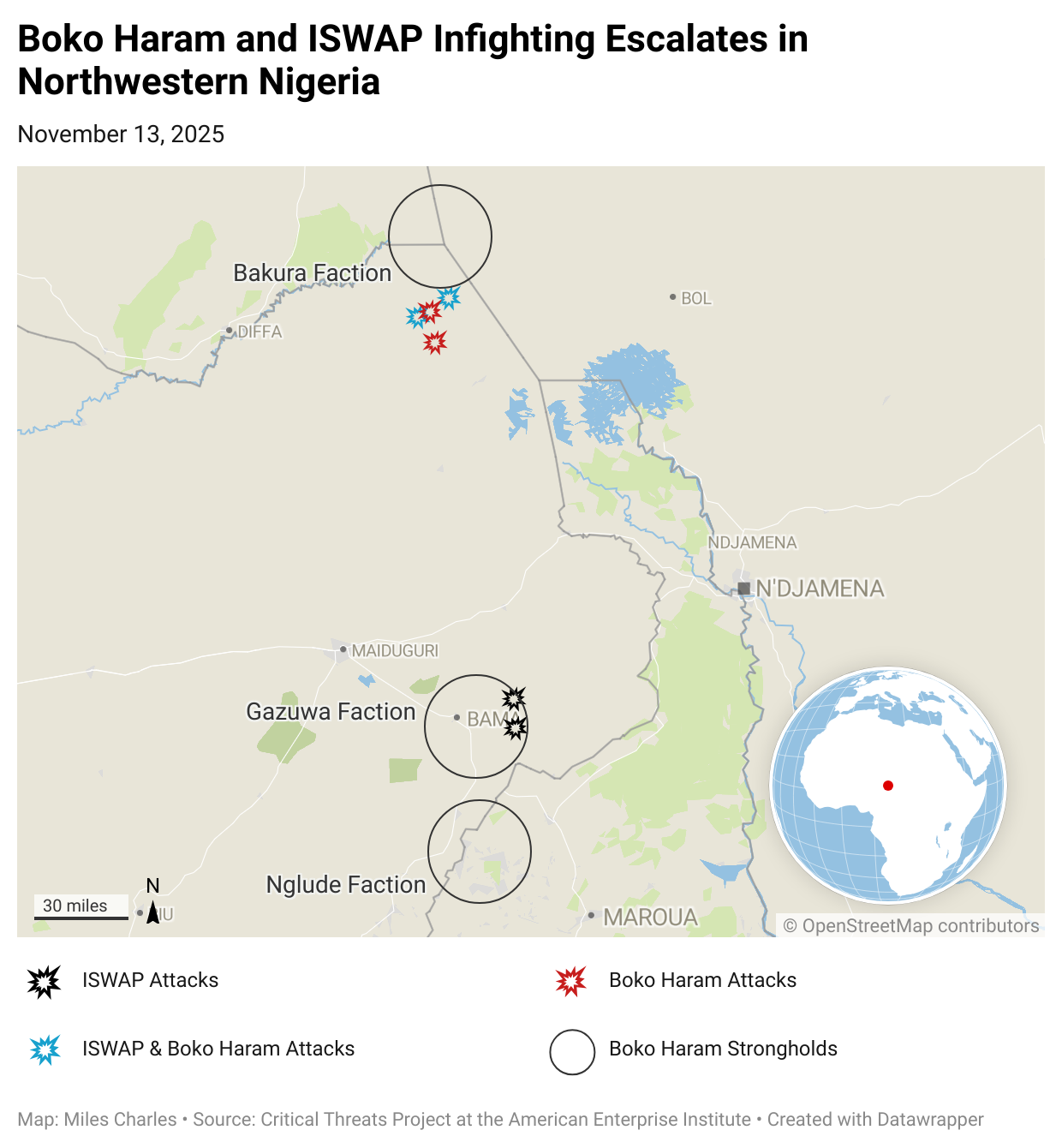

Infighting

Boko Haram and ISWAP have engaged in an escalatory cycle of retaliation since October 2025, resulting in the deadliest period of inter-jihadi fighting in years. The uptick in fighting began after Boko Haram attacked civilians in two villages within ISWAP’s sphere of influence near the Sambisa Forest and Mandara Mountains on the Cameroonian border on September 5 and 30.[189] ISWAP retaliated in early October by killing a Boko Haram tax collector and fighters from Boko Haram’s Mandara Mountains–based Nglude faction.[190] This sparked a cycle of retaliatory clashes over the next month, including the assassination of Boko Haram’s second in command on October 27.[191]

Figure 26. Boko Haram and ISWAP Infighting Escalates in Northwestern Nigeria

Source: Miles Charles.

