Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Africa File: Islamic State Prison Break Signals Expanding Salafi-Jihadi Threat in Nigeria

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

To receive the Africa File via email, please subscribe here.

Key Takeaway: The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) freed dozens of Salafi-jihadi militants in an attack on a prison in Nigeria’s capital region on July 5. This incident is ISWA’s first claimed attack in the capital region and its most sophisticated attack outside of northeastern Nigeria. It likely required cooperation with other armed factions. The prison break indicates that the Salafi-jihadi threat is growing outside of northeastern Nigeria—jihadists’ main area of operations in recent years—and that Nigeria’s multifaceted security crisis is allowing Salafi-jihadi groups to expand.

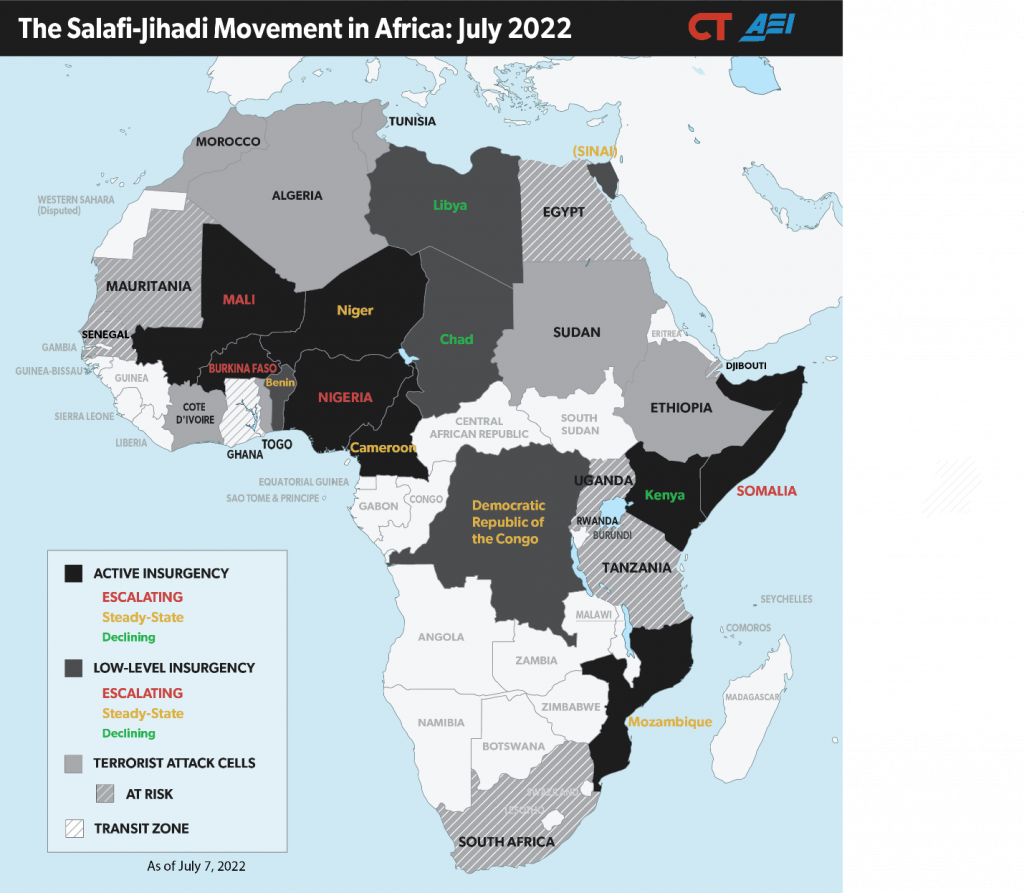

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: July 2022

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

Militants attacked a prison in Nigeria’s capital region on July 5, freeing hundreds of inmates, including dozens of jihadists. Three groups of attackers breached Kuje Medium -Security Prison in the Nigerian Federal Capital Territory (FCT) with at least three improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and small arms. The attack freed over 400 inmates, including 68* jihadists. The attackers retreated after fighting for about an hour and delivering a 15-minute sermon. Nigerian authorities reported hours later that security forces had recaptured* 443 escaped inmates and that 443 remained at large, including the escaped jihadists.*

