{{currentView.title}}

January 22, 2014

Putin's Olympic Gamble

In Russian President Vladimir Putin’s New Year’s address, he promised to keep up the fight against terrorists in Russia’s North Caucasus until “their complete destruction.” With the Sochi Winter Olympics less than a month away, however, it is becoming increasingly evident that Putin has bitten off more than he can chew.

For the Russian leader, the terrorist threat emanating from the North Caucasus is especially troubling because he has staked his reputation and Russia’s prestige on the Olympics going off without a hitch. Putin has always fancied his leadership (and iron fist) a panacea for violence and destabilization in the North Caucasus. During his first presidential campaign in 2000, Putin ran on a tough-on-militants platform in the midst of the Second Chechen War (and spent the turn of the millennium in Chechnya personally awarding Russian troops hunting knives for their efforts). In 2009, Putin went so far as to declare that the counterterrorist operation in the North Caucasus was over. Not quite.

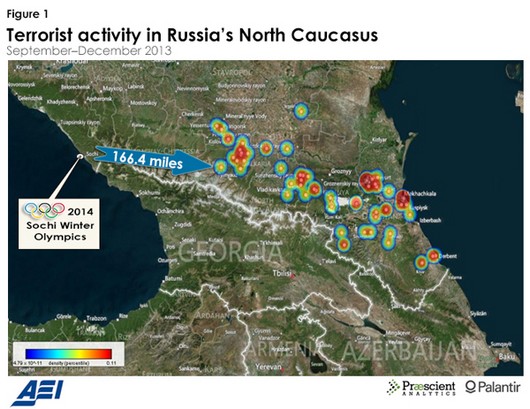

Terrorist-related violence in the restive region continues to this day, most prominently in the republics of Dagestan and Kabardino-Balkaria, which respectively saw 81 (57 successful) and 22 attacks (16 successful) between September and December 2013. Shootouts with policemen and security forces are a regular occurrence. Weapons caches filled with ammunition, grenades, and the rare suicide belt are discovered almost weekly throughout the region. Explosions target law enforcement, security infrastructure, and the occasional store selling liquor. [1] Clearly, the insurgency still rages (see Figure 1).

The terrorist threat in Sochi’s backyard

A radicalized Islamic movement aiming to establish an Islamic state in the region emerged from a separatist campaign in Russia’s North Caucasus. Doku Umarov, the self-declared Emir of the North Caucasian mujahideen, founded the Islamic Emirate of the Caucasus (IEC) in 2007. The US State Department designated the IEC as an international terrorist organization in 2011. Umarov continues, at least nominally, to lead (unless recent, unverified rumors of his death prove true) this decentralized umbrella organization, which encompasses a number of small militant cells fighting throughout the North Caucasus.

Putin proposed Sochi as the site for the 2014 Winter Olympics fully aware that a winning bid would position the Games on the border of Umarov’s self-proclaimed Islamic state. In July 2012, the IEC commander responded. Umarov threatened, "They plan to hold the Olympics on the bones of our ancestors, on the bones of many, many dead Muslims buried on our land by the Black Sea. We as mujahideen are required not to allow that, using any methods that Allah allows us.”

Can the IEC make good on Umarov's threat? Previous IEC attacks have occurred as far away as Moscow (including the 2010 Moscow Metro and 2011 Domodedovo Airport suicide bombings) and serve as troubling reminders that the IEC does have the capacity to strike targets outside the North Caucasus (see Figure 2). For example, back-to-back bombings last month in Volgograd (a major transit hub that connects the North Caucasus and Sochi to the rest of Russia) on December 29 and 30, 2013, killed nearly three dozen people. If the Olympics prove too hard of a target, the IEC may aim to attack less secure Russian cities outside of Sochi’s security zone, dubbed the “ring of steel.”

Are Russian security forces prepared?

The security apparatus Putin has installed to protect Sochi during the Olympics includes tens of thousands of Russian security personnel, numerous drones, more than five thousand cameras, six short-range air defense systems, and some submarines. And since the twin bombings in Volgograd, Putin and his hand-picked officials in the North Caucasus have doubled down.

In an antiterrorist sweep immediately following the attacks in Volgograd, 700 people were detained. Putin signed a law that would punish "public appeals for separatism" with up to five years in prison. Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, who fought alongside the Russian military during the Second Chechen War and was personally selected by Putin as the Republic’s president in 2007, ominously warned, “I strongly believe that we will not root out this evil by playing democracy and humanity games.” Ramazan Abdulatipov, the head of Dagestan, announced his intent to expand control over terrorists’ kin and to mobilize the population against the terrorists (800 Cossacks, a people descending from the infamous cavalry who served to protect the Russian tsarist empire, have already reportedly volunteered to help patrol the Olympics).

Heavy-handed tactics, however, may not be enough to keep all of Russia safe during the Olympics next month. Rather than attacking other serious challenges in the North Caucasus that are winning the terrorists some sympathy among the locals — like unemployment, egregious human rights abuses, and a complete lack of political representation for the North Caucasian population — these measures appear to be solely directed at appeasing a nervous populace.

In hand-picking Sochi for the Olympic bid, Vladimir Putin made the assumption (with his usual bravado) that he could manage the full-fledged insurgency waging in Sochi’s backyard. On Sunday, he boasted that Russia's security services have a “perfect understanding” of the terrorist threat to the Games and knew “how to stop it” and “how to combat it.” That may turn out to have been a grave miscalculation.