Fighting shifted north to both groups’ core support zones in the Lake Chad Basin in November. Boko Haram seized up to 8 ISWAP encampments in the Lake Chas Basin and killed dozens of ISWAP fighters in a complex assault from November 5 to 8.[192] ISWAP recaptured several Lake Chad Basin Camps on November 7 and launched two large-scale attacks on November 9 to recapture the remaining camps, but the Bakura faction repelled the assault.[193] Both groups mobilized a significant number of fighters toward the Lake Chad Basin in the following days.[194]

ISWAP defeating Boko Haram would strengthen the entire IS network in West Africa. ISWAP has lost thousands of fighters in clashes with Boko Haram since 2016.[195] Defeating Boko Haram would allow ISWAP to move into Boko Haram controlled territory in the Lake Chad Basin and Cameroon-Nigeria border, increasing its taxable population and operational freedom.[196]

ISWAP is already strengthening ties with IS Sahel Province. The UN has reported since 2024 that cells in southwestern Niger have linked the two Islamic State affiliates.[197] These cells are coordinated by the head of the al Furqan office and facilitate the movement of ISWAP weapons, fuel, equipment, and fighters to support IS activity in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali.[198]

Northwestern Nigeria

Nigerian forces arrested two prominent Salafi-jihadi leaders of Salafi-jihadi splinter cells across Nigeria, which may temporarily degrade the Salafi-jihadi network in northwestern Nigeria. Nigerian forces announced that security forces arrested high-ranking Salafi-jihadi leaders Mahmud Muhammed Usman and Mahmud al Nigeri, known as Abu Bara’a and Mallam Mahmuda, respectively.[199] Bara’a and Mahmuda were high-ranking leaders within Ansaru and Darul Salam, two Salafi-jihadi splinter groups based in the Kainji reserve that have fluid ties to different groups using the reserve as a sanctuary.[200] Individual leaders and human networks play an outsized role in shaping these connections and navigating tensions that emerge, which means that their arrests will likely affect these relationships.

You can read about Salafi-jihadi activity in northwestern Nigeria as part of the Sahel section here.

[1] https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/

[2] https://docs.un.org/en/S/2024/556

[3] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-may-15-2025-jnim-seizes-burkinabe-capital-blow-to-traore-iswap-advantage-in-lake-chad-is-sahel-operationalizes-nigeria-tripoli-clashes#LakeChad

[4] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/salafi-jihadi-ecosystem-in-the-sahel/; https://ecfr.eu/special/sahel_mapping/ansar_al_din

[5] https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ_French/journals_E/Volume-06_Issue-3/spet_e.pdf

[6] https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/operation-barkhane-success-failure-mixed-bag

[7] https://africacenter.org/publication/puzzle-jnim-militant-islamist-groups-sahel/

[8] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/how-ansar-al-islam-gains-popular-support-in-burkina-faso

[9] https://acleddata.com/report/jamaat-nusrat-al-islam-wal-muslimin-jnim

[10] https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining-extremism-jamaat-nasr-al-islam-wal-muslimin; https://acleddata.com/report/jamaat-nusrat-al-islam-wal-muslimin-jnim

[11] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/mali/306-mali-enabling-dialogue-jihadist-coalition-jnim; https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/2022/05/04/we-accept-save-our-lives-how-local-dialogues-jihadists-took-root-mali

[12] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/salafi-jihadi-ecosystem-in-the-sahel/

[13] https://x.com/TomaszRolbiecki/status/1506397624022278150

[14] https://newlinesinstitute.org/nonstate-actors/isis-in-africa-the-end-of-the-sahel-exception/

