Africa File

The Africa File is an analysis and assessment of the Salafi-jihadi movement in Africa and related security and political dynamics.

Africa File: Al Qaeda’s East Africa affiliate will gain from US withdrawal, regional instability

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

Al Shabaab, al Qaeda’s East African affiliate, will benefit from the expected withdrawal of US troops from Somalia and growing instability in Somalia and neighboring Ethiopia. Al Shabaab is the most determined among al Qaeda’s African affiliates to conduct external terror attacks and has been developing increasingly lethal capabilities. Recent US actions have targeted al Shabaab’s bomb-making capability, including terrorist designations and a November raid in which an American CIA officer was killed. The withdrawal of US forces would derail the US-trained Somali special forces that have pressured al Shabaab’s leadership and reduced its most brazen and destructive terror attacks inside Somalia.

A US withdrawal now will contribute to instability in Somalia, as the country prepares for a fraught election cycle. Al Shabaab will attempt to disrupt the elections and their aftermath and may benefit from rising tensions between Somalia and Kenya. The group will likely benefit from the withdrawal of thousands of Ethiopian forces amid a security crisis in northern Ethiopia. Al Shabaab may also seek to expand into Ethiopia directly if the current conflict leads to fragmentation and more widespread violence.

In this Africa File:

- Ethiopia. The Ethiopian government’s claimed victory in Tigray region will not end the current conflict.

- Somalia. A political crisis in Somalia is raising tensions between Somalia and Kenya and will likely disrupt Somalia’s national elections.

- Mozambique. The Islamic State–linked insurgency in Mozambique is destabilizing the Mozambican-Tanzanian border region.

- Sahel. Salafi-jihadi groups are increasing their attack capability against security forces in northern Mali and escalating attacks in northern Burkina Faso.

- Lake Chad. Boko Haram escalated attacks on civilians in northeastern Nigeria.

Latest publications:

- Ethiopia. CTP is publishing frequent updates on the Ethiopia crisis. Sign up to receive the latest updates by email here. Read Jessica Kocan’s latest update here and Emily Estelle’s background on the conflict here.

- West Africa. Large-scale prisoner releases and escapes will invigorate the global Salafi-jihadi movement at a time when it has ample opportunity to expand. Recent prisoner exchanges, escapes, and mass releases are returning thousands of insurgents to battlefields in West Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia and will accelerate the growth of several insurgencies. Read more from Rahma Bayrakdar and the Institute for the Study of War’s Eva Kahan here.

Read Further On:

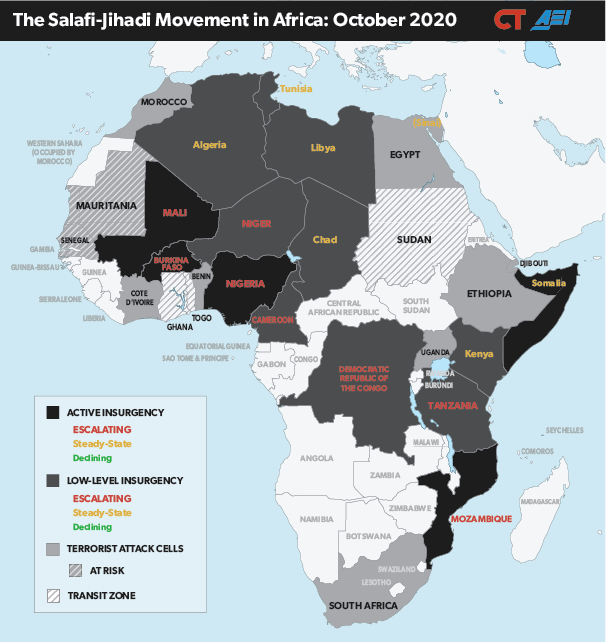

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: October 2020

View full image.

Source: Emily Estelle.

At a Glance: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated November 10, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic will hasten the reduction of global counterterrorism efforts, which had already been rapidly receding as the US shifted its strategic focus to competition with China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. This reduction will almost certainly include Africa. The US Department of Defense is considering a significant drawdown of US forces engaged in counterterrorism missions on the continent. The ongoing shift away from US engagement in the Middle East and Africa will likely continue after the change in presidential administrations in early 2021.

