{{currentView.title}}

December 18, 2018

More Chants, More Protests: The Dey Iranian Anti-Regime Protests

[Notice: The Critical Threats Project frequently cites sources from foreign domains. All such links are identified with an asterisk(*) for the reader's awareness.]

The widespread anti-regime Dey Protests in Iran (December 2017 – January 2018) were the largest demonstrations since the 2009 Green Revolution that followed the fraudulent re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Dey Protests were fundamentally different from the 2009 Green Movement, however. Dey lacked organization and leadership, was unequivocally anti-regime, and attacked Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the principles of clerical government explicitly and sometimes nastily. The Dey Protests also drew on a much wider demographic than the Green Movement. Dey protesters came from largely rural areas and smaller cities in relatively poor areas. Protests in 2009 were comprised of Tehranis and urbanites. Whereas the 2009 protests sought reformation of the regime’s policies,

Iranians took to the streets on December 28, 2017 in northeastern Iran to protest the government’s mishandling of the Iranian economy. The chants in these first protests overwhelmingly targeted President Hassan Rouhani and his government, rather than the Supreme Leader or other elements of the Islamic Republic regime. Some reformist media sites *claimed early on that hardliner elements in Mashhad organized the first protests there to attack Rouhani over recent economic issues. Mashhad-based hardline cleric Ayatollah Ahmad Alam ol Hoda, a staunch supporter of Ebrahim Raisi, the conservative whom Rouhani defeated in the 2017 presidential election, *denied the claims.

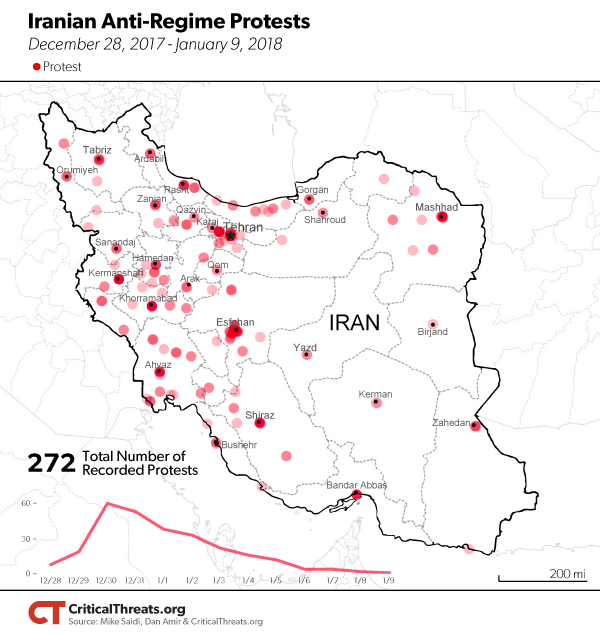

Protesters in Mashhad soon moved beyond attacking the Rouhani administration to target the very foundations of the Islamic Republic, however, which Alam ol Hoda could certainly not have desired. The now anti-regime protests in Mashhad soon encountered stiff resistance from regime security forces. But the protests not only did not stop, but rather spread. Anti-regime protests moved westward to Kermanshah Province on the border with Iraq and soon engulfed all of Iran’s 31 provinces. Nearly 100 cities saw anti-regime protests before the demonstrations died out in early January 2018.

Protesters called for the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and accused regime leadership of plundering the nation’s wealth to support Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon. Regime security forces contained the protests with relative ease. Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) anti-riot and local Basij units generally controlled them without the violence and killing seen in the suppression of the 2009 Green Movement. Protesters in smaller cities were able to overwhelm local police and security forces in some cases, requiring the deployment of elements of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and the Basij militia on a limited scale.

Protesters often attacked key revolutionary principles such as velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist—the key ideological justification for Khamenei’s rule). Protests also denounced clerical leadership and renounced the 1979 Islamic Revolution that brought the current regime to power. Western coverage of the protests in Iran noted the prevalence of chants praising the Pahlavi dynasty that the revolution had overthrown and calling for the return of the Shah. We will consider these pro-Shah chants in more detail presently.