[15] https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-end-of-the-sahelian-anomaly-how-the-global-conflict-between-the-islamic-state-and-al-qaida-finally-came-to-west-africa/; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-al-qaeda-linked-militants-take-control-in-northern-mali

[16] https://apnews.com/article/mali-islamic-state-alqaida-violence-un-e841e4d5835c7fa01605e8fd1ea03fcf; https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2022/08/15/france-completes-military-pullout-from-mali_5993649_5.html

[17] https://www.dw.com/en/sahel-based-terror-groups-expand-to-coastal-west-africa/a-74639302; https://timbuktu-institute.org/media/attachments/2025/05/16/raport-jnim-threat-in-the-tri-border-area-of-mali-mauritania-and-senegal.pdf

[18] https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/the-underestimated-insurgency-african-states-at-risk-for-salafi-jihadi-insurgencies/; https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/african-studies-review/article/abs/climate-change-and-conflict-in-the-western-sahel/311BE9E1F1436AB3DB92763FA1B0B1DC; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/how-ansar-al-islam-gains-popular-support-in-burkina-faso

[19] https://x.com/almouslime/status/1964698727530233989; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250906-les-routiers-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9galais-captur%C3%A9s-par-le-jnim-au-mali-ont-%C3%A9t%C3%A9-lib%C3%A9r%C3%A9s; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250907-mali-attaque-%C3%A0-mopti-poursuite-du-blocus-jihadiste-%C3%A0-kayes-et-citernes-incendi%C3%A9es-%C3%A0-sikasso

[20] https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/explore/treemap?exporter=group-1&importer=country-466&view=markets&startYear=2012&product=product-HS92-126; https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/explore/treemap?exporter=group-1&importer=country-466&view=markets&startYear=2012&product=product-HS92-126; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1985091000831000858

[21] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[22] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/10/21/mali-jnim-militants-fuel-blockade/; https://www.studiotamani dot org/189240-la-vente-de-carburant-par-bidons-interdite-a-kadiolo; https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1134246785402460&set=a.640887034738440; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1974414211544387865; https://www.studiotamani dot org/192241-nioro-interdiction-de-vendre-du-carburant-dans-des-bidons-ou-des-sachets

[23] https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tocta_sahel/TOCTA_Sahel_fuel_2023.pdf; https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Lyes-Tagziria-Lucia-Bird-Illicit-economies-and-instability-Illicit-hub-mapping-in-West-Africa-2025-GI-TOC-October-2025.v3.pdf

[24] Lyes-Tagziria-Lucia-Bird-Illicit-economies-and-instability-Illicit-hub-mapping-in-West-Africa-2025-GI-TOC-October-2025.v3.pdf

[25] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1975503837457965305; https://x.com/konate90/status/1975313542074060960; https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1728354/economie-entreprises/mines-au-mali-la-penurie-de-carburant-epee-de-damocles-pour-le-moteur-economique-du-pays/; https://www.maliweb dot net/economie/transport/bamako-le-carburant-se-rarefie-jusqua-trois-heures-dattente-dans-certaines-stations-3110011.html

[26] https://www.ecofinagency.com/news-industry/0910-49408-mali-fuel-crisis-deepens-as-jihadist-blockade-strangles-supply

[27] https://apnews.com/article/mali-jnim-fuel-blockade-schools-dc75c7ef62995c4f7a25ca4be4b4a07a; https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm2w0zpew0ko; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20251110-mali-les-écoles-ont-rouvert-après-deux-semaines-de-suspension; https://www dot aljazeera.com/news/2025/10/27/mali-shuts-schools-as-fuel-blockade-imposed-by-fighters-paralyses-country

[28] https://x.com/Wamaps_news/status/1982840101865439238; https://apnews.com/article/mali-militants-fuel-blockade-c69bee3048e5aa8181a0fb658fb3e20c; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20251104-mali-les-conséquences-du-blocus-sur-l-économie-et-le-quotidien-à-bamako