This drawdown is happening as the Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas where previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement was already positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure before the pandemic hit. Now, an increasingly likely wave of instability and government legitimacy crises will create more opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations.

The Salafi-jihadi movement is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali, where al Qaeda–linked militants are insinuating themselves into local governance while the Malian government is preoccupied with the aftermath of a coup. An Islamic State–linked insurgency has also developed rapidly in northern Mozambique and is spilling over into Tanzania. Ethiopia’s civil war, ignited in November 2020, will lift pressure from al Shabaab in Somalia and will likely create new opportunities for the Salafi-jihadi movement, particularly if the Ethiopian crisis becomes a prolonged regional conflict. Salafi-jihadi insurgencies are also stalemated in Nigeria and persisting amid the war in Libya. Current conditions—including mass anti-government protests in Nigeria and a fragile cease-fire in Libya—will likely evolve in the Salafi-jihadi movement’s favor in the coming year.

Counterterrorism efforts in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding in both host and troop-contributing countries and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in their people’s eyes. Mali’s coup and its aftermath will also disrupt international and regional counterterrorism efforts and coordination. Libya’s civil war, which has been subsumed by overlapping regional conflicts, will likely remain a simmering conflict that will fuel the conditions of a Salafi-jihadi comeback.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great-power competition, a move that coincides with efforts to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness—such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown.

The Salafi-jihadi movement has several main centers of activity in Africa: Mali and its environs, the Lake Chad Basin, the Horn of Africa, Libya, and now, northern Mozambique. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other places is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse (all now likely to be exacerbated by the pandemic). Local crises are incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the basis for future attacks against the US and its allies.

East Africa

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian government’s claimed victory in Tigray region will not end the current conflict. Federal forces seized the Tigray capital, Mekelle, from the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) on November 28. Fighting between the TPLF and federal forces has continued since. The TPLF will likely wage a long-term insurgency in an attempt to recapture Mekelle and prevent federal and allied forces from controlling Tigray region. TPLF leadership vowed to continue fighting federal troops. TPLF forces recaptured a town on a road toward Mekelle on November 29, indicating that the TPLF will attempt to isolate federal troops in the city. The TPLF is also building up forces within 30 miles of Mekelle.

A long-term TPLF insurgency in Tigray exacerbates the risk of Ethiopia’s fracturing. Fighting would likely spread to neighboring Amhara region. Amhara regional forces have backed the federal government in the conflict, which could revive a Tigray-Amhara land dispute. Continued fighting in Tigray could also heighten ethnic clashes in other Ethiopian regional states as federal troops deploy to Tigray. Such violence *occurred in Konso town in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s region in southwestern Ethiopia in mid-November after federal troops withdrew from the area, likely to support fighting in Tigray.

The Tigray conflict contributes to spreading instability in East Africa. Ethiopia is the world’s largest contributor of peacekeeping forces with deployments in Sudan, South Sudan, and Somalia. Ethiopian troops have withdrawn from Somalia and South Sudan due to fighting in Tigray. Somalia depends on foreign military support to combat the al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab. The Tigray conflict is also drawing in Eritrea, which has facilitated Ethiopian troop movements and may be *contributing forces to the conflict directly. The TPLF has fired rockets at Eritrea’s capital in retaliation.

The Tigray humanitarian crisis is growing. Over 45,000 Ethiopians have fled to Sudan since the conflict began. The fighting has also displaced some of the nearly 100,000 Eritrean refugees living in Tigray.

Forecast: The Tigray conflict will extend into 2021. A prolonged and simmering conflict is more likely than a decisive outcome. Prolonged conflict will gradually weaken Ethiopia’s institutions while encouraging unrest in other parts of the country, increasing the risks of fragmentation, secession, and foreign meddling. (As of November 10, 2020)

Somalia

A political crisis in Somalia is raising tensions between Somalia and Kenya, which will likely disrupt Somalia’s national elections. Gedo region, located in southwestern Somalia’s Jubbaland state and bordering Ethiopia and Kenya, is at the center of the current crisis. Ethiopian and Kenyan troops have been active in Gedo intermittently over the last 25 years.

