Africa File

The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.

October 16 Briefing

The US withdrawal from Syria will likely do catastrophic damage to America’s global leadership and value as an ally. It will also likely fast-track the Islamic State’s return in Syria and signal weakness that will embolden Salafi-jihadi militants globally. It has already energized US adversaries; Russian forces are currently backfilling American positions in northeastern Syria.

The American retreat from Syria has parallels in Africa. In Libya, the US has failed to support the internationally recognized government and US counterterrorism partner, the Government of National Accord (GNA). Forces led by would-be strongman Khalifa Haftar attacked the GNA in Tripoli in April 2019, torpedoing the UN-led peace process. Haftar’s forces, which have significant backing from regional states and Russia, are besieging many of the same militiamen who fought with US support against the Islamic State in Libya in 2016. The GNA has few options but to seek Turkish military support and Russian *mediation. Meanwhile, Salafi-jihadi militants are recruiting as the war drags on.

Russia’s potential kingmaking in Libya reflects greater ambitions. The Kremlin is expanding its influence in Africa to advance a number of strategic and grand strategic objectives. As Nataliya Bugayova and Darina Regio from the Institute for the Study of War argue, these objectives include expanding Russia’s military footprint, mitigating sanctions’ effects, and establishing a “network of geopolitical alliances and shared global information space” that positions Russia as a “revitalized great power” and challenger to the US-led world order. Vladimir Putin will host the first landmark Russia-Africa Summit in Sochi on October 23–24. Russia’s campaign in Africa endangers US security interests on the continent, among them counterterrorism objectives.

Any Kremlin effort dubbed counterterrorism should give us pause for two reasons. First, the Kremlin frequently uses counterterrorism as justification for establishing a military footprint that primarily serves other objectives and is not sufficient to conduct a counterterrorism mission. (See Syria.) Second, the Kremlin actually undermines counterterrorism objectives by enabling harsh crackdowns on vulnerable populations and strengthening repressive regimes, therefore worsening conditions that drive Salafi-jihadi insurgencies in the long term.

Russian engagement is increasing in three hubs of Salafi-jihadi activity in Africa (Libya, the western Sahel, and Nigeria) and Mozambique, where a Salafi-jihadi threat is emerging. This engagement is likely intended to develop demand in these countries for Russia’s military services and undermine a perception of the West as a reliable partner.

- Libya. The Kremlin is attempting to help Haftar’s forces break the stalemate in Tripoli by deploying private military contractors (PMCs) on the front line. Foreign support has yet to deliver a Haftar victory but is prolonging the conflict, causing mounting civilian harm and allowing Salafi-jihadi groups to operate and recruit. Russia’s interests in Libya include acquiring military basing or expanding access to Mediterranean naval facilities, casting itself as a peacemaker and alternative to the West, drawing neighboring Egypt away from the US, reactivating Qaddafi-era economic deals and securing new ones, and securing influence over hydrocarbon resources that in turn increase leverage over Europe.

- Western Sahel (Mali and Burkina Faso). Russia signed military cooperation agreements with Burkina Faso in 2018 and Mali in 2019. Sahelian governments and a Malian civil society group have appealed to Russia for security assistance. Funding and operational challenges for the regional G5 Sahel Joint Force, paired with indicators that Western countries—particularly the US and France—seek to draw down their footprint in West Africa, create favorable conditions for Russian influence to grow. Russia’s interests in the Sahel include securing access to natural resources.

- Nigeria. The Nigerian government seeks to purchase military aircraft and other materiel from Russia to pursue a militarized counterterrorism approach. The US has withheld the sale of light-attack aircraft to Nigeria due to human rights violations, an important condition that Washington upholds but the Kremlin does not. The Nigerian counterterrorism approach has harmed vulnerable populations and encouraged some communities to accept alternative governance from Salafi-jihadi groups. Russia’s interests in Nigeria—Africa’s most populous country—include establishing military cooperation and developing economic partnerships, notably for nuclear energy.