[29] https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/fuel-blockade-in-mali-raises-risk-of-atrocities-as-civilians-face-starvation-and-isolation; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1978896907175964806

[30] https://www.koaci.com/index.php/article/2025/10/23/mali/politique/mali-le-gouvernement-suspend-la-societe-diarra-transport-apres-une-video-du-jnim_191423.html

[31] https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250904-mali-les-jihadistes-du-jnim-impose-un-blocus-%C3%A0-kayes-et-nioro-des-proches-du-ch%C3%A9rif-de-nioro-enlev%C3%A9s; https://www.theafricareport.com/391764/al-qaeda-affiliate-sets-up-blockade-in-western-mali-to-weaken-junta; https://fr dot allafrica.com/stories/202510190045.html; https://www dot koaci.com/index.php/article/2025/10/23/mali/politique/mali-le-gouvernement-suspend-la-societe-diarra-transport-apres-une-video-du-jnim_191423.html; https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1964961256781251055

[31] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1981084426592289096; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1979290905912971420

[32] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1981084426592289096; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1979290905912971420

[33] https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20251014-embargo-jihadiste-sur-le-carburant-le-gouvernement-malien-rend-les-entreprises-responsables-de-la-p%C3%A9nurie; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20251022-mali-le-jnim-poursuit-son-offensive-le-premier-ministre-d%C3%A9nonce-une-tentative-de-d%C3%A9stabilisation

[34] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1990886026089521349; https://www dot maliweb.net/economie/petrole/hydrocarbures-le-nerf-vital-du-mali-sous-escorte-armee-3110882.html

[35] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1986100225887354978; https://www dot seneweb.com/en/news/Afrique/crise-du-carburant-au-mali-bamako-enthousiaste-apres-larrivee-dun-important-convoi-de-camions-citernes_n_472876.html; https://allafrica dot com/stories/202510300359.html ; https://www dot fides.org/en/news/76976-AFRICA_MALI_Fuel_war_spreads_to_the_Capital_Bamako; https://apanews dot net/mali-announces-major-reshuffle-of-top-military-command/ https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1986100225887354978

[36] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c20e2lnvgpgo; https://x.com/aeowinpact/status/1983847083548537319; http://news dot abamako.com/h/302641.html

[37] https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20251020-voile-obligatoire-dans-les-transports-les-maliennes-pourront-elles-d%C3%A9sob%C3%A9ir-aux-jihadistes-du-jnim; https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/10/21/mali-jnim-militants-fuel-blockade/

[38] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1979290905912971420; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1980011260843528518; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20251020-voile-obligatoire-dans-les-transports-les-maliennes-pourront-elles-d%25252525C3%25252525A9sob%25252525C3%25252525A9ir-aux-jihadistes-du-jnim; https://x.com/konate90/status/1979660002521399573; https://www.20minutes.fr/monde/4180433-20251020-mali-groupe-djihadiste-exige-port-voile-separation-entre-hommes-femmes-transports?at_medium=display&at_campaign=149; https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/10/21/mali-jnim-militants-fuel-blockade/

[39] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[40] https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1702706/politique/mali-ce-que-lon-sait-de-lattaque-inedite-du-jnim-contre-kayes-et-plusieurs-villes-de-louest/

[41] https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1702706/politique/mali-ce-que-lon-sait-de-lattaque-inedite-du-jnim-contre-kayes-et-plusieurs-villes-de-louest/

[42] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[43] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[44] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[45] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[46] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[47] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[48] https://timbuktu-institute.org/media/attachments/2025/05/16/raport-jnim-threat-in-the-tri-border-area-of-mali-mauritania-and-senegal.pdf

[49] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[50] https://timbuktu-institute.org/media/attachments/2025/05/16/raport-jnim-threat-in-the-tri-border-area-of-mali-mauritania-and-senegal.pdf

[51] https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/ocwar-t-report-13-eng.pdf; https://issafrica.org/iss-today/timber-logging-drives-jnim-s-expansion-in-mali; https://timbuktu-institute.org/media/attachments/2025/05/16/raport-jnim-threat-in-the-tri-border-area-of-mali-mauritania-and-senegal.pdf