ISWA claimed responsibility for the attack. The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) claimed that its fighters freed “dozens” of prisoners in a text post published by the Islamic State–linked Amaq News Agency on July 6.[1] Amaq also released a short video on June 6 showing the attack’s aftermath.[2] Amaq’s access to this footage increases the likelihood that ISWA is indeed responsible for the attack.

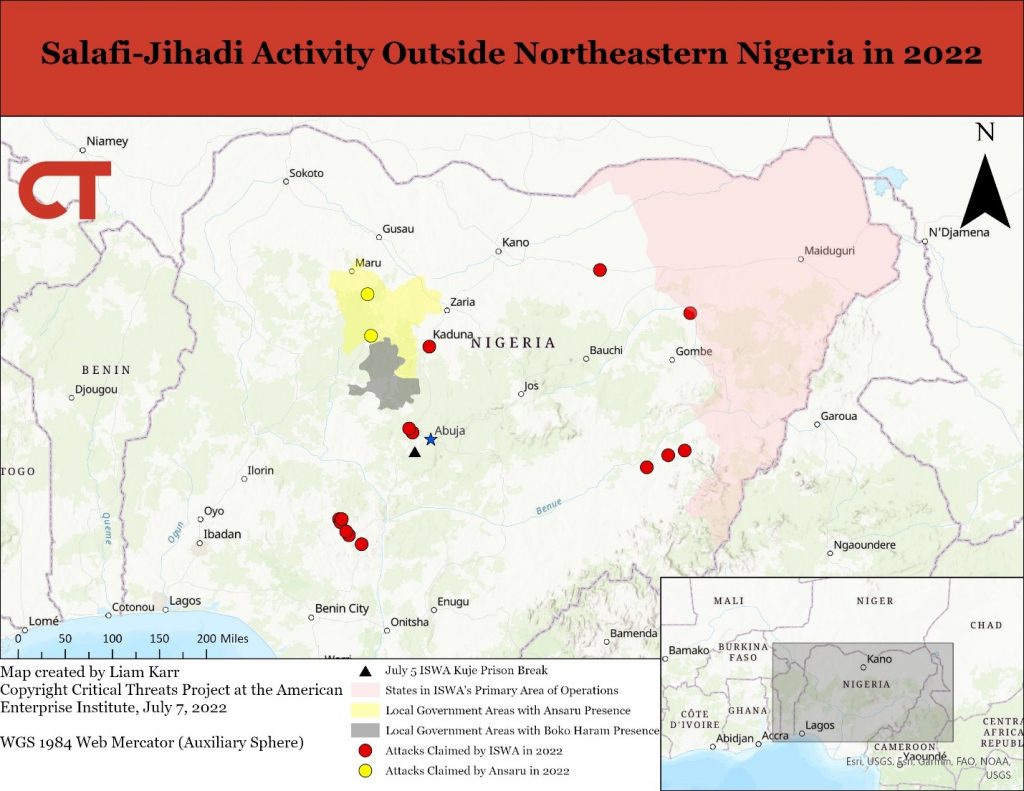

This prison break marks ISWA’s first complex attack far from its primary area of operations in northeastern Nigeria. ISWA has increased attacks outside of its primary haven in Borno State and its environs in 2022. These small-scale attacks in Niger* and Kogi* States, bordering the FCT, have involved small groups of gunmen or single IEDs, in contrast to the Kuje attack, which combined multiple IEDs and groups of gunmen. Prior attacks also targeted softer targets such as police stations and civilian gatherings. Militants may have raided police stations previously to gather weapons in preparation for the prison break. Nigerian officials claimed* that the Kuje prison attackers overwhelmed defending forces due to “superior weapons.”