- Mozambique. The Kremlin is reportedly providing military equipment and training to Mozambican security forces attempting to counter a nascent Salafi-jihadi insurgency in the country’s north. This support will enable Mozambican forces to continue a counterproductive collective punishment approach that will enflame the insurgency over time. Russia’s interests in Mozambique include access to natural gas fields.

The Kremlin will continue to deliver more security help, such as limited deployments of PMCs and military advisers, to more African countries. It will amplify these limited investments with information campaigns. While Russia cannot deliver military or other aid on the scale of the West, it will leverage limited investments to gain influence over African countries’ decision-making to influence areas of core Russian interest, including military sales and security reach.

Nataliya Bugayova from the Institute for the Study of War contributed insight to this brief.

Figure 1. Overlapping Threats: Russian Security Cooperation and the Salafi-Jihadi Threat in Africa

Read Further On:

At a Glance: the Salafi-jihadi Threat in Africa

Updated October 16, 2019

Global counterterrorism efforts are rapidly receding with the end of counter–Islamic State operations in Syria and the withdrawal of US troops in October 2019. This withdrawal sets conditions for the rapid return of the Islamic State. It also damaged America’s reputation with current and potential counterterrorism partners wary of suffering the same fate as the abandoned Syrian Kurdish forces. The US administration also seeks to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan, a course that will likely be delayed rather than altered by the breakdown of talks with the Taliban. However, the Salafi-jihadi movement continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas in which previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement is positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations. The return of African Salafi-jihadists from prisons in Syria will likely accelerate these trends.

The Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, on the counteroffensive in Libya, and stalemated in Mali, Somalia, and Nigeria. However, conditions in the last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents over the next 12–18 months.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April, will continue to fuel the Salafi-jihadi comeback for at least the next several months, possibly allowing the Islamic State or al Qaeda to regain some of the territory they controlled before major operations against them from 2016 to 2019. The Islamic State’s comeback in Libya is part of its global effort to reconstitute capabilities after military defeats, an effort that the group’s leader, Abubakr al Baghdadi, sought to galvanize in a September audio message. Stalemates in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is rapidly eroding, and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in the eyes of their people.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness — such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown.

The Salafi-jihadi movement currently has four main centers of activity in Africa: Libya, Mali and its environs, the Horn of Africa, and the Lake Chad Basin. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other place is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse. Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the bases for future attacks against the US and its allies.

West Africa

Mali and Burkina Faso

The Salafi-jihadi movement is expanding more rapidly in the western Sahel than in any other African region as communal violence and state fragility spread. The movement’s epicenter in this region is Mali. Salafi-jihadi groups are active in the country’s north and have spread into the country’s center, where ethnic-based violence has increased in the past two years. Neighboring Burkina Faso is destabilizing rapidly as Salafi-jihadi groups take root in its north and east. Several Salafi-jihadi factions are cooperating, particularly in the Mali–Burkina Faso border area, to drive out security forces and establish themselves as the de facto governing power. The violence is causing a humanitarian crisis that includes retaliatory massacres of civilians in central Mali and mass displacement in Burkina Faso.

Large-scale Salafi-jihadi attacks are causing popular backlash against Sahel governments. Hundreds of Malians protested in the aftermath of near-simultaneous attacks on Malian Army and G5 Sahel Joint Force bases near the Burkinabe border on September 30, citing the government’s failure to deliver security and transparency. Attacks in Burkina Faso have also generated anti-government backlash. An August 29 attack on a Burkinabe army base harmed morale and stoked political jockeying. [See prior Africa Files for more on the September 30 attacks in Boulikessi and Mondoro, Mali, and the August 29 attack in Koutougou, Burkina Faso.]

Popular dissatisfaction with the Malian security response and the French intervention in Mali, the subject of recent protests, is creating an opportunity for greater Russian military involvement in Mali. A civil society organization called the “Malian Patriots Group” has made several petitions calling for Russian military support to resolve the deteriorating security situation in Mali. This latest petition follows the signing of a Russia-Mali security cooperation agreement in late June 2019.

