{{currentView.title}}

April 05, 2023

Ending the US Presence in Syria Could Cause a Rapid ISIS Reconstitution and Threaten Core US National Security Interests

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader’s awareness.]

In a March 23 House Armed Services Committee hearing on the US Central Command’s force posture, Central Command Commander Gen. Michael Kurilla said ISIS will return within one to two years without a US presence in Syria. Kurilla said the US presence enables its principal counter-ISIS partner, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), to contain ISIS’s insurgency to a low level. ISIS’s insurgency today relies on assassinations of key figures, extortion of the population, and hit-and-run attacks against SDF positions, a sharp contrast from its strength during the territorial “caliphate” or its insurgency in Iraq from 2011 to 2014.[1] The Islamic State’s leadership controls its global affiliates from Syria. ISIS cells in Syria also plan external attacks against the West, including attacks using chemical and biological weapons.

ISIS is a viable insurgency that aims to restore a territorial “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria. ISIS retains the ability to execute decentralized insurgent campaigns and plan major attacks despite the SDF’s US-supported counter-ISIS efforts. ISIS’s campaigns and attacks aim to restore the territorial “caliphate.” ISIS uses its planning and attack capabilities to generate forces through prison breaks, carry out assassinations, and coerce civilian populations. These efforts aim to provide experienced fighters to improve ISIS’s capabilities and undermine the SDF by demonstrating the SDF’s inability to provide security to the population. The group also exerts physical and psychological control over some local populations through intimidation.

The SDF can contain ISIS with US support, but the SDF’s inability to fill capability gaps in logistics and intelligence collection and exploitation would cause it to fail to contain ISIS’s insurgency without US-provided logistics and intelligence. The Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) inspector general’s fourth quarter 2022 report said the SDF is only “moderately capable” and relies on the United States for intelligence and some targeting. These US-provided enabling functions allow the SDF to target ISIS leaders and prevent ISIS attacks. The OIR inspector general added that the SDF would be unable to sustain itself and would face logistics issues without US support, which would strain the SDF’s already-stretched bandwidth. The inspector general also said the SDF struggles to balance competing priorities.