The explicitly anti-regime, anti-Supreme Leader, anti-clerical government, and pro-Shah chants made the Dey Protests a much more serious ideological challenge to the regime than the Green Movement ever was. The depth and breadth of popular resentment manifested in these protests should also have concerned the regime deeply. The protest movement has continued since Dey, moreover, albeit in interestingly altered forms, as the Critical Threats Project has reported. It shows no signs of going away. The Islamic Republic has entered uncharted waters in the face of this widespread but still relatively disorganized and seemingly leaderless opposition. Its survival is not yet threatened, but the foundations of its popular support may be crumbling.

Methodology

The Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute has reviewed over 2,500 videos from social media, primarily Telegram and Instagram, capturing the Dey Protests in late December 2017-early January 2018. We developed a comprehensive list of slogans and chants commonly used during the protests. We have estimated the approximate sizes of the protests and the exact locations of several protest sites. Our dataset also includes details on protester and regime security forces’ behavior. The discussion below is drawn from this robust dataset of the more than 270 individually-assessed protest events from Dey.

The dataset is incomplete—videos covered only portions of each protest and not all protests had videos posted. Protesters and their external supporters often reposted videos to claim that they were of new protests. The CTP team has worked diligently to eliminate these duplicates and to validate that the videos we used reflected actual protests on the dates and at the locations to which we assigned them, but some errors likely remain. CTP is confident that this dataset contains a comprehensive list of significant protests and the major chants used throughout this movement, however. Low-confidence assessments of protest sites in the dataset are marked with an asterisk.

Iranians submitted videos of the protests to many social media channels. Protesters often posted videos in which they clearly stated the time, date, and location of the protests. By no means do all videos contain such information, however. CTP assessments of date and location rely heavily on video captions and available metadata. Our team worked diligently to assess exact locations and dates for when the protests happened during Dey by looking for key landmarks and other telltales.

Openly anti-regime groups such as the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) muddied the waters by reposting older videos with different times and locations, exaggerating the spread and sometimes distorting the character of the protests. Our team carefully analyzed the videos for inconsistencies to counter these distortions.

View and explore our full data set at the end of this article.

Hardliners Likely Started anti-Rouhani Protests that Got Out of Hand

Initial reports claimed that Mashhad-based Supreme Leader Representative for Khorasan Razavi Province, Ayatollah Ahmad Alam ol Hoda, organized the first Mashhad protests to focus popular anger against Rouhani. Chant patterns support these claims.

Demonstrations on the first day, in Mashhad and Birjand (South Khorasan Province), both contained anti-Rouhani chants. Alam ol Hoda is a regime insider and father-in-law of failed presidential candidate Hojjat ol Eslam Ebrahim Raisi. Raisi lost to Rouhani in the 2017 Presidential elections. Raisi is also the head of the Mashhad-based Astan Quds Razavi, an economic giant that dominates the eastern Iranian economy and is responsible for the Imam Reza Shrine in Mashhad. Both Raisi and Alam ol Hoda maintain large patronage and support zones throughout eastern Iran. Both Mashhad and Birjand have historically been strongholds for hardliners in presidential, parliamentary, and Assembly of Experts elections—Raisi’s Assembly of Experts seat represents Birjand, which is likely his most significant power base outside of Mashhad. Raisi and Alam ol Hoda likely mobilized hundreds of their followers to stage anti-Rouhani protests in Mashhad and Birjand on December 28.

Alam ol Hoda’s plan quickly backfired, however, as his attempt to stage a local anti-Rouhani protest got away from him. Protesters soon turned their ire away, or rather, beyond Rouhani and toward the regime and all of Iran’s clerical leadership.

Pro-monarchical chants resonated in larger cities with a sizable bazaari class

The Dey Protests included a noteworthy number of pro-Shah slogans and chants. Common chants included “Reza Shah, may your spirit live on!” and “Oh Shah of Iran, please return to Iran.” Pro-Shah slogans are in many respects more threatening to the regime even than chants calling for the death of the Supreme Leader. Pro-Shah chants not only demand the end of the Islamic Republic of Iran but they also identify a potential replacement government to the current regime. CTP does not assess that the current head of the Pahlavi dynasty would receive widespread popular support were he to attempt to regain his throne in Tehran, but the identification of a possible replacement to the current ruler and government of Iran is a significant departure from previous protest movements.