Forecast: Russia will likely deliver security assistance to Mali in the coming year by either deploying PMCs or providing counterterrorism training. (As of October 16, 2019)

A Salafi-jihadi leader in central Mali announced a ceasefire with a rival militia that will bolster Salafi-jihadi governance credentials. Amadou Koufa, the leader of an al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)–aligned faction from the Fulani ethnic group, announced a cease-fire with the Dogon ethnic militia Dan Na Ambassagou, though its implementation is unclear. Koufa’s group has stoked ethnic violence in central Mali’s Mopti Region in recent years to delegitimize the state and present itself as the Fulani community’s defender.

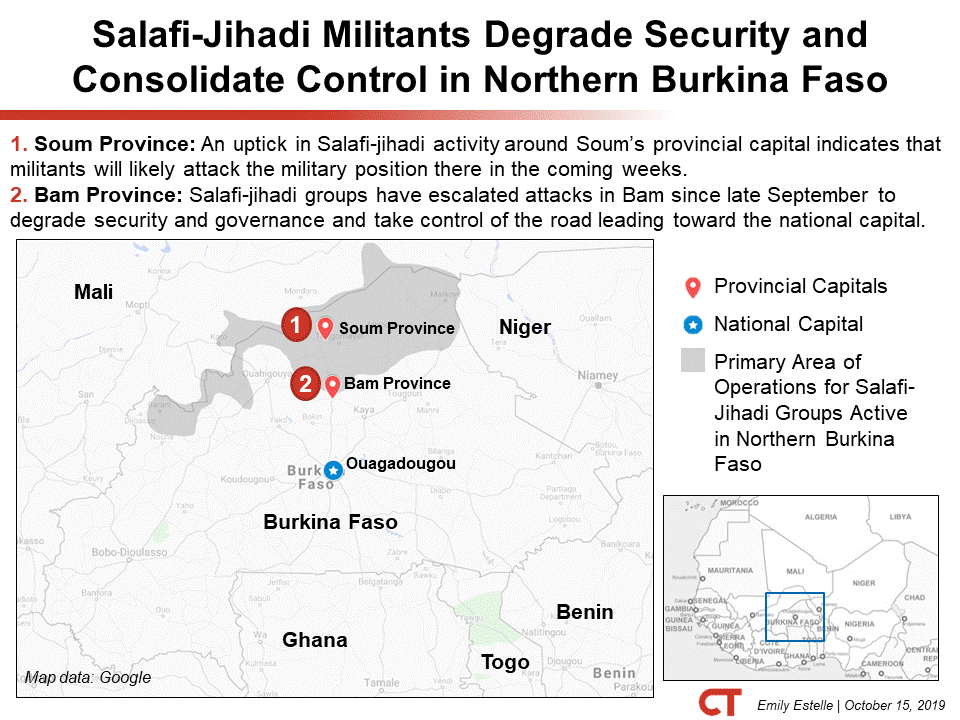

Salafi-jihadi militants in Burkina Faso are pursuing two major lines of effort to increase their freedom of movement and control over northern Burkinabe populations. (See Figure 2.) A cluster of Salafi-jihadi activity around Djibo, the capital of Soum Province, indicates that militants will likely mount an attack to drive out the remaining Burkinabe military presence in that region. Further south in Bam Province, Salafi-jihadi groups have nearly completely degraded the government’s authority and are now targeting local leadership and self-defense groups.

Figure 2. Salafi-Jihadi Militants Degrade Security and Consolidate Control in Northern Burkina Faso

Source: American Enterprise Institute

An unprecedented attack on a mosque in northern Burkina Faso may be intended to trigger retaliatory attacks. Unidentified attackers killed 15 worshippers in Salmossi in Oudalan Province in northern Burkina Faso on October 11. The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) may be responsible, as groups affiliated with al Qaeda generally eschew attacks on places of worship. However, this kind of attack would be unusual for ISGS. Militants began a campaign of attacks targeting Christians in Burkina Faso in 2019 and may be attempting to stoke confessional violence.