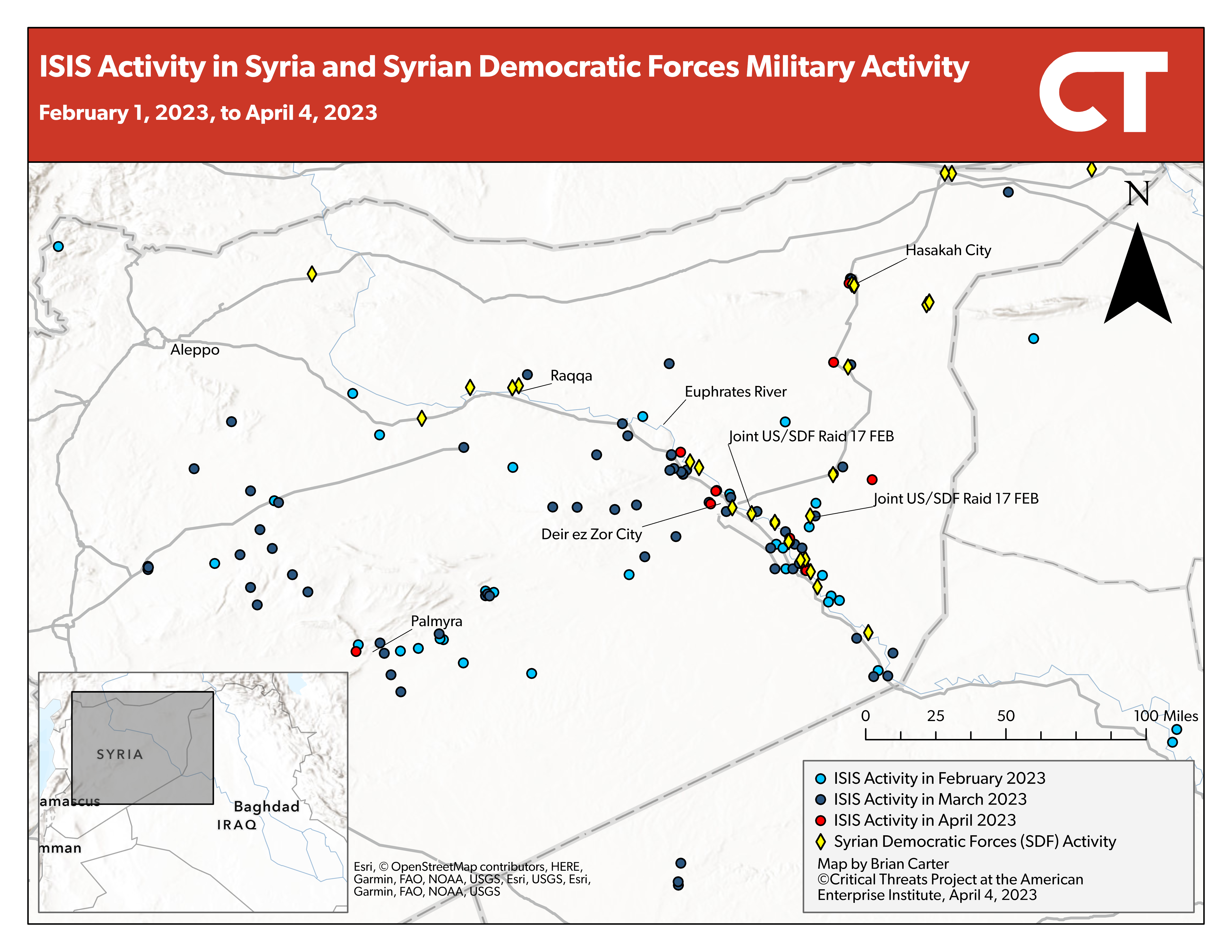

Figure 1. ISIS Activity in Syria and Counterterrorism Operations, February 1, 2023, to April 4, 2023

Source: Author’s research.

The SDF’s ethnic composition and counterinsurgency methods complicate working relationships with local populations, likely undermining the forces’ ability to collect and exploit human intelligence for counter-ISIS operations. The SDF is a Kurdish-dominated but multiethnic collection of militias. The Kurdish domination of the SDF causes friction with some Arab communities. Human intelligence capabilities in counterinsurgency are reliant on trust between the local population and the counterinsurgent force. The SDF relies on arbitrary arrests of innocent civilians and *sweeping *operations in Arab areas to target ISIS, undermining this trust. Local media often accuses the SDF of politically motivated arrests under the guise of *anti-ISIS operations. SDF fighters also frequently loot homes during sweeping operations and sometimes abuse or murder civilians. This causes extreme dissatisfaction with SDF rule, which creates opportunities for ISIS to exploit tribal or local disputes for its own gain by positioning itself as a protector of local communities.

CTP has not observed ISIS propaganda that aims to take advantage of these opportunities, but ISIS may be engaging local communities privately. ISIS assassinated a local Bakir tribal spokesperson after a local SDF-aligned military commander and Bakir tribesman’s brother murdered two Baqqara tribal women.[2]

The SDF deems multiple, competing threats more severe than ISIS and lacks the capacity to simultaneously counter these threats. Turkey views the SDF as an outgrowth of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (known as the PKK) and has repeatedly invaded northern Syria to create a buffer zone between the Turkish border and SDF-held territory. The OIR inspector general reported that the SDF becomes “rapidly overstretched” when Turkey threatens to invade northeastern Syria, which jeopardizes “counter-ISIS operations.” The SDF views ISIS as the least concerning threat and would subsequently de-prioritize it in the event of a US withdrawal. The SDF paused counter-ISIS operations with the United States in December 2022 amid Turkish threats, pointing to its concern with the Turkish threat.

Simultaneously, the Syrian regime and its Iranian partners seek to undermine SDF control in northeastern Syria by challenging SDF service provision and assassinating local leaders. Regime-backed sleeper cells maintain weapons depots in northeastern Syria, from which they conduct hit-and-run attacks targeting SDF and uncooperative local officials. The regime also seeks to extend its control over the remainder of Syria and could intensify its efforts to accomplish this objective in the event of a US withdrawal.

