Africa File

The Africa File is an analysis and assessment of the Salafi-jihadi movement in Africa and related security and political dynamics.

Africa File: US Special Operations Command Africa commander emphasizes ‘strategic’ aims of al Qaeda in West Africa

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk (*) for the reader's awareness.]

The American Enterprise Institute hosted Maj. Gen. Dagvin Anderson, the commander of US Special Operations Command Africa, and a panel of experts on September 9. Maj. Gen. Anderson discussed the status of violent extremist organizations in Africa, including al Qaeda and the Islamic State. He identified al Shabaab in Somalia as the “most imminent” terrorist threat on the continent but framed West African Salafi-jihadi groups as the “deeper strategic concern,” underscoring al Qaeda–linked militants efforts to enmesh themselves in the Sahel region’s “social fabric” and expand into littoral West African states.

Watch the video here.

Read the transcript here.

In this Africa File:

Ethiopia. High tensions between Ethiopia’s federal government and a key regional state are causing political dysfunction and increasing the risk of insurgency or civil war.

Mozambique. Security force abuses will strengthen the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in northern Mozambique.

Libya. The Libya conflict is entering an uncertain phase that will further fragment the country. Russia is attempting to leverage mercenaries’ control of oil infrastructure to bolster its partners’ positions in Libya.

West Africa. Salafi-jihadi groups are expanding their attack zones and deepening their penetration of local governance structures in the Sahel region.

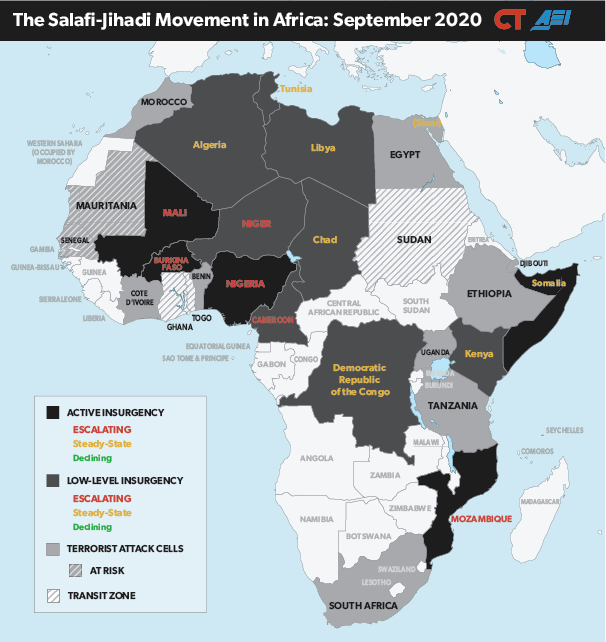

Figure 1. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa: September 2020

Source: Author.

Read Further On:

At a Glance: The Salafi-jihadi threat in Africa

Updated September 17, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic will hasten the reduction of global counterterrorism efforts, which had already been rapidly receding as the US shifted its strategic focus to competition with China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. This reduction will almost certainly include Africa. The US Department of Defense is considering a significant drawdown of US forces engaged in counterterrorism missions on the continent.

This drawdown is happening as the Salafi-jihadi movement, including al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates and allies, continues to make gains in Africa, including in areas where previous counterterrorism efforts had significantly reduced Salafi-jihadi groups’ capabilities. The movement was already positioned to take advantage of the expected general reduction in counterterrorism pressure before the pandemic hit. Now, an increasingly likely wave of instability and government legitimacy crises will create more opportunities for Salafi-jihadi groups to establish new support zones, consolidate old ones, increase attack capabilities, and expand to new areas of operations.

The Salafi-jihadi movement is on the offensive in Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali, where al Qaeda–linked militants are insinuating themselves into local governance while the Malian government is preoccupied with the aftermath of a coup. An Islamic State–linked insurgency has also developed rapidly in northern Mozambique. Salafi-jihadi insurgencies are also stalemated in Somalia and Nigeria and persisting amid the war in Libya. Conditions in these last three countries favor the Salafi-jihadi movement rather than its opponents in the coming year.

Libya’s civil war, reignited on a large scale in April 2019, will continue to fuel the conditions of a Salafi-jihadi comeback, particularly as foreign actors prolong and heighten the conflict. Counterterrorism efforts in Somalia and Mali rest on the continued efforts of international coalitions, support for which is eroding in both host and troop-contributing countries and on local partners that have demonstrated their inability to govern effectively or establish legitimacy in their people’s eyes. Mali’s coup and its aftermath will also disrupt international and regional counterterrorism efforts and coordination.

Amid these conditions, US Africa Command is shifting its prioritization from the counterterrorism mission to great-power competition, a move also intended to reduce risk after a 2017 attack killed four servicemen in Niger. US and European powers aim to turn over counterterrorism responsibilities to regional forces of limited effectiveness—such as the G5 Sahel, which is plagued by funding issues, and the African Union Mission in Somalia, which is beginning a scheduled drawdown.