Other Salafi-jihadi and criminal actors benefit from the prison break and may have cooperated with ISWA to conduct it. The July 5 attack freed veteran jihadists with ties to the al Qaeda–linked Ansaru group and Jama’at Ahl al Sunna lil Da’wa wal Jihad, known as Boko Haram.[3] The human networks that form these groups are heavily interconnected, and the relationships between Nigeria’s Salafi-jihadi factions have been in flux following the death of Boko Haram leader Abubakr Shekau in May 2021—creating opportunities for cooperation and reconciliation as well as competition. Several groups have potential motive or capability.

AK9 Hostage Takers. The perpetrators of a recent high-profile hostage-taking attack may have been involved in the prison break. Gunmen seized* dozens of hostages from the Abuja-Kaduna (AK9) train* in March 2022. Remnants of Boko Haram and a reclusive Islamist sect called Darul Salam likely participated in the AK9 attack and several others on the Abuja-Kaduna railway line. Recently released AK9 hostages report* that Kuje prison attackers and escapees returned to the camp where they were being held. The AK9 attackers have previously demanded* the release of “16 top commanders and sponsors in government custody,” indicating they may have had a motive to attack the prison. The AK9 attackers used IEDs to derail the train before boarding and seizing hostages. The Kuje attackers similarly used IEDs in a preliminary strike to breach the prison. ISWA did not claim the AK9 attack, though some outlets speculated* its involvement.

Boko Haram in Kogi. Preexisting Boko Haram networks in Kogi State could have participated in the attack. A Boko Haram cell in Kogi State freed hundreds of prisoners in two attacks in 2012 and 2014 and was building bombs* in the area. These networks may have reconstituted and regained these capabilities in Kogi. The Kuje attackers reportedly preached* to the prisoners in Ebira, a language most commonly found in Kogi State. The presence of attackers from Kogi could indicate cooperation between ISWA and Boko Haram remnants. It could also indicate that ISWA has absorbed Boko Haram defectors from Kogi or neighboring states. ISWA broke off from Boko Haram in 2015 and has reabsorbed Boko Haram fighters over time, especially since Shekau’s death.

Ansaru. Al Qaeda–linked Ansaru could have aided ISWA in the attack. Ansaru broke away from Boko Haram in 2012 and was active in Kogi State before going largely underground by 2014. Ansaru reemerged in northwestern Nigeria in 2019 and has infiltrated* local communities there. The group’s leader Khalid al Barnawi, whom security forces arrested in 2016, may be among* the Kuje escapees. Two Ansaru-linked Telegram channels discussed freeing Barnawi and other Ansaru preachers in 2020. ISWA-Ansaru cooperation has not been previously documented and would indicate that the groups’ overlapping human networks and shared interests are, at least temporarily, overcoming the larger Islamic State–al Qaeda rivalry.

Non-Jihadist Bandits. In a less likely scenario, ISWA could have also worked with bandit groups in the area or taken credit after bandits conducted the attack. Bandits have attacked prisons before, including freeing nearly 100 prisoners in Kogi State in September 2021. Jihadists and bandits have loosely collaborated when their interests aligned in the past. The Kuje escapees included bandits.* Several aspects of the Kuje attack make this cooperation unlikely, however. ISWA, unlike Boko Haram,* has never claimed an attack conducted by bandits. Bandits also usually choose targets with potential hostages or loot, but the Kuje attackers left behind high-value “VIP” prisoners.* Security forces also hold many high-profile bandits in other prisons, rather than in Kuje, because the Nigerian government did not classify bandits as terrorists until January 2022.