The regime is not a reliable counterinsurgency partner, and it will likely permit ISIS to expand to support its own objectives. The regime has contributed to the expansion of ISIS and its predecessors in Iraq and Syria since 2003. The regime facilitated the travel of foreign fighters into Iraq in the 2000s, where they joined al Qaeda in Iraq and attempted to undermine the Iraqi state. More recently, the regime began releasing hundreds of jihadists in 2011 as part of an effort to cast the Syrian uprising as a terrorist threat and justify an escalating crackdown against the Syrian people. The regime also released around 200 ISIS fighters in 2019 in Deraa province to eliminate future threats to the regime’s control of Deraa from reconciled opposition fighters. Local sources *accused the regime of releasing ISIS fighters to kill former opposition fighters.

The regime clearing operations in regime-held areas are ineffective and unlikely to improve, even with greater regime dedication to confronting ISIS. The regime relies on incompetent forces for anti-ISIS operations, because more effective and well-connected forces refuse to fight ISIS in the desert. Other pro-regime commanders cut local deals with ISIS to facilitate smuggling or kill local opponents. The regime’s anti-ISIS clearing operations usually consist of mounted militiamen driving through the desert. These operations do not disrupt ISIS freedom of movement, which would require regime forces to garrison the desert areas it frequently clears. ISIS fighters therefore quickly return to the “cleared” areas. Other regime clearing operations—such as those in Deraa province in late fall 2022—do not effectively *block ISIS leaders or cells from fleeing the area, allowing the group to reconstitute elsewhere.

ISIS senior leaders hide in plain sight and build refuge in regime-held Syrian territory, from which they could plan external attacks. Reconciled opposition militias killed the so-called ISIS caliph in Deraa province in October 2022, where he had *established a court and local *refuge in the town of Jassem, according to local sources. The so-called caliph’s location was *reportedly only 400 meters from a Syrian army checkpoint, suggesting the Syrian regime was unable or unwilling to dislodge the local ISIS presence. This local Syrian cooperation with ISIS is not rare. A US raid in October 2022 killed a senior ISIS official and captured several Syrian regime associates in regime-held northeastern Syria. This form of local or tacit support to senior ISIS leaders will improve their ability to find sanctuaries from which they can plan attacks against the West.

A withdrawal by the United States would strip the SDF of capabilities the force needs to contain ISIS and render it vulnerable to attacks from Turkey, Iran, and the Assad regime. The SDF would face challenges managing logistics to sustain itself, providing and exploiting intelligence to enable operations, and maintaining detention facilities holding ISIS fighters. The SDF may also face major desertions of Arab fighters without a US presence, weakening the organization as threats increase. The United States helped bind Arab militias to the SDF in 2015 and continues to support the group’s disparate factions to avoid fracturing. The Assad regime, Iran, Russia, and Turkey would likely intensify their efforts to undermine or destroy the SDF by attacking SDF positions and seizing oil fields, which represent a key SDF revenue source. Turkey may choose to invade or increase air strikes against the SDF in northeastern Syria without US presence.

ISIS is very likely to take advantage of reduced SDF capabilities to rapidly accelerate its plans to restore a territorial “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria. ISIS views its loss of the territorial “caliphate” as a temporary setback on its road to victory. ISIS has a well-developed strategic approach for restoring the territorial “caliphate,” and it is setting the conditions for that return. The group views its retreat into rural areas in Iraq and Syria as analogous to its period of reconstitution in Iraq between 2008 and 2010, when it developed a strategy to undermine local groups resisting ISIS’s return in Iraq.[3]

In the event of a US withdrawal, ISIS would reconstitute itself as a robust military organization with control over populations in northeastern Syria in less than 18 months. ISIS would likely accomplish this along four mutually reinforcing lines of effort. First, it would create sanctuaries free from SDF disruption. ISIS would create sanctuaries for itself by targeting SDF forces with improvised explosive devices and ambushes to deny the SDF access to certain areas.[4] ISIS would use these sanctuaries to rebuild key capabilities, like the production of vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices, while planning complex operations to free veteran fighters and commanders from detention facilities. Second, ISIS would eliminate local forces hostile to ISIS’s presence in northeastern Syria by identifying and targeting key leadership nodes. Then, the group would initiate a propaganda campaign highlighting ISIS’s “victory” over the United States to increase recruitment. Finally, ISIS would conduct prison breaks to generate forces and free veteran commanders. The 10,000 ISIS fighters in makeshift detention facilities in northeast Syria represent an “army-in-waiting” that ISIS will attempt to break out. The SDF will not be able to move these fighters into planned, purpose-built detention facilities without US support.