The death of senior Burkinabe Salafi-jihadi leaders may temporarily disrupt attacks in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. A reported raid may have killed the leader of Ansar al Islam, Jafar Dicko, and the group’s deputy leader Oumarou Bolly on October 1. Ansar al Islam may have participated in the September 30 attacks in Mali and has played a key role in the spread of the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in Burkina Faso since 2016.

Forecast: Salafi-jihadi militants will continue to take control of populations in northern Burkina Faso and may ultimately establish de facto governance in the area. They will likely mount a large assault on Djibo, the remaining Burkinabe military position in Soum Province, in the coming months to consolidate control. Militants based in Mali or Burkina Faso will attack tourist or Christian targets in Gulf of Guinea countries in the next 6–12 months. (Updated October 16, 2019)

Nigeria

A Salafi-jihadi insurgency is strengthening in the northeast of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country. The Nigerian government, despite repeated claims of victory, has ceded much of the remote northeast to militants, currently split into two main factions — the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWA) and Boko Haram — which also operate across Nigeria’s border in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. The Nigerian state is preoccupied with other domestic security and political challenges and is unlikely to rectify the conditions that led to Boko Haram’s formation and ISWA’s growth.

The Nigerian Army has adopted a new strategy of retreating to “super camps” and leaving militants unchallenged in the countryside. The official strategy is intended to concentrate well-armed and mobile fighting forces in fortified positions from which they can rapidly respond to militant activity. In effect, soldiers are withdrawing to fortress-like positions and allowing militants—who are often better armed than the army—to conduct unchallenged attacks on towns in Borno State in northeastern Nigeria. ISWA has temporarily seized several towns in Borno and Yobe States since the super camp strategy began and has featured these raids in its propaganda.

The new governor of Borno State approved mobilizing thousands of Nigerian hunters to fight Boko Haram and ISWA. Nigerian authorities prevented a similar operation five years ago. The hunters are intended to be more effective than the Nigerian military because of their knowledge of the local terrain. However, they may lack sufficient supply and armaments for the mission.

The Nigerian Army has cracked down on international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) after accusing them of aiding Boko Haram and ISWA. The army closed the offices of Action Against Hunger and Mercy Corps in late September. ISWA kidnapped and executed an Action Against Hunger employee in the same period. The closure of NGOs will harm local populations. The army’s role in these closures may cause further grievances against the state and encourage more communities to tolerate ISWA as an alternative source of governance.

The Nigerian government is seeking a military cooperation agreement with Russia that would allow it to intensify a counterproductive strategy against ISWA and Boko Haram. Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari will attend the Russia-Africa Summit in Sochi on October 23–24. He is seeking a technical cooperation agreement to acquire helicopters, tanks, and other materiel. Russia is an attractive partner for the Nigerian government because it does not attach human rights conditions to its arms sales. The Obama administration blocked the sale of light-attack aircraft to Nigeria following a 2017 strike on a displaced persons’ camp. Attacks on civilian populations undermine counterterrorism efforts by delegitimizing the Nigerian government and allowing Salafi-jihadi groups to present themselves as defenders of vulnerable communities.

Forecast: The withdrawal of Nigerian forces to super camps will allow ISWA to expand its governance in Borno State. ISWA’s focus on delivering governance in its areas of control has already convinced some civilians that ISWA provides a viable alternative to the largely absent Nigerian state. The Islamic State will use ISWA’s proto-state as evidence of success as it seeks to recover from military losses in Iraq and Syria. (Updated September 17, 2019)

North Africa

Libya

Russia increased military support for its preferred Libyan partner, Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), in an attempt to break the stalemate around Tripoli and resolve the Libya conflict in a way that favors Russian interests. Russian PMCs from the Wagner group joined LNA forces on the Tripoli front-line and have since suffered casualties. The reported presence of Russian aircraft at a Libyan airbase may indicate that official Russian military personnel are also present. The Kremlin seeks to position itself as a broker even while increasing support for the LNA.

Russia’s deputy foreign minister and Libya’s foreign minister *discussed the countries’ bilateral relationship and the upcoming Russia-Africa Summit on October 10. Russia’s interests in Libya include acquiring military basing or expanding access to Mediterranean naval facilities, casting itself as a peacemaker and alternative to the West, drawing neighboring Egypt away from the US, reactivating Qaddafi-era economic deals and securing new ones, and securing influence over hydrocarbon resources that in turn increase its leverage over Europe.