The Kuje prison attack is a significant propaganda win for ISWA and the Islamic State that builds on ongoing media and military campaigns. The attack followed an Islamic State media campaign that included videos from fighters in the Middle East praising its African affiliates in June.[4] The Islamic State also published several statements praising ISWA specifically and called for hijra (migration) to Africa as “a land of jihad.”[5] The Kuje attack provides more material to justify and amplify this messaging. The Islamic State may also be reviving a focus on prison breaks in 2022. ISIS conducted a large-scale prison break in Syria in January 2022. The Islamic State and ISWA had since used media released in April and June 2022 to urge fighters to focus on freeing captured militants.[6] Amaq highlighted the Kuje break as a “new operation of the famous ‘Breaking the Walls’” prison break campaign that al Qaeda in Iraq—ISIS’s predecessor—conducted in 2012–13. This reference to the Breaking the Walls campaign highlights the importance of the Kuje attack to the Islamic State organization and likely aims to frame it as a rallying cry for further prison attacks.[7]

The freeing of senior militants will affect Nigeria’s fractured jihadist landscape. Influential leaders, potentially including former Ansaru leader Khalid al Barnawi, could revitalize existing groups across the country. Veteran jihadists could use cross-group connections that predate the various schisms to facilitate interactions between groups in a dangerous scenario. Alternately, returning figures could exacerbate intra-jihadi tensions as they try to rebuild influence.

Nigeria faces a significant Salafi-jihadi threat outside of northeastern Nigeria for the first time since at least 2017, adding to multiple security crises as Nigeria enters an election period. ISWA and Ansaru have both increased activity in northwestern and central Nigeria in 2022, highlighting gaps in Nigeria’s security posture even as counterterrorism operations in Borno State reduce ISWA’s freedom of movement there. The Kuje attack demonstrates that ISWA could carry out future high-publicity attacks on hard targets or urban populations that have been insulated from terrorism. ISWA has an increased incentive to conduct such attacks as elections approach. Ansaru is widening its recruiting efforts and increasingly addressing national issues in its media. Salafi-jihadi expansion into new areas adds to instability in areas with heightened communal tensions or other armed militants that pose a more immediate and deadly* threat.* The Nigerian state’s inability to protect citizens has allowed armed groups to disenfranchise* citizens* by threatening to punish those involved in political activity. This could exclude thousands in the upcoming elections.

Nigerian officials may respond to the increased instability with measures that fuel communal violence that will ultimately benefit Salafi-jihadi and other armed groups in a dangerous situation. State officials in Zamfara State announced a plan* to arm civilians to protect themselves from bandit attacks. Arming civilians could increase communal violence and force civilians to rely on armed factions for protection. Ansaru has taken advantage* of similar circumstances to carve out its enclave in Kaduna State. The Kaduna State governor has considered* forcibly relocating citizens in villages linked to bandit groups. Forced relocations often create refugee flows that fuel insurgencies and increase the possibility of ethnic violence. Increased Salafi-jihadi attacks, especially on sensitive targets such as Kuje prison, increase the likelihood of heavy-handed government responses that exacerbate violence and increase armed groups’ control over local communities.

Figure 2. Salafi-Jihadi Activity Outside Northeastern Nigeria in 2022

Source: Author.

[1] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Takes Credit for Prison Break in Kuje, Near Nigerian Capital,” July 6, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] SITE Intelligence Group, “’Amaq Video Shows Initial Moments After Prisoners Freed in ISWAP Prison Raid in Kuje,” July 6, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[3] CTP uses “Boko Haram” to refer only to Jama’at Ahl al Sunna lil Da’wa wal Jihad.

[4] SITE Intelligence Group, “Like Their Brethren in Syria, IS Fighters in Iraq Encourage Counterparts in Africa in Video,” June 27, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[5] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Reinforces Africa as “Land of Immigration of Jihad” in Naba 343, Remarks on Parallels to Iraq and Syria,” June 20, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[6] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Incites Attacks on Saudi Prisons, Cites July 2015 Suicide Bombing Near al-Ha’ir Prison as Example to Follow,” July 1, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[7] SITE Intelligence Group, “IS Places Kuje Prison Break Within its Decade-Long “Demolishing the Fences” Campaign, Boasts Proximity to Nigerian Capital,” July 6, 2022, available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.