Pro-Shah slogans appeared in cities of more than 300,000 people, cities that would presumably have a sizeable and influential merchant class. Iran’s merchant class, commonly referred to as bazaaris, helped usher in the Islamic Revolution in 1979, supporting late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in protest of the Shah’s economic policies.

The smallest city to produce pro-Shah slogans was Kashan in Esfahan Province. Larger cities such as Tehran, Mashhad, Qom, and Shiraz also saw many instances of pro-Shah sloganeering. Ironically, the cities of Mashhad and Qom, which are regime support zones, were the first to see pro-Shah slogans.

Regime officials predictably accused foreign governments and monarchists of organizing the Dey Protests. Our analysis indicates that this was not the case. The patterns of chants strongly suggest a spontaneous evolution of protests initiated by Raisi’s allies but offer no indication that foreign actors controlled or co-opted the demonstrations over time. Among other things, any such cooptation should have been observable in the introduction of new slogans over the course of the protest movement as outsiders worked to inject their preferred messages once the movement began. The chants, on the contrary, reduced in variety with no new slogans appearing after the first couple of days, settling on much more general anti-regime and anti-Supreme Leader messages by the end of the demonstrations.

The regime’s attempt to blame the protests on outside organizers follows its usual pattern of explaining any activity against it. It also suggests that the regime pays close attention to the speeches of Reza Pahlavi, however. The regime certainly considers monarchists a threat and likely perceived widespread pro-Shah sloganeering worrisome.

Pahlavi gave an interview to Manoto TV, a UK-based Persian-language television channel available on satellite, on January 3, 2018. Many Iranians follow Manoto and its programming. Pahlavi called for the Iranian armed forces, namely the IRGC and Artesh, to choose a side and to support the people in the face of government suppression.

This interview appears to have had no effect on the protests. Pro-Shah chants ended after January 2, according to our data. Protesters throughout the demonstrations, moreover, called for the Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) and occasionally the Artesh to join them, but such calls did not increase or change after the his interview. We have found no instances of protesters calling on the IRGC to support them. The impact of Pahlavi’s interview might have been mitigated by the regime’s *blocking of Instagram and Telegram on December 31, 2017, although protesters likely could still have heard it on the satellite station. This pattern of activity suggests that the protesters may have been more focused on the Shah as a symbol than as a real and viable replacement for the current leadership. It certainly undermines any notion that monarchists played a significant role in organizing the demonstrations or co-opting them.

Iran First

The single instance of an anti-Russia chant during the protests is noteworthy. Citizens of Hamedan chanted “Death to Russia” on December 29, 2017. Hamedan is home to Artesh Air Force’s Shahid Nojeh Air Base. The air base gained notoriety when Russia began air operations in Syria during the Fall of 2015. Russian combat aircraft were parked at Shahid Nojeh in November 2015.

Iranians are traditionally ardent opponents of colonialism and colonialist powers. The Iranian Constitution, in fact, prohibits the regime from allowing foreign powers to occupy or operate from Iranian territory. Regime officials, including the Supreme Leader, oftentimes make explicit and allegorical references to Iran’s role in defending against colonial powers. These references focus on Britain and the U.S.—but Russia occupied portions of Iranian territory under both the tsars and the Soviets. Iranian officials nevertheless permitted Russia to use the Hamedan air base for Russian air operations in eastern Syria, sparking a public controversy. Russian overt use of the airbase quickly ended. Rumored discussions between Russian and Iranian officials, including the head of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) Ali Shamkhani, over future Russian use of the base were ongoing as of Spring 2018.