Long-standing tensions between Jubbaland’s leadership, which Kenya backs, and the Somali Federal Government (SFG) have spiked over the course of 2020. SFG troops *seized two districts in Gedo in early February, inciting clashes with Kenyan-backed Jubbaland state forces in February and March 2020 that displaced more than 50,000 people. The clashes created a security vacuum that al Qaeda’s affiliate al Shabaab exploited. The Gedo regional governor *accused Kenyan forces of kidnapping innocent Somali civilians from the region under the guise of counterterror efforts in late September.

The current crisis centers on Somalia’s national elections with presidential elections set for February 2021 and parliamentary elections previously set for December now delayed. Somalia’s Foreign Affairs Ministry *dismissed Kenya’s ambassador to Somalia on November 29 on the accusation of pressuring Jubbaland’s president to renege on an agreement to hold elections in Gedo. Jubbaland’s president refuses to hold elections so long as the Somali National Army remains in the region.

The risk of renewed hostilities is high and will create opportunities for al Shabaab to attack, including in Kenya and possibly Ethiopia. Al Shabaab will take advantage of the security vacuum by staging attacks along the Kenyan-Somali border. The group regularly *targets civilians and *communication infrastructure in Kenya’s Mandera County as well as regional officials in Gedo. Militants *targeted one such official in Bardhere on November 12, according to pro–al Shabaab media. The further deterioration of Kenyan-Somali relations could also disrupt counterterrorism coordination to al Shabaab’s benefit. Al Shabaab may also seek new opportunities to attack in the Ethiopian-Somali border area after Ethiopian troops withdrew from Gedo in mid-November in response to the Tigray conflict in northern Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, al Shabaab remains capable of staging large-scale attacks in multiple areas of Somalia. Al Shabaab *raided a Somali military base in Mudug region in central Somalia on November 30. Separately, the group conducted a suicide vest attack at an ice cream parlor in the Somali capital on November 27.

Al Shabaab continues to develop its advanced bomb-making capability. The US Department of Sate designated two senior al Shabaab leaders, including explosives expert Abdullahi Osman Mohamed, as Specially Designated Global Terrorists on November 17. Al Shabaab has demonstrated an intent to attack internationally by training operatives to fly planes within the past year. An American CIA officer was killed in a raid targeting an al Shabaab bomb maker in November.

Mozambique

Cross-border activity continues to fuel the Islamic State–linked insurgency in Mozambique. Tanzanian police *arrested several people from western Tanzania’s Mwanza and Kigoma regions attempting to join the Islamic State affiliate in Mozambique on November 26. The national police chiefs of Tanzania and Mozambique *agreed to conduct joint operations to target militants in late November.

Counterterrorism efforts have not yet significantly weakened the group, however. Militants reentered northern Mozambique’s Muidumbe district in Cabo Delgado province on November 26 after government forces reoccupied the district on November 19. Islamic State–linked militants maintain control of a port in northern Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province.

Forecast: Salafi-jihadi militants may temporarily withdraw from Mocimboa port during a government offensive but will likely return to the area. Militants’ control of key roads and ability to conduct naval attacks will prevent the government from sustaining an effective military presence in the north. Brutal attacks on civilians will continue to drive already high displacement. (As of November 10, 2020)

West Africa

Sahel

An al Qaeda–linked group is developing its attack capability against security forces in northern Mali. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) conducted a coordinated attack against three separate French and Malian military camps and a UN base in northeastern Mali’s Gao, Kidal, and Menaka regions on November 30.[1] The attacks damaged a UN base but did not cause casualties. JNIM attacks Malian and international military bases frequently, but these operations were the first near-simultaneous attacks on multiple towns spanning a wide geographical area.[2]

The coordinated attacks signal resilience after French forces killed JNIM’s military commander Ba Ag Moussa in northeastern Mali earlier in November. French and Malian security forces have carried out several operations against JNIM throughout November.