[52] https://www.spglobal.com/market-intelligence/en/news-insights/research/arrest-of-suspected-islamists-in-eastern-senegal

[53] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[54] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[55] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[56] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[57] https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2025-10/XCEPT-Report_Life-on-the-line_Chapter-4.pdf

[58] https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2025-10/XCEPT-Report_Life-on-the-line_Chapter-4.pdf

[59] https://apnews.com/article/mali-militants-fuel-blockade-c69bee3048e5aa8181a0fb658fb3e20c

[60] https://wits.worldbank.org/CountrySnapshot/en/MLI/textview

[61] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[62] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/Côte-divoire/b192-keeping-jihadists-out-northern-Côte-divoire; https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2025-10/XCEPT-Report_Life-on-the-line_Chapter-4.pdf

[63] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/Côte-divoire/b192-keeping-jihadists-out-northern-Côte-divoire

[64] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/Côte-divoire/b192-keeping-jihadists-out-northern-Côte-divoire; https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2025-10/XCEPT-Report_Life-on-the-line_Chapter-4.pdf

[65] https://www.africansecurityanalysis.org/reports/strategic-analysis-report-cross-border-security-threats-in-west-africa

[66] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-the-sahel

[67] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-march-22-2024-niger-cuts-the-us-jnim-encroaches-on-guinea-al-shabaab-hotel-attack#Mali; https://timbuktu-institute.org/media/attachments/2025/05/16/raport-jnim-threat-in-the-tri-border-area-of-mali-mauritania-and-senegal.pdf

[68] https://www.caasimada dot net/al-shabaab-oo-shaaciyey-magaca-iyo-beesha-ninkii-isku-qarxiyey-albaabka-hotel-syl

[69] https://www.theafricareport.com/67261/in-the-sahel-terrorists-are-now-sitting-at-the-negotiation-table/; https://x.com/Walid_Leberbere/status/1909554161298841719;https://x.com/Walid_Leberbere/status/1909546669269541124; https://www.dw.com/fr/au-mali-le-blocus-l%C3%A9r%C3%A9-lev%C3%A9/a-71290420; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250403-mali-les-dessous-de-la-lev%C3%A9e-du-blocus-jihadiste-de-boni; https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1735378/politique/au-mali-la-milice-dan-na-ambassagou-tente-de-survivre-en-simposant-par-la-peur/

[70] https://acleddata.com/report/hunters-militias-militarization-dozos-mali

[71] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[72] https://www.africansecurityanalysis.org/updates/burkina-faso-renewed-jnim-offensive-in-soum-province

[73] https://x.com/tweetsintheME/status/1921902097705955630; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-may-15-2025-jnim-seizes-burkinabe-capital-blow-to-traore-iswap-advantage-in-lake-chad-is-sahel-operationalizes-nigeria-tripoli-clashes

[74] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1987258720171270516; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1987263363924066403; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1989066745165017319; https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1988564680445481076

[75] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1987496192113021262; ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[76] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1987914813960315105

[77] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1987914813960315105; https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/09/15/burkina-faso-islamist-armed-groups-massacre-civilians

[78] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1988613348527591704

[79] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool; https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1937649252387152023; https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1941838321463796210; https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1942729065762345018; https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1942729065762345018; https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1943270342073483685; https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1943236753151922335; https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1943380797966159994; https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1943642546250350903; https://x.com/CEENASA396971/status/1943728642267156544

[80] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[81] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[82] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[83] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[84] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[85] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[86] https://www.africansecurityanalysis.org/updates/burkina-faso-renewed-jnim-offensive-in-soum-province

[87] https://x.com/tweetsintheME/status/1921902097705955630; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-may-15-2025-jnim-seizes-burkinabe-capital-blow-to-traore-iswap-advantage-in-lake-chad-is-sahel-operationalizes-nigeria-tripoli-clashes%2523_ednb31c90bfc4ff9436d030a928920db9b809c2e2ebb7cfc2a873cfbe806c479194340416e4a1f4a5f896f149fefa79062e7

[90] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1983584577030341000

[91] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1990123743138484661?s=20