The Salafi-jihadi movement has several main centers of activity in Africa: Mali and its environs, the Lake Chad Basin, the Horn of Africa, Libya, and now northern Mozambique. These epicenters are networked, allowing recruits, funding, and expertise to flow among them. The rise of the Salafi-jihadi movement in these and any other places is tied to the circumstances of Sunni Muslim populations. The movement takes root when Salafi-jihadi groups can forge ties to vulnerable populations facing existential crises such as civil war, communal violence, or state neglect or abuse (all now likely to be exacerbated by the pandemic). Local crises are the incubators for the Salafi-jihadi movement and can become the basis for future attacks against the US and its allies.

East Africa

Ethiopia

Growing tensions between Ethiopia’s federal government and the Tigray regional state administration may lead to an internal military intervention, increasing the risk of civil war in the East African powerhouse. The Tigray administration *held regional elections in early September in a direct challenge to Prime Minister Ahmed Abiy’s decision to delay all elections until 2021 due to COVID-19. The Tigray administration’s unilateral defiance of Abiy’s order was unprecedented.

The victorious Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the region’s dominant political party, was part of a minoritarian coalition that ruled Ethiopia for three decades before Abiy’s appointment in 2018. It has since *refused to join Abiy’s centralized party. Ethiopia’s attorney general *even accused the TPLF of orchestrating an assassination attempt on Abiy in June 2018.

A former Ethiopian military general called for military intervention in response to Tigray’s regional elections, but Abiy said he would not take such action. A federal intervention in Tigray region could lead to an insurgency or civil war. The Tigray regional state’s growing tensions with Abiy’s administration also threaten unrest beyond Ethiopia by hampering the implementation of the 2018 Ethiopia-Eritrea peace deal.

The destabilization of Ethiopia would create opportunities for the expansion of al Shabaab and the Islamic State in neighboring Somalia, which plotted attacks targeting Ethiopia in 2019. Abiy’s reform program has inadvertently fueled long-standing ethnic fissures, creating opportunities for Salafi-jihadists to exploit local grievances. Al Shabaab released anti-Ethiopian propaganda urging attacks on Ethiopian forces in August.[1]

Mozambique

Security force abuses will likely strengthen the insurgency in northern Mozambique. Amnesty International has reported on alleged torture and extrajudicial execution conducted by Mozambican security forces in September. Abuses have continued despite the Mozambican president’s recognition of human rights abuses during counterinsurgency operations earlier this year. Such abuses will push local populations to tolerate or support the Salafi-jihadi insurgency despite its brutality. Salafi-jihadi militants aligned with the Islamic State captured a port in northern Mozambique on August 12.

Forecast: A Mozambican offensive, likely supported by regional states, will drive the militants out of Mocímboa da Praia port temporarily. The militants will likely choose to retreat. Abuses committed against civilians during operations may strengthen the insurgency. Militants will likely capture the port again after government security efforts have waned. (As of September 17, 2020.)

North Africa

Libya

The Libya conflict is entering an uncertain phase that will likely increase the fragmentation of Libya’s political and security scene. The immediate risk of state-on-state conflict has decreased, with the Turkish foreign minister announcing that negotiations between Turkey and Russia—which back rival Libyan factions—are progressing toward an agreement. Egypt has backed off of earlier threats to intervene in Libya, enabled by the deployment of Russian mercenaries to deter a Turkish-back advance and hold hostage Libya’s oil infrastructure. Talks between rival Libyan parties are ongoing in multiple locations, and the UN secretary-general will soon appoint a new special envoy to Libya after the UN Security Council resolved a deadlock on the issue.

However, these near-term negotiations belie the deep divisions between external and Libyan players over the future of Libya’s government. The UAE and Russia continue to violate the UN arms embargo by providing military aid, including Russian military aircraft involved in combat missions. Turkey and Qatar are investing in long-term influence in western Libya by supporting the development of a military force for the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA), based in Tripoli. Meanwhile, the Libya conflict is contributing to rising tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean, with the UAE conducting military exercises with Greece in a signal to shared rival Turkey.

Russia is attempting to broker a favorable deal in Libya enabled by the Wagner Group’s presence at Libyan oil infrastructure. The presence of Russian mercenaries has bolstered Libyan National Army (LNA) commander Khalifa Haftar even as his coalition has weakened following his retreat from Tripoli in May. Haftar’s forces have blockaded much of Libya’s oil throughout 2020. Russian officials appear to have brokered a deal to reopen oil exports in a meeting attended by one of Haftar’s sons and GNA Deputy Prime Minister Ahmed Maiteeg in Sochi, Russia. This deal undercuts US and UN efforts to end the oil blockade. Libya’s National Oil Corporation condemned the parallel talks in Russia and called for the Wagner Group to leave oil sites before production could resume.

The contentious oil negotiations are contributing to political turmoil that is reshaping power structures in both eastern and western Libya. In the west, Maiteeg’s independent involvement in the Sochi talks may be one factor in GNA Prime Minister Fayez al Serraj’s announcement that he will resign by the end of October 2020. Serraj’s resignation follows popular protests against poor governance in Tripoli, which GNA-recognized militias violently suppressed. Serraj attempted to suspend GNA Interior Minister Fathi Bashagha in response to the protests and crackdown but soon *yielded to pressure—including from militias aligned with Bashagha—to reinstate him. Shifting power dynamics in Tripoli will likely lead to grappling among rival militia blocs for control of the city.