ISIS’s predecessor pursued a similar effort after the US withdrawal from Iraq in December 2011. The United States said only 800–1000 al Qaeda in Iraq supporters and 200 “hard-core fighters” remained in Iraq in November 2011—just over two years before ISIS’s dramatic seizure of Mosul, Iraq. Today, the UN assesses that 5,000–7,000 ISIS supporters, about half of whom are fighters, remain in Iraq and Syria, in addition to 10,000 fighters in detention facilities. Al Qaeda in Iraq rapidly reconstituted itself after the US withdrawal between 2011 and 2014 by freeing fighters from detention facilities, identifying and eliminating key individuals resisting its resurgence, and capitalizing on local grievances caused by a counterproductive Iraqi counterterrorism approach.

The SDF’s capacity and capability shortfalls would make it difficult for the SDF to limit ISIS’s ability to exert control over the population and create sanctuaries. ISIS already has secured a degree of coerced cooperation from the population through assassinations, executions, and pledges of loyalty.[5] The SDF’s trust deficit with the population would cause the force to struggle to find and eliminate key ISIS leaders taking refuge in these sanctuaries. Premier SDF units, such as its US-trained counterterrorism force, may be repurposed to target threats from regime sleeper cells or Turkey. The SDF redeployed other forces to address competing security concerns at the expense of the anti-ISIS effort in 2019. Premier SDF forces currently conduct raids targeting ISIS leadership and serve as a response force for detention facilities and Al Hol internally displaced persons camp. This would increase ISIS’s ability to target these facilities.

A reconstituted ISIS would be a major threat to the US homeland, the West, and the Middle East. ISIS retains the desire to attack the West, including the United States, and a reconstituted ISIS would likely have the requisite assets to inspire or direct attacks against the West. ISIS currently launches and plans attacks from sanctuaries free from counter-ISIS actions, though these are mostly in rural areas with low populations.[6] A US withdrawal would permit ISIS to coerce populations to induce support in some urban or semi-urban areas where the group would have access to greater financial and military assets it could use to plan major attacks. ISIS currently lacks the ability to completely deny the SDF or US access to their sanctuaries, especially in urban or semi-urban areas. A US withdrawal would cause the SDF to lose the capabilities that help it penetrate these ISIS sanctuaries. A robust ISIS insurgency with control over populations and effective military planning structures in Syria would almost certainly aim to destabilize Iraq, which would threaten the stability of the region writ large.

A US withdrawal would also empower US adversaries in the region. Iran would further entrench itself in Iraq and Syria, as it did in Syria beginning in 2011. Iran would have no choice but to address the threat from ISIS by deploying proxies or military forces. Iran used its ground forces to roll back ISIS’s gains beginning in 2015. Iran has used similar deployments and cultivation of proxies in Iraq and Syria to expand its influence. These Iran-backed proxies target US personnel, interests, and allies in the region.

A destabilized Middle East with a reconstituted ISIS with external attack capabilities would impose a trade-off for policymakers between resources devoted to great-power competition versus counter-ISIS operations. The US government would be forced to make a choice between securing the homeland, its allies, and partners against threats emanating from a destabilized Middle East and successfully countering Russia and China. The United States could be forced to slow its “pivot” to Asia again by being forced to increase resources to US Central Command. The current US mission in Syria is a bulwark against the worst-case scenario of an ISIS resurgence at a low cost to the United States without significant risk to higher priority missions.

[1] Source for ISIS claim available on request.

[2] Source for ISIS claim available on request.

[3] Haroro J. Ingram, Craig Whiteside, and Charlie Winter, The ISIS Reader: Milestone Texts of the Islamic State Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 107–49.

[4] Source for ISIS claim available on request.

[5] Source for ISIS claims available on request.

[6] Author’s research.