[92] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1983584577030341000

[93] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[94] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[95] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[96] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool; https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-the-sahel

[97] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com

[98] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[99] https://www.france24.com/fr/afrique/20250121-otages-sahel-espagnol-libere-remis-autorites-algeriennes-rebelles-fla; ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool; https://x.com/Wamaps_news/status/1896230071263797655

[100] https://malijet dot com/actualite-sur-afrique/299915-niger--11-militaires-tues-dans-une-embuscade-pres-de-la fontier.html; https://x.com/ighazer/status/1895922654034440349; https://x.com/Wamaps_news/status/1896230071263797655

[101] https://x.com/Wamaps_news/status/1896230071263797655

[102] https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n22/394/29/pdf/n2239429.pdf?OpenElement; https://libyasecuritymonitor.com/aqim-uses-southern-libya-to-transport-fighters-to-mali-un-report/

[103] https://thearabweekly dot com/morocco-foils-terrorist-plot-targeting-security-sites-arrests-isis-linked-suspects; https://apnews.com/article/morocco-islamic-state-sahel-plot-2eed405c45bd6dc068fe31b25f76315e

[104] https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/islamic-state-march-africa; https://www.moroccoworldnews dot com/2023/10/358411/moroccos-bcij-arrests-4-isis-affiliated-suspects; https://www.moroccoworldnews dot com/2024/01/360459/moroccos-bcij-dismantles-four-member-isis-cell; https://www.moroccoworldnews dot com/2024/02/361097/moroccos-bcij-arrests-isis-affiliated-suspect-near-rabat

[105] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[106] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[107] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[108] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[109] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[110] https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Cross-border_road_corridors.pdf; https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/466461626746452108/pdf/Burkina-Faso-Niger-and-Togo-Lome-Ouagadougou-Niamey-Economic-Corridor-Project.pdf; https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/120971576492235825/pdf/Enhancing-Burkina-Faso-Regional-Connectivity-An-Economic-Corridor-Approach.pdf

[111] https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Cross-border_road_corridors.pdf; https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/466461626746452108/pdf/Burkina-Faso-Niger-and-Togo-Lome-Ouagadougou-Niamey-Economic-Corridor-Project.pdf; https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/120971576492235825/pdf/Enhancing-Burkina-Faso-Regional-Connectivity-An-Economic-Corridor-Approach.pdf

[112] https://riskbulletins.globalinitiative.net/wea-obs-006/03-jnim-consolidated-its-presence-in-the-central-sahel-in-2022.html; https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2025/cattle-wahala/; https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tocta_sahel/TOCTA_Sahel_Gold_v5.pdf; https://issafrica.org/iss-today/breaking-terrorism-supply-chains-in-west-africa

[113] https://www.wathi.org/laboratoire/choix_de_wathi/non-state-armed-group-and-illicit-economies-in-west-africa-jamaat-nusrat-al-islam-wal-muslimin-jnim-global-initiative-against-transnational-organized-crime-and-acled-october-2023/

[114] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/niger/b172-murder-tillabery-calming-nigers-emerging-communal-crisis;%20https:/www.aei.org/articles/one-year-after-nigers-coup/

[115] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[116] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[117] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[118] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-the-sahel#NWNiger

[119] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/06/24/niger-plusieurs-villageois-tues-dans-une-attaque-pres-des-frontieres-du-burkina-et-du-mali_6615600_3212.html; https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/06/24/niger-plusieurs-villageois-tues-dans-une-attaque-pres-des-frontieres-du-burkina-et-du-mali_6615600_3212.html

[120] https://x.com/WerbCharlie/status/1953038477961941474; https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1953035358842548414; https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250806-niger-avec-garkouwar-kassa-le-m62-veut-former-une-milice-civile-pour-appuyer-les-forces-de-sécurité; https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/08/08/le-niger-cree-une-milice-patriotique-pour-combattre-les-groupes-djihadistes_6627465_3212.html

[121] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/08/08/le-niger-cree-une-milice-patriotique-pour-combattre-les-groupes-djihadistes_6627465_3212.html