Haftar’s campaign, whether it succeeds or fails, will benefit the Salafi-jihadi movement in Libya. The LNA launched its offensive on Tripoli in April and has yet to breach the city’s defenses, even with significant support from Russia, the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, the civil war has destabilized parts of Libya where Salafi-jihadi militants are active, notably the far southwest. The Islamic State and AQIM have havens and access to smuggling and trafficking routes in this region and have attempted to recruit from local populations. The Islamic State’s increased recruitment in recent months necessitated a series of US airstrikes to curtail the threat in the past month. Even if Haftar succeeds, his methods—including an overly broad definition of who is a terrorist—will fuel a long-term Salafi-jihadi insurgency.

The UN-backed peace process in Libya remains stalled. Plans for a conference in Germany to resume this process have been delayed. The US is actively sustaining its partnerships with the GNA on the economy, development, and counterterrorism, but these are stopgap measures without a credible effort to end the civil war.

Forecast: The UN-led peace process in Libya is unlikely to succeed as Libyan factions and their foreign backers remain committed to military campaigns to secure their objectives. Russia will raise its profile as a potential broker and may attempt to facilitate a negotiated end to the conflict that secures its interests, particularly if Haftar’s offensive remains stalled. Separately, the Islamic State may attempt an attack in the coming weeks to prove its continued strength but will otherwise reduce its activity for several months while recovering from US strikes’ effects. The Islamic State will continue its recruitment efforts in southwestern Libya. (Updated October 16, 2019)

Tunisia

Counterterrorism operations have limited the ability of Salafi-jihadi groups to conduct attacks in Tunisia in the past several years. For example, militants failed to conduct attacks during two rounds of voting in Tunisia’s president elections in September and October despite threats. Grievances that feed Salafi-jihadi recruitment persist, however, and the potential for instability that could galvanize the Salafi-jihadi movement remains. Tunisia faces serious economic problems that its nascent democratic government has struggled to address.

Salafi-jihadi militants in Tunisia may be shifting to low-level individual attacks that require less coordination than past high-profile operations and bombings. A suspected Salafi-jihadi sympathizer killed a French national and injured a Tunisian soldier in a stabbing attack in Bizerte in northern Tunisia on October 14. This follows a similar “extremist” stabbing that killed a policeman and injured a soldier in Bizerte on September 23. A similar attack occurred in Tozeur in southwestern Tunisia earlier in September.

Tunisians selected their next president. Law professor Kais Saied will become the president of Tunisia following a decisive victory over media mogul Nabil Karoui in a run-off election. Saied is a political novice who has promised to improve Tunisia’s ailing economy and fight corruption.

Forecast: Leadership losses will prevent AQIM’s Tunisian affiliate from conducting an offensive attack during the Tunisian election season. Islamic State cells in Tunisia will attempt attacks in this same period and are more likely to succeed, but any attack will likely be unsophisticated. (Updated on September 17, 2019)

East Africa

Al Qaeda’s affiliate in East Africa, al Shabaab, is waging an insurgency in Somalia that threatens neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia. A stalemate is eroding in al Shabaab’s favor as African Union peacekeeping forces draw down ahead of their scheduled withdrawal in 2021. Al Shabaab seeks to expand its insurgency into Kenya and Ethiopia, in part as punishment for their participation in the peacekeeping mission.

The group also seeks to radicalize Muslim communities in Kenya and Ethiopia. Al Shabaab frequently attacks security forces in eastern Kenya and has conducted multiple high-profile attacks on soft targets in the country since 2013. Al Shabaab also recently plotted attacks in Ethiopia and may be seeking to increase its operations there. [For more on the Salafi-jihadi threat to Ethiopia, read the October 1 Africa File.]