The appearance of anti-Russian chants in Hamedan manifests public, not just elite political, disapproval of their government’s support and assistance to a foreign power. It is of a pattern with other popular slogans aimed at the regime’s expensive and unnecessary regional escapades, such as “Forget about Syria, think about our condition!” Many Iranians disapprove of the regime’s involvement in the Syrian Civil War. The anti-Russia chants likely denote unhappiness at the regime’s material support of a foreign power and assistance to a foreign power in order to support to a venture, like the Syrian Civil War, that many consider to be a waste of Iran’s precious and limited resources. The ubiquity of anti-Syria chants supports this assessment.

Chants opposing the regime’s regional adventurism and financial backing of non-Iranians were among the most common during the Dey Protests. The provinces with the *highest unemployment rates (West Azerbaijan, Khuzestan, Sistan va Baluchistan, Kohgiluyeh va Boyer Ahmad, and Kermanshah) saw extensive sloganeering complaining of the regime’s regional behavior.

Anti-corruption Chants Prevalent among Unemployed Populations

Protesters’ use of chants targeting the regime’s corruption and economic mismanagement revealed interesting patterns. Ethnic minorities in Khoy, Rasht, Ilam, Kermanshah, Abadan, and Zahedan used chants such as “if one embezzlement ends, then our problem will be solved.” Protesters also accused the government for supporting “the house of thieves” that Iran has become. Cities and areas along Iran’s border regions participated in these chants. Iran’s perimeter is chiefly inhabited by ethnic minorities such as Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, and Sunni Baloch. Additionally, the four provinces with the highest unemployment rates—Kermanshah, West Azerbaijan, Sistan va Baluchistan, and Khuzestan—all saw the extensive use of such chants. The participation of ethnic minorities, who are among the country’s most economically marginalized citizens, supports the notion that Iranian ethnic minorities hold longstanding and deep-seated resentments of regime officials and of regime corruption. The prevalence of anti-corruption and anti-regional chants among the provinces with the highest jobless rates denotes that those most affected by the regime’s bad economic policies may have been the ones who championed those chants.

These patterns should concern regime leaders for several reasons. First, they demonstrated that minority resentment extends beyond the well-known Balochi disaffection and even beyond the anger that Iran’s Arab minority has since displayed in Khuzestan Province. Localist chants by Azeris in Tabriz and Gilakis in Rasht suggest that ethnicism extends, at least in a limited way, even into minority populations thought to have been thoroughly integrated into the Islamic Republic—Khamenei himself, after all, is part Azeri.

Anti-corruption chants in poverty-stricken regions are unsurprising, secondly, but problematic for the regime. Iranian protests have historically been concentrated among wealthy urbanites and university students. Poor workers have not usually participated in them on a large scale. If resentment among such people has risen to the level of bringing them into the streets, the regime must consider the danger over the long term of a truly broad-based opposition.

These protests by the poor likely reflected specific anger over Rouhani’s *attempts to roll back the dramatic expansion of government subsidies that his predecessor, Ahmadinejad, used to cement his own power base. Those subsidies represent an unbearable drain on the Iranian treasury, particularly in the face of re-imposed U.S. sanctions. Reducing them has been a Rouhani priority since taking office, and is essential to balancing the state budget. These protests did, in fact, delay subsidy reform and may make it impossible.

Conclusion

The Dey Protests spurred a new, vibrant protest scene in Iran. Protests over labor problems, ecological issues, ethnic and religious issues, and political machinations resulted in violent protests throughout Iran since Dey. A renewal of explicitly anti-regime protests has not yet occurred, however.

The regime is highly unlikely to address the root causes of the protests or redress the grievances that drive them. The regime has failed to institute the necessary economic reforms to reduce unemployment and to bring in much-needed financial flows into Iran. Added economic pressure following the reimposition of U.S. sanctions against Iran in November 2018 has worsened the economic crisis in Iran. The Iranian economy continues to underperform and the Iranian rial has devalued by 300 percent against the U.S. dollar since last year.

Protests in Iran will undoubtedly continue to occur and evolve. They have not challenged the regime’s survival, however, and are unlikely to pose an existential threat to the regime’s security any time soon. It is unclear when the next round of widespread anti-regime protests will take place in Iran. The anniversary date of the Dey Protests is soon approaching. Will Iranian protesters take to the streets once again? We will soon see.

View and explore our full data set below.