Meanwhile, eastern Libya’s power balance is undergoing a similarly seismic shift. Haftar’s LNA remains a spoiler capable of *rejecting GNA-proposed agreements and has continued to build up military capability in central Libya alongside Russian mercenaries and materiel. The LNA has lost credibility with its foreign backers and local allies since retreating from Tripoli, however. House of Representatives Speaker Ageela Saleh has become increasingly influential and is drawing on a support base that has been a part of the LNA’s loose coalition.

Planned municipal *elections across the east may also signal the declining influence of LNA leadership, which had exercised some of its authority through military governors. Protests, which had been rare under the LNA’s control, have flared in Benghazi and other eastern cities in the last month. The ministers of eastern Libya’s parallel administration resigned on September 12 following protests and subsequent crackdowns by LNA forces.

International Salafi-jihadi militants remain active in Libya. The LNA reported a *raid on an Islamic State cell in Sebha in southwestern Libya on September 15. Some militants were reportedly *carrying Saudi Arabian and Australian identification documents.

Forecast: Fragmentation will increase in both eastern and western Libya, likely leading to internecine fighting among militias. External players will remain involved and will attempt to shape outcomes by backing Libyan political players and armed groups. This fragmentation may produce the appearance of political progress at a national level as various factions attempt to capture legitimacy by positioning themselves as dealmakers. However, local instability will undermine opportunities for national reconciliation.

Continued and worsening fragmentation in Libya preserves and worsens the conditions that allow Salafi-jihadi groups to strengthen. The Islamic State will likely continue its renewed attack tempo and may resume intermittent attacks targeting symbolic state institutions in coastal cities in the coming months, possibly to stoke tensions and prolong political dysfunction. (Updated September 17, 2020)

West Africa

Salafi-jihadi groups are expanding their areas of operations in the Sahel region. This expansion is not a direct result of Mali’s political turmoil following the August 18 coup, but the ability of Salafi-jihadi groups to both expand their attack zones and deepen their de facto control of vulnerable communities will increase if local and international counterterrorism efforts are disrupted.

The Islamic State claimed responsibility for executing six French aid workers and two Nigerien citizens in a wildlife preserve previously considered safe for tourists near Niger’s capital. The claim, released in the Islamic State’s weekly periodical al Naba on September 17, framed the August 9 executions as a blow against the French security operation in the Sahel. It emphasized the nearness to Niamey, Niger’s capital, and the threat to tourism in the region.[2]

The attack is not the first by Islamic State–affiliated fighters near Niamey but signals an eastward shift away from the Malian border. The targeting of civilians in Niger is also an inflection. The Islamic State conducted several devastating attacks on Nigerien security forces in the past year. The same group is responsible for the 2017 attack that killed four US servicemembers in western Niger and other subsequent attempted attacks on US forces in Niger.

[Note: The group commonly known as “the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara” conducted this attack. The Islamic State refers to both this group and a separate affiliate in the Lake Chad Basin as “West Africa Province.”]

The August 9 attack in Niger demonstrates militants’ continued infiltration of wildlife parks. Militants affiliated with both the Islamic State and al Qaeda have begun establishing permanent bases in the wildlife park that connects Niger, Burkina Faso, and Benin. Gunmen kidnapped two French tourists and killed their guard in Benin in 2019.

The August 9 attack also demonstrates the Islamic State’s West African affiliates’ increased focus on executing aid workers and disseminating gruesome propaganda. The Islamic State affiliate in the Lake Chad Basin has taken an increasingly brutal approach toward targeting civilians, including aid workers, this year.

Militant activity also expanding southward along the Malian-Burkinabe border. A land mine *struck an ambulance, killing several civilians, in Sikasso, Mali, near the Burkina Faso border on September 11. Attacks are rare in this area, which falls south of the militants’ usual area of operations.

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s affiliate in Mali is embedding itself more deeply in local governance. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) has begun to mediate between rival ethnic groups in central Mali.

Forecast: The Islamic State in the Sahel will draw greater counterterrorism pressure because of its high-profile attacks in the region. JNIM will benefit from reduced counterterrorism pressure and the Malian political crisis that will likely draw security forces toward Bamako. JNIM will continue to embed itself in northern and central Malian communities and will likely begin to quietly establish governing institutions—such as courts—in the coming year. (Updated September 17, 2020)

[1] “Shabaab Explores History of Somalia-Ethiopia Conflict in Part 1 of Video Documentary,” SITE Intelligence Group, August 3, 2020, translation available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com; and “Shabaab Highlights Attacks on Ethiopian Forces, including January 2019 Ambush, in 2nd Part of Video Documentary,” SITE Intelligence Group, August 18, 2020, translation available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.

[2] “IS Takes Credit for Execution Of 6 French Aid Workers at the Kouré Giraffe Reserve in Niger,” SITE Intelligence Group, September 17, 2020, translation available by subscription at www.siteintelgroup.com.