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) demonstrated its continued capability following months of clashes with JNIM by increasing attacks on security forces in northern Burkina Faso. The ISGS, the Islamic State’s Sahel branch, is attacking security forces in Burkina Faso and along Burkina Faso’s border with Mali and Niger. ISGS claimed responsibility for an attack on Burkinabe security forces on November 11.[3] The attack killed 14 soldiers, making it the second-deadliest militant attack in Burkina Faso’s history. ISGS also released a video showing the execution of a Burkinabe soldier on November 18. The group conducted multiple attacks in northern Burkina Faso throughout November.

[Note: The Islamic State formally includes ISGS in its West Africa Province. ISGS is distinct from the Islamic State affiliate of the same name in the Lake Chad Basin.]

JNIM and ISGS continue to clash along Mali’s southern border. ISGS and JNIM began clashing with one another in late 2019, ending years of coexistence. This rivalry is an ongoing secondary effort for both groups. It appears that JNIM is maintaining a stronghold in northern and central Mali, while ISGS is focusing its efforts on the tri-border region connecting Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Islamic State and al Qaeda media have published several releases in an effort to present themselves as the stronger and more prominent group in the Sahel region.[4]

Forecast: JNIM will maintain its stronghold in northern Mali and continue to repel ISGS in Mali. Counterterrorism efforts will hinder but will not greatly weaken JNIM in Mali. ISGS will focus its efforts on gaining control in the tri-border region. ISGS will draw greater counterterrorism pressure than JNIM will because of its high-profile attacks. ISGS’s growth will be limited by the brutality of its strategy, however, which will draw local backlash and international attention. (As of December 3, 2020)

Lake Chad

The Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWA) is continuing attacks against security forces in the Lake Chad region. The ISWA claimed an improvised explosive device attack on a boat killing four Chadian soldiers and injuring several others on November 25. The group also ambushed a Nigerian army convoy killing 10 and wounding others in eastern Nigeria’s Borno State on November 22.[5] ISWA previously increased military campaigns in response to the Islamic State’s “Answer the Call” campaign, and the group is likely continuing this trend despite ongoing counterterrorism pressure.

ISWA abducted an aid worker and two local officials in Borno State on November 30. The officials were returning from Borno State’s first local council elections since 2009, a delay caused by the Boko Haram/ISWA insurgency. ISWA has attacked aid workers across West Africa throughout 2020. ISWA militants based in the Lake Chad Basin region raided a Red Cross office in southeastern Niger’s Diffa region on September 29. Attacks on aid workers may be intended to gain resources and fit a trend toward brutal propaganda from Islamic State affiliates in West Africa.

Boko Haram is attacking civilians to gain access to resources and prevent cooperation with security forces. Boko Haram militants killed 110 farmers in northeastern Nigeria’s Borno State on November 28 and claimed responsibility for the attack on December 1. The UN deemed the massacre the most violent attack against civilians this year. Suspected Boko Haram militants killed 22 farmers in separate attacks in October. The latest massacre appears to be a retaliatory attack by Boko Haram to prevent civilians from contacting security forces and terrorize them into compliance.

[1] “JNIM Reportedly Responsible for Coordinated Attacks on French Bases in Mali,” SITE Intelligence Group, November 30, 2020, full report available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] “JNIM Reportedly Attacks Malian Military Base Outside Bamako,” SITE Intelligence Group, August 5, 2020, full report available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[3] “ISWAP Claims Ambush on Burkinabe Soldiers in Oudalan, Killing 20,” SITE Intelligence Group, November 14, 2020, full report available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[4] “Pro-AQ Media Unit Follows-up on Alleged JNIM Projectile Attacks on French-EU Bases, Gives Map of Fighter Presence,” SITE Intelligence Group, December 1, 2020, full report available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[5] “ISWAP Claims Killing "Dozens" of Chadian Soldiers in Bomb Blast Targeting Boat, Clashes with Nigerian Troops and CJTF,” SITE Intelligence Group, November 23, 2020, full report available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.