[122] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/niger/b172-murder-tillabery-calming-nigers-emerging-communal-crisis; https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/niger/289-sidelining-islamic-state-nigers-tillabery

[123] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/niger/b172-murder-tillabery-calming-nigers-emerging-communal-crisis; https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/niger/289-sidelining-islamic-state-nigers-tillabery

[124] https://acleddata.com/profile/volunteers-defense-homeland-vdp; https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/burkina-faso/313-armer-les-civils-au-prix-de-la-cohesion-sociale

[125] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[126] https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/burkina-faso/313-armer-les-civils-au-prix-de-la-cohesion-sociale; https://www.clingendael.org/publication/volunteers-defense-homeland;%20https:/acleddata.com/2024/03/26/actor-profile-volunteers-for-the-defense-of-the-homeland-vdp; https://africacenter.org/spotlight/understanding-fulani-perspectives-sahel-crisis; https://ctc.westpoint.edu/answers-from-the-sahel-wassim-nasr-journalist-france24-on-his-interview-with-deputy-jnim-leader-mohamed-amadou-koufa; https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/13/mali-jnim-fulani-tuareg-islamist-militancy-katiba-macina

[127] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[128] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[129] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[130] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[131] https://minorityrights.org/communities/fulani/

[132] https://www.hudson.org/sahelian-or-littoral-crisis-examining-widening-nigerias-boko-haram-conflict

[133] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[134] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[135] https://docs.un.org/en/S/2024/556

[136] https://docs.un.org/en/S/2024/556

[137] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[138] https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2024/dangerous-liaisons/; https://www.hudson.org/sahelian-or-littoral-crisis-examining-widening-nigerias-boko-haram-conflict

[139] https://x.com/BrantPhilip_/status/1944154124683292745

[140] https://x.com/MENASTREAM/status/1983974937405878456

[141] https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/uae-regionalization-sudan-war-jnim-expands-benin-nigeria-gulf-of-guinea-mali-sahel-mining-tuareg-fla-africa-corps-shabaab-shabelle-mogadishu-offensive-africa-file-june-2025; https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerian-military-warns-new-militia-threat-niger-mali-2024-11-07/; https://www.hudson.org/sahelian-or-littoral-crisis-examining-widening-nigerias-boko-haram-conflict; https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2024/dangerous-liaisons/

[142] https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/conflict-in-the-penta-border-area-1.pdf; https://www.criticalthreats.org/briefs/africa-file/africa-file-salafi-jihadi-groups-may-exploit-local-grievances-to-expand-in-west-africas-gulf-of-guinea

[143] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[144] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[145] https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/202507/PP_2425%20%28Niccola%20Milnes%20%26%20Rida%20Lyammouri%29_0.pdf

[146] https://www.military.africa/2025/02/the-rise-of-drone-warfare-insurgents-and-terrorists-in-africa/; https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhambling/2023/08/16/could-small-drones-really-replace-artillery/

[147] https://x.com/brantphilip1978/status/1952726009280647306

[148] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[149] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[150] ACLED database, available at https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool

[151] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/explaining-the-emergence-of-boko-haram/

[152] https://mappingmilitants.org/profiles/boko-haram; https://www.france24.com/en/20090730-nigerian-islamic-sect-leader-mohammed-yusuf-killed-detention-

[153] https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/06/10/anatomy-of-a-boko-haram-massacre/

[154] https://www.cnn.com/2014/04/15/world/africa/nigeria-girls-abducted/index.html

[155] https://www.voanews.com/a/boko-haram-claims-responsibility-for-bombing-in-nigerian-capital/1897973.html; https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2012/2/17/federal-prison-stormed-in-nigeria

[156] https://www.jstor.org/stable/27073436?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents

[157] https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/10/intl_tv/pham-boko-haram-isis

[158] https://www.wsj.com/articles/behind-boko-haram-s-split-a-leader-too-radical-for-islamic-state-1473931827

[159] https://guardian.ng/news/scores-die-in-iswap-boko-haram-clash/

[160] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57378493

[161] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/boko-haram-fighters-pledge-islamic-state-video-worrying-observers-2021-06-27/; https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/23/world/africa/boko-haram-surrender.html