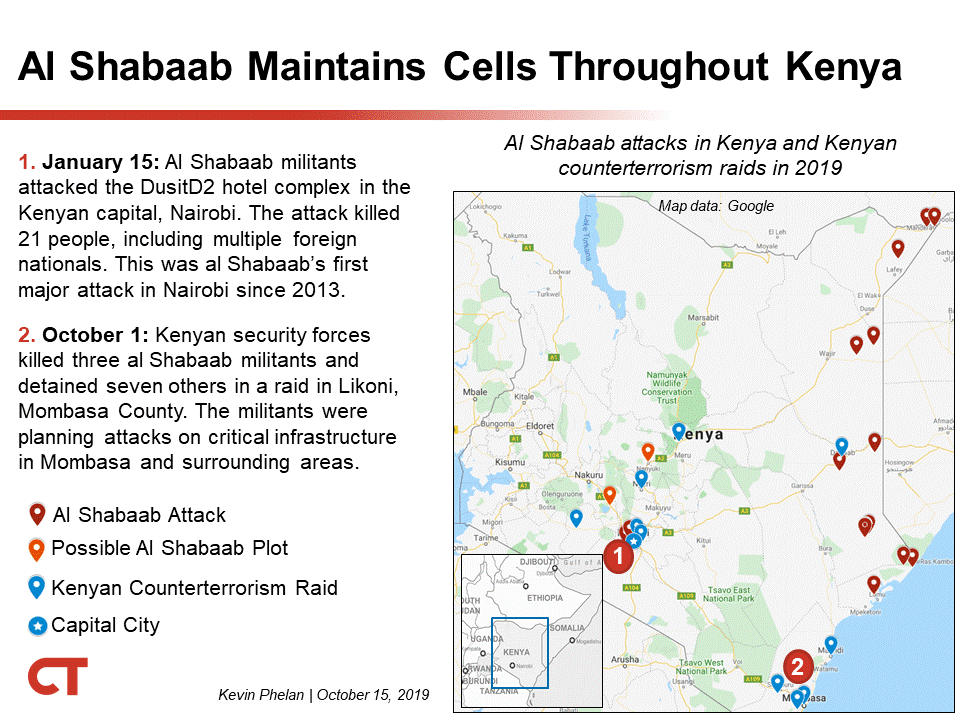

Al Shabaab attempted one of its most ambitious attacks ever along Kenya’s southern coast in October. Kenyan police foiled an al Shabaab plot in the port city of Mombasa on October 1. Police killed multiple al Shabaab suspects and arrested others days after police warned of an al Shabaab cell traveling from Somalia. The cell’s planned targets included Mombasa’s international airport, the Kenya Ports Authority headquarters, and a railway station. Al Shabaab recruits from Mombasa but has not conducted many attacks there since 2014.

Multiple al Shabaab cells in Kenya may have facilitated the plot. The suspects may have planned to use UN or police vehicles that al Shabaab militants had seized hundreds of miles away in northern Kenya. (See Figure 3.) The attackers had support from al Shabaab members in Mombasa who likely belong to multiple ethnic groups, underscoring al Shabaab’s ability to recruit across a wide spectrum of Kenyan society.

Al Shabaab likely intended the attack to galvanize Somalis and coastal Kenyan Muslims. Anti-Kenyan sentiment is currently high in Somalia in part due to a Kenyan-Somali maritime dispute. Al Shabaab’s emir released a rare speech in September accusing Kenya of stealing Somali territory and exploiting its natural resources. The planned attack in Mombasa would have struck a symbolic blow against East Africa’s largest port. Al Shabaab may have also sought to incite a harsh Kenyan crackdown on coastal Muslims. Kenya’s heavy-handed efforts to suppress al Shabaab along the coast between 2012 and 2014 alienated many coastal Muslims and helped al Shabaab recruit from those communities.

Forecast: Al Shabaab will attempt another high-profile attack along the Kenyan coast within the next 12 months and will activate cells for smaller, more frequent attacks in the area. Al Shabaab will continue recruiting from the coast while simultaneously expanding its recruitment among Muslim-minority communities in Kenya’s interior. (Updated October 16, 2019)

Figure 3. Al Shabaab Maintains Cells Throughout Kenya

Source: American Enterprise Institute